Are Theatre Critics Critical? An Update

It wasn't exactly an ambush, but the first question actor Bernardo Cubria posed to me as a guest on his theatre podcast was about a complaint that actors have about critics. I was his sixtieth guest, and his first theatre critic.

Why do so many reviews, he asked, just summarize the plot and not give an opinion? Later he complained that a critic’s opinion in a review upset a friend of his who had spent “three months of her life” dedicated to her show.

Finally, we got around to something I actually had something to do with, a review I wrote, “a really negative review of a show I was in that I loved,” he told the listeners, and that “my future mother-in-law loved.” I also reviewed his performance in the play, saying it was “less persuasive” than some of the other cast members’. “It hurt,” he said.

All of this seemed to illustrate an observation he made in his introduction: “At some point in their lives, theatremakers develop hostility towards theatre critics.”

Should Anybody Care About Theatre Critics?

“I believe the trade of critic, in literature, music, and drama, is the most degraded of all trades, and has no real value,” Mark Twain wrote in an autobiography that was published only recently, a century after his death. “However, let it go. It is the will of God that we must have critics and missionaries and Congressmen and humorists. We must bear the burden.”

Must we bear it much longer? As Chris Rawson, theatre critic for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, put it in 2010 when introducing a panel discussion, “what is the future of theatre criticism—is there a future of theatre criticism?” And (something he did not ask), should anybody care?

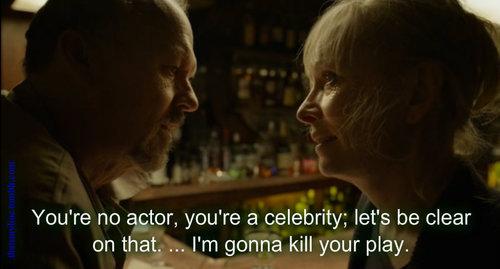

Photo by Youtube.

For several years now, the state of theatre critics and criticism has become a popular subject of think pieces, panels, blog posts, and conversations on Twitter. It heated up recently with the attention paid to the negative depiction of a critic in the film Birdman, or the Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance. On the night it won four Oscars, including Best Picture, J. Kelly Nestruck, the chief theatre critic for The Globe and Mail in Toronto, Tweeted: “All theatre critics lost tonight when Birdman triumphed, but at least I won my Oscar pool.”

Is theatre criticism crucial (critically important) for anybody or anything—like, say, for the theatre? Are theatre critics too negative (do they criticize too much)? Is the field dying out (in critical condition)?

I first wrote an article entitled “Are Theatre Critics…Critical?” in 2010 for the national online newspaper that I served as New York theatre critic. The publication has since gone belly up. I think it’s time for an update.

Five years later, the question of whether theatre critics are critical is really three questions, playing off the various meanings of the word “critical”:

- Is theatre criticism crucial (critically important) for anybody or anything—like, say, for the theatre?

- Are theatre critics too negative (do they criticize too much)?

- Is the field dying out (in critical condition)?

What Is a Theatre Critic? Are They Better Than Vermin?

A theatre critic is a “malicious, cowardly” person who cannot see the beauty in a flower because she cannot put a label on it. That is what the ex movie star turned first-time Broadway director Riggan Thomas (Michael Keaton) tells the New York Times theatre critic Tabitha Dickinson (Lindsay Duncan) in Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman. “You risk nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing,” the director tells the critic as they both drink in a theatre bar. “I risk everything.”

Critics are “really failed playwrights or actors who become critics out of desperation,” the playwright character says in the Broadway revival of Terrence McNally’s It’s Only A Play, which singled out the (actual) New York Times theatre critic Ben Brantley as “a pretentious, diva-worshipping, British-ass-kissing twat.”

This is nothing new. From The Man Who Came To Dinner to The Worst Show in the Fringe (in which a critic is kidnapped), theatre critics have been depicted as intimidating, pompous, and unpleasant—yes, usually cultured and erudite, but also condescending and out-of-touch…and sometimes (All About Eve?) villainous. In Ruthless! The Musical, the daughter of a character named Lita Encore says: “Oh Mother hates anything to do with show business; she’s a theatre critic.”

