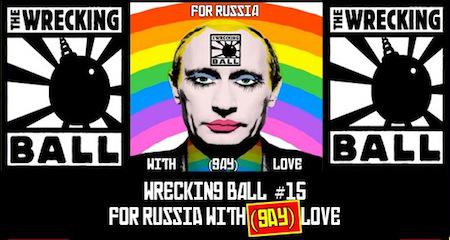

The Artist as Worker

Solidarity in To Russia with (Gay) Love

In the Daniel MacIvor short scene, “Kevin,” featured in The Wrecking Ball #15 – To Russia with (Gay) Love, an impossibly cute little boy tells us that the problem is that, “You are all persons and not a people and you are all here.” That is, we are not individually the body politic and certainly not on a global scale, and yet here we are at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre in Toronto gathering, in solidarity, for the series of short acts by Canada’s queer and allied playwrights and creators. There is something deeply comforting about gathering as a community to share outrage, frustration, and hope for change. But are we just preaching to the choir when we create and attend protest theater?

Photo courtesy of Matt McGeachy.

There has been widespread condemnation of the “gay propaganda” law—so-called because it is actually just de jure discrimination—signed by Russian president Vladimir Putin in May 2013, criminalizing the promotion of any “non traditional” sexual or family relationships, with an added emphasis on “protecting the children” from the propaganda of homosexuality. (Though not, it seems, the children of same-sex couples, who may now face the forced break-up of their families in the name of “family values and morality”?)

There is something deeply comforting about gathering as a community to share outrage, frustration, and hope for change. But are we just preaching to the choir when we create and attend protest theater?

This condemnation is taking place against the backdrop of the upcoming winter Olympics at Sochi in 2014, where the international community and the International Olympic Committee have proven utterly feeble in pressuring for any kind of change to the law. Indeed, now any Olympic athlete who admits to being openly gay would, it seems, be subject to punishment under this law. The law as it stands is unacceptable—though it is by no means the only such anti-homosexual law in the world—and the inability or unwillingness of anyone to apply pressure prior to the Olympics leaves one feeling pretty hopeless about any kind of meaningful action when billions of dollars in ad revenue aren’t at stake.

So what are we to do about this, sitting as we do thousands of kilometres/miles away? More specifically, what are we as theater artists to do?

The Wrecking Ball provides an answer to that question, and the answer is solidarity through art. Founded in 2004 by director Ross Manson and playwright Jason Sherman, The Wrecking Ball is an occasional theatrical event where new work by established artists, taken directly from the headlines of the day, is rehearsed for no more than one week and presented to the public. Although started in Toronto, there are now Wrecking Balls that happen in other Canadian cities such as Victoria, BC; Edmonton, AB; and Ottawa, the nation’s capital. The Wrecking Ball seeks to promote the creation of immediate artistic responses to the news of the day, borrowing its aesthetic from the Living Newspapers of the US Federal Theater Project during the Great Depression; it is not only political, it is immediate.

To Russia with (Gay) Love was presented on the same day in solidarity with Zee Zee Theatre’s NYET! A Cabaret of Concerned Canadians in Vancouver, and featured work from Sonja Mills, Shawn MacDonald, Daniel MacIvor, Catherine Hernandez, Marcus Youssef, Dave Deveau, and Ronnie Burkett. The scenes ran the gamut, from expressing outrage and poking fun at Putin to drawing attention to the plight of LGBT people in other parts of the world, to calling for direct artistic action. Youssef’s “Gay People, Da, Da, Da” featured Gavin Crawford in a side-splitting spoof of Putin addressing a Canadian audience and explaining his penchant for appearing shirtless whenever possible, which is totally not gay at all (cough, cough). Sonja Mill’s absurdist “Vladimir the Beautiful” spoofs the sycophantic advisors catering to Putin’s every whim at their five minute morning strategy meetings, and could have been pulled from the pages of the great Russian satirist Bulgakov.

Perhaps most moving, for me, was a short scene written by Ronnie Burkett wherein the artist as a middle aged man confronts the memory of his younger self to justify his decision not to go to Moscow to perform, since to go there he would risk imprisonment for his sexuality. His younger self reminds the middle-aged artist of the artistic and sexual awakening he had in Moscow. The sexual awakening involved a young Czech with a big dick; the artistic awakening involved learning that to be a real artist means having a point of view, even if it means risking persecution. In effect, the memory of the artist as a young man serves as a jolting reminder that success and safety with no risk is not really success at all. Theater can be a rallying cry against complacency, but not if we, as theater artists, are complacent. All of the evening’s scenes were presented with only a few hours of rehearsal time, and the energy and rawness in the room was palpable. It was energizing.

It also, as big events in the world tend to do, made me think about the role art has to play in social protest and change. Events such as this one differ from direct protest theater in obvious ways. None of us were on the streets of Moscow staging guerilla theater and none of us risked running afoul of the law. Not a single person there, I would venture, changed her or his mind about the terrible law in Russia; we all came there having weighed the law in the balance and found it both wanting and reeking of horseshit. So what were we there for, aside from seeing some great new art?

Solidarity.

Feminist and cultural theorist Sara Ahmed said in her 2004 book, The Cultural Politics of Emotion, "Solidarity does not assume that our struggles are the same struggles, or that our pain is the same pain, or that our hope is for the same future. Solidarity involves commitment, and work, as well as the recognition that even if we do not have the same feelings, or the same lives, or the same bodies, we do live on common ground." [Emphasis added.]

Common ground and work. That is what drew artists and audience together for The Wrecking Ball #15. Implicit in Ahmed’s statement is the notion that solidarity across international boundaries and cultural divides requires something active; it requires work. What we witnessed at this gathering was artistic work from all involved, work that gave voice to the myriad feelings of despair and anger and isolation and frustration at a situation that is, quite frankly, beyond our immediate control.

Artists are workers, and by offering this labor to a group of people, To Russia with (Gay) Love reminded us of the common ground on which we stand, regardless of how far apart we may be geographically. In presenting these works both in Toronto and Vancouver, these artists and the audience reaffirmed our mutual commitment to our brothers and sisters in Russia who have been shoved into closets of Putin’s making. Although, maybe, no one in St. Petersburg or Moscow or Sochi will ever know these specific scenes, they effectively laid out our point of view: as artists, we must point out the common ground on which we stand, and hope like hell that others do their part, too.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here