Performance and war are intertwined, perhaps more closely than we would like. War is immanently performative, as is the conduct of war. The actions of the military and politicians who wage war are rooted in their desire to demonstrate power and influence the shape of the world.

Lindsey Mantoan writes about this in detail in War as Performance, exploring the theatricality and performativity of war as exemplified by the conflicts in Iraq. Mantoan shows how military operations rely on practices rooted in theatricality, both in combat operations and in the framing of war within the aggressor state. She recounts the American Ghost Army, which distracted and deceived rivals during World War II.

Natalie Alvarez in Immersions in Cultural Difference: Tourism, War, Performance describes mock Afghan villages that were built in California (as well as in Canada and Britain) to train soldiers for real military action. In that setting, full-scale plays rehearsing the war took place. The cruel irony is that the “actors” playing the Afghans were recruited from the Afghan diaspora: these people who had fled the war were asked to play out their usual “pattern of life” for American soldiers—some of the producers of this chaos.

But these books also show that by examining war and the culture of war through the lens of performance studies, one can better understand how to resist this culture. Judith Butler writes, “Visual and discursive fields are part of waging and recruiting support for war.” These fields are shaped by certain performative events: the sublimation of patriotism and fake propaganda. In Russia, where the authorities shy away from announcing a full-fledged mobilization because it threatens Russia’s existence, there have recently appeared mobile contract recruitment stations, next to which an inflatable soldier stands and calls citizens to die for the sake of the insane president.

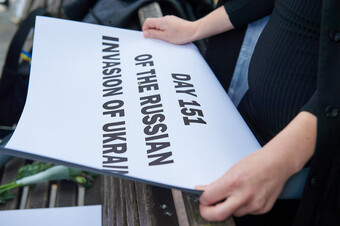

Protest performance (as well as performative/visual art like street art) gives people the language to call a war, a war.

Just as the performative, rhetorical, and visual dimensions of war are drawn to manipulate the feelings and thoughts of the population to secure its support, so too can they be intercepted by citizens, academics, and artists to respond by establishing a mindset in which military solutions to conflict are impossible. Very often, people simply do not have the language to call things by their proper names; in Russia, a huge number of the population is dissolved in a slow death (which, Loren Berlant says, is when living conditions are barely suitable for survival) and has a very low quality of information consumption. Protest performance (as well as performative/visual art like street art) gives people the language to call a war, a war.

War can be transferred not only in space (from there to here) but also in time, from the past to the present. Jessica Nakamura writes about this in Transgenerational Remembrance: Performance and the Asia-Pacific War in Contemporary Japan. She describes how, through theatrical and performative acts, the ghosts of war victims return to Japan's present and how this helps both to heal and to preserve the memory of war crimes—both perpetrated against and by Japan. These processes help shape what the Japanese philosopher Takahashi Tetsuya calls “postwar responsibility” (sengo sekinin)—the responsibility of people born after the war or not guilty of direct warfare. In essence, this is people's responsibility to keep the peace.

Tetsuya talks about the performative actions taking place around Tokyo's Yasukuni Shrine, the official memorial for everyone who “died for Japan and Emperor.” This shrine is a point of multiple controversies; of the 2,466,532 people contained in the shrine's Book of Souls, more than 1,000 were convicted of war crimes. Therefore, in addition to official events, protests took place there, like Koizumi Meiro's Melodrama for Men #5: Voice of a Dead Hero, in which Koizumi dresses as a dead kamikaze pilot, who wanders around the city in search of his fiancé and then staggers back to the shrine.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here