Classic Movie Hub.

The only theatre critics that get unmitigated affection seem to be under ten years old.

But if the image of the theatre critic is more or less fixed in people’s minds thanks to these works, the definition of a critic is now in flux, due to the convulsive changes in journalism, and the rise of the Internet. It has been estimated that there are some 300,000 arts-related bloggers (I am one of them). Can any of them be considered professional theatre critics?

John Simon didn’t think so. Asked whether bloggers could replace the diminishing number of critics from traditional print publications, Simon said “no matter how wrongheaded a critic may be, he or she’s always better than the bloggers. The bloggers are the vermin of this society.” He said this in an episode of the television program Theatre Talk in 2010 when he was the critic for Bloomberg News, after thirty-six years as the theatre critic for New York Magazine. Shortly afterwards, Simon lost his job at Bloomberg News—and started his own blog.

The American Theatre Critics Association, ATCA, the only national organization of American theatre critics, has been struggling with their criteria for membership. Right now they admit people who, as they put it, write professionally, regularly, and with substance about the theatre. But what does professional mean at a time when only a handful of critics derive all their income from their reviews? (At a recent conference of ATCA, only three out of fifty attendees raised their hands when asked whether they made their living entirely as a critic.) And has the Web (with its hyperlinks and reader interaction, etc.) changed the definition of substantive?

The International Association of Theatre Critics, or IATC, has a 10-point “Code of Practice.” Examples (put more succinctly than they do): 4. Be open-minded. 6. Be alert during a performance. 7. Use concrete examples to back up your evaluations.

The Canadian Theatre Critics Association has a “code of ethics” which is also something of a code of practice. (“The critic should, whenever possible, prepare in advance of a performance”—by reading the handouts and if possible the script.)

I believe that a good critic needs three basic qualities:

- Independent judgment rooted in education and experience.

- An ability to articulate one’s views with clear and engaging prose, backing up their points with accurate and concrete examples.

- Taste generally shared with the intended audience.

Are Theatre Critics Crucial?

In his provocative way, Kristoffer Diaz, the playwright of the Pulitzer finalist drama, The Elaborate Entrance of Chad Deity, who earlier had sparked a conversation on Twitter by calling for a moratorium on productions of Shakespeare, once said he would prefer the work of playwrights be reviewed by other playwrights. Few theatre people would go so far as to call for the elimination of theatre critics, and when I followed up with Diaz, he said that what he wanted was “a more diverse group of critics (age/race/ethnicity/aesthetic).”

Most theatre artists will admit, however grudgingly, what Vickie Ramirez, a playwright and founding member of Amerinda Theatre, told me: “Reviews are absolutely needed; they are a critical part of the process.” But sometimes, she said, critics pick targets unfairly. “Nobody’s saying don’t review,” Ramirez said. “Time it well, and maybe bring out the big guns just for bigger productions.”

On the other hand, at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center, the site each year of the National Critics Institute, several panelists discussing criticism told how a review of a small production early in their career gave them a crucial lift. “I was in a very low place, and it told me to keep going,” playwright Adam Rapp said of such a review when he was twenty-nine. “It’s such an interesting, complicated relationship between artists and critics,” Rapp said. “Some critics are doing great things for theatre,” he added. “Some out there should be removed from the planet.”

Theatre critics can help careers, boost morale, and even aid a creative team in refashioning a show. But they do not exist to inspire and enrage theatremakers. Their purpose is to guide theatre audiences, to provoke thought and discussion, and to offer an independent assessment of an evanescent experience, for posterity. As Pauline Kael liked to say: “In the arts, the critic is the only independent source of information. The rest is advertising.” Theatre artists’ widespread misunderstanding of the critics’ purpose may help explain at least some of the hostility—but not all.

Theatre critics can help careers, boost morale, and even aid a creative team in refashioning a show. But they do not exist to inspire and enrage theatre makers.

Are Theatre Critics Too Negative?

