Whose Story to Tell? Akron, Ohio Relates to the Indigenous Amazon

In Death of a Man the New World Performance Lab explores Akron Ohio’s complicated history and relationship with its number one industry: rubber. The show is set at the turn of the century, when the “mad search for natural rubber began” and the booming industry gave Akron it’s infamous nickname “the Rubber City.”

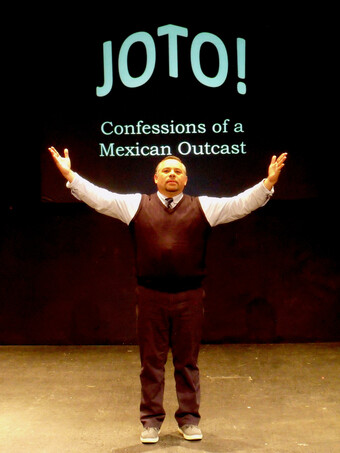

A one man show conceived and performed by long-time Akron resident Jairo Cuesta, Death of a Man, tells the haunting tale of an indigenous man whose people are manipulated, tortured, and destroyed by the western world’s demand for rubber. Director James Slowiak relates that “Death of a Man is an attempt at authentic intercultural understanding by re-engaging the past and bringing it alive in the present.” The piece leaves its audience implicated through revealing the true cost of having four tires on your car. Death of a Man animates this shocking history not to shame or discourage, but to acknowledge the past and promote healing in the “Rubber City.”

Death of a Man is the first installation of New World Performance Lab’s The Devil’s Milk Trilogy, devised in conjunction with the Center for Applied Theatre and Active Culture. I was fortunate enough to see this piece twice, once in workshop during the spring of 2015 and then in full production this past February. Between the workshop and the full production, Jairo and James travelled to the Amazon, where they met with the people of the indigenous community.

In a post-show talk back Jairo and James discussed their experience in the upper Amazon. They were surprised by the collision of modernity and native culture. They spent time speaking with the community, eating native food, and immersing themselves in native culture. Though the tribe “governor” welcomed them, he also questioned their intentions, admonishing that they didn’t have the right to tell this story. James and Jairo were left to wonder: whose story is it to tell? Do we have the right to tell the history of the indigenous Amazon? How can this story belong to Akron, Ohio?

In response to these concerns, Jairo presented the community with a ten-minute clip of his work. He is an expert storyteller with the ability to instantly bring the audience into his given circumstances. While watching Jairo on stage, one is suddenly transported through time and space to the Amazon circa 1909. A classic proscenium stage is turned into an intimate multilevel space. The audience enters into a dimly lit room, fluttering with the soft sounds of the Amazon. A quiet sorrowful chanting is heard as Jairo enters slowly traveling from the upper level stage to the ground floor in a ritualistic walk while gently shaking tree branches in both hands. As his eyes greet his audience, we meet our storyteller. He paints a picture of himself having a torturous death; he remembers the words of his father “a quick death is a good death.” Jairo jumps into the next landscape, “The Man from The Putumayo” as Imbitide, a young man of the Uitoto, the native people of the upper Amazon. His father is the chief of his tribe, he too will be chief someday. A ritual of entering manhood takes place; as he willingly and silently endures a test composed of an elder fastening sugar cane “to my [his] loins for the red ants to collect the sweetness and to sting me [him]”. After surviving the challenge, the prideful tribe celebrates all the boys who are now men. Jairo shares the joy of Imbitide’s world; making the audience laugh, connecting us to life in the jungle. We soon love this captivating young man who is thriving in the practices of the everyday as he lounges in a hammock upstage and snacks on a banana. Imbitide marries and has a child—he is content. His wife keeps the fire and cooks yucca in abundance, they have never known the taste of hunger.

Whose story is it to tell? Do we have the right to tell the history of the indigenous Amazon? How can this story belong to Akron, Ohio?

The play fades into its third landscape: “The Blancos in La Chorrera,” foreign men, the “blancos,” arrive with gifts of beads, jewelry, and machetes. The Uitoto are gracious for the gifts and welcome the men in, offering sacred tobacco as symbolic friendship and giving these new arrivals the trust of the tribe. The audience cringes at the blancos manipulative behavior --we know from imperialist history this can’t end well for the Uitoto. Blancos ask “Can you bring us the milk that comes from the trees?” Jairo stabs a free standing wooden beam and the symbolic stage tree magically pours out white milk from its wound. The spiritually sacred milk of the Uitoto is valued natural rubber.

