When the Pen is Mightier Than the Casting Couch

Every time I sit down to write a play, I create a job.

With a stroke of my pen, I can employ people of every gender, size, shape, orientation, ethnicity, and ability. Produce the play once: I’ve created several jobs. Produce the play again: more people are employed.

And if I write a play that lasts, with universal themes that resonate four hundred years after my death, I may employ thousands of artists—actors, directors, stage managers, producers, and ushers, too. Just like a certain lad from Stratford-upon-Avon has consistently employed me, although I never met him.

Every time I sit down to write, I shape my entire industry.

It wasn’t enough to get the jobs that existed—those demure and responsive women. No. I wanted the jobs as good as Hamlet.

A World of Pure Imagination

It is perhaps not common to think of a role a playwright writes as a job for someone else. As storytellers, we tend to focus first on the play at hand, without always thinking of the practicalities that accompany our story. Yet, this is exactly what we must do.

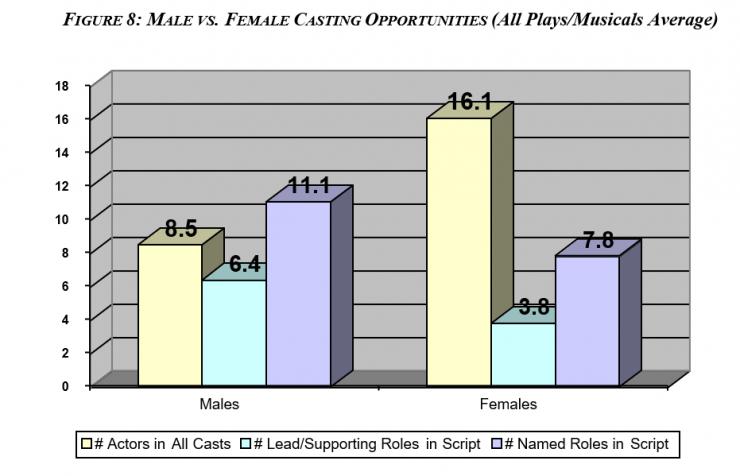

Playwrights have been gifted the proverbial purple crayon, and while perhaps it requires a producer’s money to bring the drawing fully to life, the producer, the director, the actors, and everyone are dependent upon what the playwright creates. If a playwright writes Treasure Island for twenty white men, then twenty and forty and a thousand white men have a job for decades to come, leaving everyone who isn’t a white man literally without employment. I may as a woman train for years and years, tune my instrument to be the best that it can be, and yet—because I will never be a man—I will never, ever get that job. I needn’t even apply.

Because one of the curious things about theatrical employment for actors is that—unlike, say, an office job, where certain skills are more important than outward appearances—outward appearances can absolutely remain a job requirement. Without a director’s extreme intervention, Falstaff cannot be skinny; Othello cannot be white; Helena must be taller than Hermia; and Lear should always play as aged. Gender, ethnicity, orientation, age, shape, ability—everything that makes you “you” can be dictated by the playwright. And for a living playwright, he may even exert greater control over who may be hired, such as Samuel Beckett’s estate disapproving of female inclusion in a production of Waiting for Godot.

Fortunately, the tide is slowly turning. In “Why Diversity is Not Enough,” Matt DiCinto argues that playwrights should start listing identifiers in character descriptions, if only to show their own ethnic biases, or help producers overcome theirs. In “Body-Shaming: The Epidemic Plaguing Collegiate Theatre Programs,” Rachel Bykowski rightly points out the inherent biases associated with employment of certain silhouettes. Parity Productions, The League of Professional Theatre Women, and many other organizations are working to encourage diversity, equity, or at least parity in theatrical productions.

I should like to argue for even more than that. More than quantity, I should like to argue for quality. I should like to argue for characters worth playing.

Who Am I, Anyway? Am I My Resumé?

Every young actor wants to play the lead. Why? Because it’s generally accepted that the lead is a role worth playing. Yet, when we get down to the roles written expressly—say, for women, we have to wonder whether they’re any good at all.

I remember the last leading role I got, before I was typed as a “woman of size.” It was fifth grade. Really Rosie. Title character. With my Girl Scout Troop. We were terrible, but I had a grand old time.

I developed after that, and began gaining weight. Which meant that I quickly slipped from the star of the show down to Wicked Witch, and Disapproving Mother, and then Comical Fat Man, and then Girl Who Stands In Wings And Sings High E Because Her Soprano Voice Doesn’t Match Her Alto Body—and then…simply not cast at all.

I envied the glittering ingénue, or thought I did. She at least had stage time. She had desirability, which passed for agency. She had good songs.

But was her role really worth playing? She was acted upon more than acting. She was arm candy. She had one job, and it was to Want The Man—who in turn got to do all the swashbuckling and decision-making and speechifying about things other than love.