I began writing reviews of college productions for my school newspaper, which didn’t always sit well with classmates in those shows. One with whom I’ve kept in touch still brings up decades later how unfair I was in my assessment of his Snoopy in You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown. Although he says it as if he’s joking, I’m not so sure. That classmate is Peter Marks, now the long-time theatre critic for The Washington Post. The moral of the story: Few people like to be criticized.

Many theatre professionals have learned to accept the negative review as “a part of the job,” as Bernardo Cubria put it to me after the podcast—or, if not accept, at least ignore. When Charles Durning was starting out as an actor, he recalled, Joseph Papp told him: “The only people you have to please are the producer and director and yourself. If you think you have to please a critic, you shouldn’t be in the business.”

But the resentment and hostility by theatre artists is palpable, and I suspect it has much to do with what they perceive as the critics’ power. After all, how many of these same theatre people happily watched Simon Cowell eviscerate American Idol hopefuls? How many read Gawker and gleefully participate in hate-Tweeting such shows as Peter Pan Live? When people cackle over infamous flops like Carrie and Moose Murders, they are not remembering the plays themselves—which few people actually saw, since the shows ran only for a day or so—but the cleverness of the reviews. We live in a society that accepts harsh negative assessments—as the price for high standards, or as a source of schadenfreude entertainment (take your pick)—while at the same time proudly embracing a tradition of fighting the power.

But how much power do critics really have over a show? “We only have significant influence in certain narrowly defined circumstances,” says Wall Street Journal critic Terry Teachout.

Peter Marks championed Ragtime and Side Show productions in D.C. that transferred to Broadway…and wound up commercial bombs.

“I’ve never understood why theatre reviewers are counted on to be box office oracles,” Marks says. “Producers who rely on reviews rather than gut are not producers."

“It’s hilarious that the current hit play on Broadway [It’s Only A Play] is about the power of a reviewer. Well, then again, it’s a comedy."

“Critics can spotlight talent, add momentum, move the needle a bit. They have tremendous impact—in the margins.”

Philadelphia Inquirer theatre critic Wendy Rosenfield relishes critics’ roles as “catalysts, not just judges.” But she bristles at the most frequent complaint she gets from theatre artists—that a review of hers will discourage people from seeing the show. “I’m in journalism, not public relations,” she replies. “It’s like saying covering political scandals will stop people from voting, or covering a team’s loss or a player’s errors will stop people from attending sporting events.”

The best response to this complaint is that an honest assessment, even if severe, does more to promote the art form than indiscriminate praise.

A debate emerged early last year, prompted by HowlRound Director Polly Carl’s call for criticism based on “positive inquiry” and what Princeton theatre professor Jill Dolan called “critical generosity.” As Dolan put it, it seems that “mainstream” critics “revel in their power to destroy productions they don’t like for reasons that are always political, as well as aesthetic, and always masked by the ‘objectivity’ that power bestows on their work.” Critics of this position remarked that this was itself an ungenerous assessment, presuming to intuit nefarious motives.

It is harder to argue that mainstream critics are set on destruction when they reportedly wind up praising more than they pan. Ben Brantley and Charles Isherwood, the two main theatre critics of the New York Times, gave positive reviews to forty-five percent of the shows they reviewed over the past ten years, according to a recent calculation by Broadway producer Ken Davenport, who owns the review aggregation site Did He Like It. Only twenty-nine percent were negative, Davenport determined, and twenty-six percent were mixed.

Yet, the theatre community can be forgiven for being distrustful of a group of professionals who can seem at times to be rude and disrespectful. They see some who cover theatre taking for granted our free tickets, boasting about leaving at intermission, as the Wall Street Journal’s culture writer (not critic) Joanne Kaufman did. They see some of us as gratuitously mean-spirited: one critic Adam Rapp would probably like to see removed from the planet is Charles Isherwood, who wrote an entire piece about how unfair it is for him to be reviewing Adam Rapp’s plays since he hates them so much. Isherwood’s general point is worth making—if a critic consistently dislikes the works of a particular playwright, does it make any sense to continue to review them? But there was irony in his naming the playwright he was claiming not to want to hurt any longer.