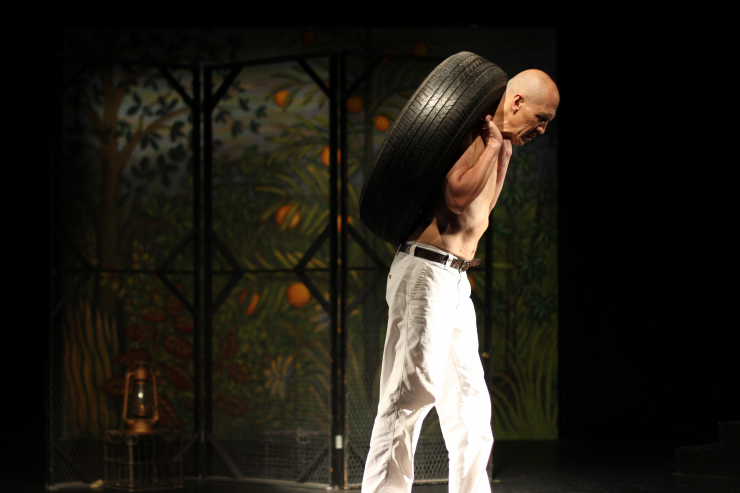

Imbitide’s excitement bubbles as his people are promised that the more “white milk” they collect the more gifts they will receive. As they go into the depths of the jungle it becomes clear that the blancos are dangerous; they ride alongside the tribe with guns at the ready. Jairo narrates the struggle of his people carrying the heavy loads of rubber on their backs. Blancos shout death threats, women and men collapse from exhaustion, and two scared boys are shot for running away. A poignant moment hits as Jairo crosses the stage holding a single Goodyear tire on his back. The weight of that tire sinks in, the audience makes the gut wrenching connection between past and present.

The Uitoto venture to the blanco camp, upstage on the traditional proscenium. Jairo sits on a pile of wooden crates and morphs into a worker who mocks the suffering of the native people. The audience is horrified as this twisted man laughs at three captive native women, who will soon be at the disposal of over 150 paid laborers. He cracks a joke about a girl who wasn’t strong enough and died the night before, explaining that his master doesn’t take any women younger than nine or older than fifteen. Another laugh, then Jairo transforms back into our beloved Imbitide.

Still at the blanco camp, Imbitide climbs a tall, wire fence that stands center stage. We watch his face as he looks through the wire holes, a window into a house. He witnesses men beating his father to death. The chief refuses to scream. Unable to watch his father suffer, Imbitide makes an agreement with the blanco that leads to his enslavement.

The lights on Jairo fade as the lights rise where James Slowiak stands at a podium and relays a series of facts such as “It is estimated that for every ton of rubber 3,000 indigenous people lost their lives.” And “At the beginning of the twentieth century the Uitoto had a population of approximately 50,000 people, during the Rubber Boom, the population fell to between 7,000 to 10,000 from disease, displacement, and the atrocities committed upon them by the rubber industry.”

This series of facts comes alive in the most impactful moment of the play, a beaten down Jairo carries a wooden barrel on his back. He stands center stage, his eyes meet the audience. He turns the barrel upside down and a plethora of white rubber balls fall to the floor. Some bounce, others roll under the audience’s feet—the stage floor is covered with them. Watching all these rubber balls fall simultaneously to the ground makes the destructive history an even more present reality. It is breathtaking, the evidence lies at the audience’s feet, and the realization hits that we are all implicated in the injustices committed against these people.

As the white rubber balls settle on the stage floor a musician strums a guitar, and Jairo begins an improvised dance—a dance of death, a dance of mourning, a dance of despair. Each rubber ball represents another Uitoto life lost. His dance flows through the entire playing space. He and his people, now, know the taste of hunger, the burden of loss.

The forced labor pushes Imibitide to the brink of death. Exhaustion renders him useless and he is tossed into the river with the bodies of the dead. As he floats down the river an inner strength revitalizes him and he returns home. Now the leader of the tribe, his depleted people struggle to hide in the depths of the jungle. In an attempt to save his people from the monstrosities they now face, he goes on a solo mission to locate an escape route his father once spoke of. In his absence his tribe and his family are massacred, everything that was his life is now decimated. In the play’s final landscape, the strong Uitoto man walks fearlessly to his death. He echoes the words of his father “a quick death is a good death”.

There is no escape from rubber in our society, and there’s certainly no way that we are able to go back and fix what has already been done. Prior to seeing this show, I was completely ignorant of the rubber industry’s toll. Death of Man not only brings this horrific past to life, but it opens up a powerful dialogue for healing. This unheard history is a part of us; it lives and breathes in the great American love affair with the automobile. This really did happen, and it happened here in the Midwest. Natural rubber was shipped to Europe and then sent to factories in the states including Akron, Ohio.

After taking the time to experience the culture of the tribe and presenting Jairo’s work, a new conclusion was made by the indigenous leader who previously questioned ownership of this story. “I was going to tell you that you don’t have the right to tell our story, but now, I think, that yes, you can tell our story because you are telling the story of your city, your community, and we would like to help you tell it more authentically.” The rubber industry’s violent past is a story that belongs to Akron as much as it belongs to the Amazon. I would even say it belongs to all of us. Every American owns a piece of this story—from every child with a bouncy ball to the millions of drivers with four tires and a spare one sitting in the trunk of their cars.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this fascinating article. An excellent Colombian film that came out in 2015 also covers the damage and violence the rubber trade has wrought in the Amazon region:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wi...