Over time, I began to realize that there were really only three roles for women: one to get the guy, one to want a guy, and a matron to disapprove. I generally played the matron. If there were any extra roles they tended to be handmaids, crones, and clowns. I played a lot of crones. I played my share of clowns. I’ve also played a lot of men, because there are more spear-carrier roles than there are male spear-carriers. And I was still cast-able: able-bodied, cis, white. I was at least carrying a spear.

I spent several years on the other side of the table after that: teaching, writing, directing. Watching young men flourish with lead role after lead role. Watching promising women wither, because the jobs just do not exist, and that spear gets heavy quick.

When I did return to acting, I was gratified to land some juicy roles: Rosalind, Lady Macbeth, Ophelia. Even so, Rosalind only gets to talk because she’s dressed up as a boy. Lady Macbeth comes on strong and then simply disappears. And poor Ophelia, with so few lines in her own defense. And each woman still defined, and defining herself, by her man. More: I was only getting the role because I was someone’s idea of sexy. Gratifying, certainly—but who cares if Macbeth the man is sexy? We want Hamlet to be intelligent, more than we want a chiseled chin.

I began to wonder what other stories existed for women. No. I began to wonder where were the better jobs? Ophelia may be listed in bright letters next to Hamlet, but the job simply wasn’t as good, as technical, as dexterous. It wasn’t enough to get the jobs that existed—those demure and responsive women. No. I wanted the jobs as good as Hamlet.

So I picked up my pen.

For the playwright, the employer, it means getting to know actors better and purposely widening your circle so that you can write jobs for more than just the three white guys you know...Go to auditions and see not what box the actor is putting herself into, but who she truly is—then write that.

I See Your True Colors

In 2008, I set out to write the first of several purposely-vibrant female characters, in this case the titular heroine of Cupid and Psyche. By 2013, we were in auditions with my theatre company, Turn to Flesh Productions (TTF). In our quest for Psyche, we called in some of the most bad-ass, non-traditional, unapologetic, grounded, loud, opinionated, earthy women we could find. We gave each auditioner a half-hour slot and four scenes, working with our leading actor, who was a generous collaborator.

While the role is romantic, Psyche in fact refuses to define herself by the god of Love. She’s stubborn, she’s funny, she’s intelligent, brash. I expected the actresses to present the same. Imagine my horror, then, as each woman who came into the room immediately became “girlish” as soon as we began to work. They moved with tentative grace. Raised their natural voices half an octave. They demured.

And I realized, even as I coached them to take ownership of the stage, that these accomplished actors were behaving this way because this is what got them the job.

It’s not enough to write the better roles, there is also an adjustment period as those who have never gotten the jobs learn how to relax and tap into those natural parts of themselves in order to fill the roles they have never been allowed to voice. This may require a longer rehearsal period, or perhaps more opportunity to include diverse actors in the development of a play, or both.

Recently, TTF held a “smashing stereotypes” workshop called True As You Can Be as part of the Shakespeare Forum annual festival. In the workshop, actors were given new verse drama scenes that hopefully matched a part of their truest selves, and allowed them to express that self with affirmation on the stage. One of the things we stressed in the workshop was that this was the opportunity not just to try on new roles, but to reveal to playwrights what roles still need to be written. Not: how has this actor failed to live up to this part, but where have our playwrights failed to capture the glorious multifariousness of real people?

For directors, it means casting outside the box—or outside the wardrobe—and then being cognizant that the actor in front of you may need more attention and coaching, since they have not had this job opportunity before. It’s not enough to merely cast diversely: as directors, we must be prepared to receive the stories of pain and hurt that will rise up in actors speaking their truth for the first time. We will need to respect that, and welcome that personal story into the process of theatremaking.

For the playwright, the employer, it means getting to know actors better and purposely widening your circle so that you can write jobs for more than just the three white guys you know. Listen to your actors and ask for their stories in order to write their jobs. Go to auditions and see not what box the actor is putting herself into, but who she truly is—then write that. Go to auditions and see who won’t get the job because they’re too brown, too deaf, too short. Then write a job expressly for them.

Consider, too, what identifiers you use for the actor. As my colleagues have pointed out, in the United States, the default is white and skinny. Try describing your character with other adjectives. Make a point to the director to change your written descriptions to fit the actors, rather than the other way around. If you’re describing a woman, don’t mention how traditionally beautiful she is, unless she’s Helen of Troy—and probably not even then. Why shouldn’t Frances McDormand or Tilda Swinton play Helen? Then, when you’re about to have your usual male protagonist go on the adventure, stop and see what happens if you give someone else the job.

With a stroke of a pen, you employ one, ten, ten thousand people.

Who will you employ today?

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here