Theatremakers also see critics’ efforts to be witty and engaging as too often at the expense of a show and the people who worked so hard to put it together. Chicago Tribune movie (and former theatre) critic Michael Phillips likes to quote a line from Lorrie Moore’s short story “Anagrams” in which a character wonders whether “all writing about art is simply language playing so ardently with itself that it goes blind.”

To these complaints, I’ll quote film critic A. O. Scott, who wrote:

Criticism is a habit of mind, a discipline of writing, a way of life—a commitment to the independent, open-ended exploration of works of art in relation to one another and the world around them. As such, it is always apt to be misunderstood, undervalued and at odds with itself. Artists will complain, fans will tune out, but the arguments will never end.

Scott wrote this after he lost his job as a film critic on TV, and was asked to deliver a talk on the future of criticism. “The future of criticism is the same as it ever was,” he said. “Miserable, and full of possibility.”

Is Theatre Criticism Dying?

After the death in 2010 of Mike Kuchwara, the Associated Press’ theatre critic, and arguably the first or second most influential critic in the nation, there was some speculation that he might not even be replaced. But the Associated Press then advertised to hire “a theatre critic and pop culture reporter”—that’s one person with two jobs.

Kuchwara’s successor, Mark Kennedy, does do some pop culture reporting, as well as “some TV and music and smaller bylined stories,” he told me. “More editing, too.”

Other outlets have eliminated reviews entirely, such as Backstage (where I wrote at one point), or laid off their staff critics and rely on freelancers. This is not just happening in the United States.

“Entire review sections—especially on the Sundays—have been shut down, arts budgets are being slashed,” Tim Walker wrote after he was laid off from the Sunday Telegraph, “and the critics that are still standing are having to pick and choose between productions because they cannot physically get to them all.” He quoted “one leading impresario” as noticing that the critics who attended one of his shows were “young, spotty, out of their comfort zones and clearly exhausted, having been diverted at the last minute from other tasks at their hard-pressed media organizations.”

This outraged Jake Orr, the founder of A Younger Theatre, a combination publication and production company whose aim is to champion “the emerging generation.” Orr Tweeted: “Well, honestly, Tim, I can name many ‘young, spotty’ Internet critics that have a depth of understanding of how to write about theatre.” Lighting designer Tom Turner added: “And thus the ‘ex-theatre critics writing column inches bemoaning the lack of themselves’ industry was born.” Indeed, to an outsider, this does seem part of an almost comic pattern: Each UK theatre critic forced into retirement writes an essay proclaiming the death of theatre criticism, which is then attacked by online critics and younger theatre artists as self-centered and self-serving…and inaccurate.

Does Kennedy of the Associated Press think the doom-sayers are correct—that theatre criticism is dying?

“Yes and no,” Kennedy replies.

I think those critics who focus only on theatre are in trouble, but I see a future where critics are omnivorous—going from Miley Cyrus, to Tom Stoppard, to Interstellar, and readers would follow them from CD to stage and screen. I see more hybrid reporter-critic roles, too. Basically, fewer people will be covering the more mainstream of cultural offerings to gain the most traction.

Others see dedicated, diligent theatre critics proliferating online—on blogs, on chat rooms—who need only to figure out how to make a living from it.

Personally, although I don’t expect to have a full-time job again as a theatre critic—as I did years ago for Newsday—I hope to continue to write about theatre for any outlet that’s a fit. This includes Bernardo Cubria’s Off and On theatre podcast. Shortly after our chat, he invited me to appear regularly on Off and On, to review shows for his listeners.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I wrote a not entirely dissimilar piece for Americans for the Arts about last summer's national Dance Critics Association Conference: http://blog.americansforthe... ... Critics had value in the business model of print newspapers, and we don't need to dig too deeply to also see that they also had value in audience development (but that's not why they were part of print newspapers.) While perhaps no critic can truly drive ticket sales, critics play a crucial role in the arts ecosystem bridging the divide between professional and public participation in the field. How can we help today's artists and productions develop an authentic connection with new audiences if the public no longer trusts critics?

I am a playwright and co-artistic director of what I like to call a "microtheatre." I never quite understand -- or perhaps, don't *share* -- the thin-skinnnedness of my colleagues who claim never to read reviews or who get upset by bad ones. Theatre and criticism: it's not rocket science. You put up a show, a critic reviews it, and you hope s/he liked it. A good review (especially in the StarTribune, or for New Yorkers, the Times) generally means more tickets sold, and a negative review (or lack of reviews) generally means fewer tickets sold, so as a writer or producer, you hope it's good. But in the end, you have the right to stage whatever you want, and a critic has a right to his or her opinion.

I have to say that Mandell's no-nonsense article appeals to me. But I wonder why we in the theatre profession have endless forums and panels about criticism and whether the calls for "constructive criticism" are just requests to "like MY work." Does a bad review hurt some people? Yup. Is war hell? Yup. Next subject, please?

UK critic Mark Shenton has just posted a piece on his blog entitled The past, present and future of theatre criticism, which is worth quoting from:

Not only are the traditional distribution channels of the print media changing, but the online world is also one in which blogs, bulletin boards, chatrooms and Twitter are offering far more outlets for opinion. Everyone has an opinion, of course; but what what they now have, too, is the means to broadcast and publish it, whether in the form of a 140-character tweet or contributing to one of the numerous theatre websites. It means that everyone, now, is a critic. Or at least, has a voice.

The result is that far from being the ultimate word on a production, critics are only the start of a conversation around it, not the end of it. That’s something I personally welcome: it means that the conversations that critics are part of are now richer, as critics have also had to become more engaged with both those they write for and those they write about than ever before.

But it also means that there’s a lot of noise to filter before readers get down to the authority of people actually appointed (rather than self-appointed) for their expertise and knowledge. And amid all the noise of the internet, authoritative voices are even more important than before, not less

http://shentonstage.com/the...

Plot summary reviews are noisome as they cater to the most shallow of interpretations, the Literal. The purpose of art is to transcend the Literal, that fiction of Reality, and see–feel– sense the deeper meaning of life, and to be entertained in the fundamental exercise for the mind of learning something new. What I would prefer from reviews is enlightenment about cultural or artistic definitions (whether they be interpretations by the critic or straight from the horse's mouths,) that would help learn something of original intent. Criticism that is just personal opinion or observation, can be wonderfully enlightening, but seems more about personality cult than about the Art of Criticism. imfho

To be fair, a lot of contemporary playwriting is very prosaic and offer very little beyond the literal. I suppose that great deal of that is the influence of television and film on theater writing. I certainly see these plays in readings and even getting full productions.

Yes, there are critics who rarely go beyond the literal, but you also have to ask: What are the plays they are seeing?

Bernardo Cubria answered his own question about why so many reviewers only describe the plot when he told you how much your review hurt. One can't have it both ways.

I appreciate the perspective on criticism, and its purpose. Critics may be in service to the audience, not the art, but the truth is that they impact both.

Of course. It's probably safe to say that a review is likely to have more of an impact on the artist than on any individual member of the audience.

The question is: Should this fact influence the critic's writing, and if so, how? It's a legitimate subject of debate, I think.

The artist and the audience have much in common, but their interests are not 100 percent the same.

I think it already does. That's why certain reviews seem like they almost have a personal relationship with particular playwrights. I think the question is how as a critic do you deal with that awareness? There are people who attempt to say that critics are no longer necessary because of the access to social media, but still think a review, even a bad one, provides a validation for the average theater-goer

I want to clarify something: I believe that criticism exists to serve both the audience AND the art. Its primary purpose does not include pleasing (or displeasing) the individual artist, but I think most reviewers do see themselves as laboring for the greater good of the art form. This is probably part of the reason why, as you say, what they write "provides a validation for the average theater-goer."

I think readers appreciate that a specific show is put into a larger context.

Critics should describe the production before they give a judgement. That is it. There really is nothing else. It sounds too simple but if you give a complete enough description that says everything.

Plot summary + judgment = the least interesting, most Consumer Report-ish kind of reviewing to me.

I agree, and disagree, with both of you. Critics should describe the production, certainly. I don't see this as their sole or primary function, but I also don't see it as lacking in interest (unless the show they're describing is lacking in interest.)

At least for us in Off-Broadway theatre critics, and the press they give us, are vial to our success. There are no marketing dollars I can spend that have the positive impact of a decent (not to mention a glowing) review from the New York Times. We see a bigger increase when the print piece comes out, especially if there's a photo, but the online posting also results in a huge increase in sales.

With the reduction in staff and print placement at the major newspapers it becomes harder and harder for us to get that sort of exposure. While a rave may not equal success on Broadway it certainly does Off-Broadway.

Solid stuff here and I hope you are right about multiculti reviewers as guides for less mainstream arts...let's keep pushing for that. I have a couple observations about criticism that I feel are important to think about.

1 is in relation to the point about the responsibility to the audience. I'm always worried by the fact that reviewers and critics see so many more shows that most theatre audience goers and certainly much more than the average American or even New Yorker...this often leads me to believe that the relationship to the audience is at a major disadvantage in terms of the experience of the theatre goer. Often reviews are just in opposition to the general feeling of the audience, in fact mostly the response of the audience is almost completely absent from most reviews. I can recall many Living Theatre reviews that were just nasty when 95% of the audience was clapping, smiling participating and yet the report to the readership of the publication indicated that nowhere...

2. Neither critics nor theatre makers are succeeding wildly at introducing new audiences to theatre or creating the large scale cultural movement that is needed in this country. We all have to do a better job of keeping that in mind as we create shows and critique them. As of right now there are too many shows that run for 3 weeks to small audiences with one or two reviews that advance only the agenda of both self serving artists or self serving reviewers.

3. Lee Breuer said something Monday during his retrospective at The Segal Center that I found thought provoking...go figure,,,but he likened theatre critics to the human being as observer and creator of our world in terms of quantum theory. That we create our universe the way we observe it and in turn theatre critics create value or lack if value the way they observe art. I think taking our duty this seriously as creators and critics can help with points one and two.

There's a lot to say and I have often blasted back at critics in comments sections when they have disrespected Judith especially...and we have to find a way to change this whole part of the industry because it is not serving itself to it's fullest potential nor the culture, which I think your article here illuminates well.

Thanks for your words.

Brad, I really like your comment; the quote from Breuer reminds me that the criticism that most of our patrons ever read serves the need of the market (should I stay or should I go?). But in a more democratized landscape of theatergoing and theater making (at least, that's the ideal, right?), what critical needs are being met in our community by the critic? The advancement of the field, yes, but maybe only those of us IN the field are interested in reading about that. The great "long form critics," like the founder of my theater, Robert Brustein, were plentiful, valued and well-read once. But that was before I could read.

I, personally, have no barometer for great, and populist, criticism, which elevates the value of the art form within its readers— what would it look like today? What is it like to read my daily paper and have that experience with criticism instead of, "huh, I guess that sucked…" It's a larger cultural shift than just the sobering fact that good criticism is not marketable these days. If you ask me, maybe most readers in the mass market lack the historical/cultural/artistic context to appreciate and engage with the dialectics of deep, informed criticism. Was this ever true? I don't know. Like I said, I was born in the 80s.

Thank you for your kind words about my essay (although I'm not sure where I said anything about "multiculti reviewers as guides for less mainstream arts.") You make some intriguing points, to the extent that I understand them (quantum theory?!!) But they also make me feel obligated to point out that, contrary to popular belief, critics are human beings. A critic has a right to his individual views, as does any member of the audience. His responsibility to his readers (viewers/listeners) is to offer his own informed opinion, not to report on the reaction to a show by other members of the audience, even if that reaction is in the majority and contrary to his own. (A critic is not barred from doing so,of course, and I often read reviews that do just that.)