Asian American Theater

The Question of Home

Producer Jane Jung and I welcome you to a week on HowlRound that explores various Asian American artists’ perspectives on the field-at-large and specifically the upcoming 2014 National Asian American Theater Conference and Festival theme of “Home: Here? There? Where?” In our own ways, we explore the related themes of separation, exile, (im)migration, (dis/re)location—and how these experiences impact our lives and work as theatre artists. How do they define our creative process? Does it question or shape concepts of home, identity, nation, allegiance, and hope? One doesn’t have to be an expert on Asian American or culturally specific theatre to engage with the inquiries around art-making, community-building, displacement, diversity, and inclusion. More, what now? Use #theNAATF and #newplay in Twitter.

*

When the Miss Saigon controversy hit Broadway in 1990 I had just played Ali Hakim in my high school production of Oklahoma. Our Curly and Will Parker were African American and we had a public school cast that would seem radical by most professional standards. You see, I was living in the Bay Area, specifically a Filipino enclave. Our mayor was a Japanese American and everywhere I turned, I could see people of color leading government, school systems, and business. New York City, Asian American theatre, the politics of “yellowface” and representation were worlds away. Of course, because I didn’t know those issues existed doesn’t mean that they weren’t alive and well. My biggest concern was who was going to give me a ride to 7-Eleven for a Big Gulp and were they auditioning for the musical Grease. I had found my people!

I came to California when I was six-and-a-half. The experience was jarring—I didn’t have the language to communicate. Though I was born and raised in the Philippines during a period of Ferdinand Marcos’s martial law, the sepia version of my life in metro Manila had a steady stream of characters, lively parties, abundant love, and a deep and rigorous religiosity that blurred with superstition. It was a world built for me. All that changed when I landed in the Bay Area. That scale, vibrancy, and knowing became me, my nuclear family, and reruns of Leave it to Beaver. I learned from an early age the difficulty in expressing ideas and connecting with others—both through language and culture. America was where my body was, but my sense of home was thousands of miles away. Every day I worked to try and change that.

In Mrs. DeRidder’s first grade class, everyone botched my last name, so I changed the way it sounded. In my late teens, I was on a path to study radio broadcasting (remember radio!?). I thought if I engineered my vocal quality enough, I would sound like an announcer, devoid of any remnants of race and class—more American. People took to it. I mean, I made it easy for my fellow citizens. In my search for Americanness, I somehow—bit by bit—cast away my Asianness. Honestly, I still called everyone an aunt or uncle or cousin despite any evidence of relation. I still took trips to the Philippines where a dinner out meant seating for ten to twenty-five people. To this day, my mom insists that I speak Tagalog, though I remind her that I was encouraged to release it in favor of the English I was learning from Sesame Street. I was trying to rebuild myself for this new world.

Coincidentally, as David Henry Hwang, Tisa Chang, B. D. Wong, and numerous others were trying to gain some footing on Cameron Mackintosh’s casting of British Caucasian actor Jonathan Pryce’s role as a Eurasian, my family sold their home and moved from a very diverse place to, unbeknownst to us, a town rumored to be a KKK hub in the 70s. I don’t think my parents deliberated about that when they bought the new house for a good price. Just because he wasn’t on our radar didn’t mean the Grand Dragon wasn’t still in town. We went from this relatively blue collar suburb with the smell of adobo in the air to a place where a lot more people wore cowboy boots. Don’t worry, we still trekked to attend my parents’ Friday night Santo Niño gatherings (prayer groups around the image of the Holy Infant Jesus, one of the most beloved and recognizable cultural icons in the Philippines), complete with lukewarm traditional food, adults ballroom dancing and a free-for-all karaoke. Clearly, we were in a community, but oddly not of the community.

In the intervening years, I would be reminded of my “otherness” when a car would swerve by me and my friends on the California/Oregon border screaming “Go home!” It would happen politely, in a quaint bed and breakfast in South Dakota when the owner would compliment me on my English. Or in New York City, when a a playful student rushed to edge of her school playground and chanted, “Ching Chong! Ching Chong! Ching Chong!” I know it’s nothing compared to some of the violence people have encountered, but still when I’m wearing my Banana Republic button-down, hair done just so, and American English perfected in speech class, I feel immune. My heart then jumps and for that humbling moment I understand abjection. Regardless of how thoroughly “American” we might feel, being the perpetual foreigner is a part of how Asian Americans are seen.

Asian Americans have historically been ignored and misrepresented in the media, by not being perceived as American but as the “perpetual foreigner” and through instances of yellow face.

*

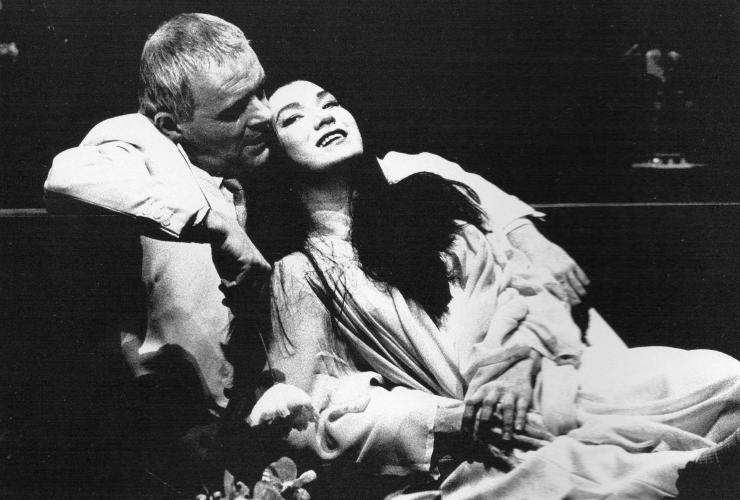

David Henry Hwang’s Broadway production of M. Butterfly, which won the Tony Award for best play in 1988, put Asian American theatre on the national and international map. Hwang was lauded as the first Asian American playwright to be produced on the Great White Way, but few knew the history that brought him there. Asian American theatre emerged in the 1960s and the 1970s with the founding of four theatre companies: East West Players in Los Angeles (currently headed by Tim Dang), Asian American Theater Workshop (later renamed Asian American Theater Company) in San Francisco, Theatrical Ensemble of Asians (later renamed Northwest Asian American Theatre) in Seattle, and Pan Asian Repertory Theatre (currently headed by founder Tisa Chang) in New York City. Soon companies and performance groups were launched, including Ma-Yi Theater, National Asian American Theatre Company (NAATCO), Mu Performing Arts, Lodestone Theatre Ensemble, Slant Performance Group, 18 Mighty Mountain Warriors, Second Generation, and many, many others.

*

Twenty years later, I find myself running Second Generation (2g) in New York City. Welly Yang, who was cast as Thuy in Miss Saigon, wanted more opportunities for Asian American performers and therefore, founded 2g in 1997. After playwrights Lloyd Suh and Carla Ching ran the company, I took over in 2012. Even with experience working with some of NYC’s finest Asian American artists, I am a relative newcomer to this community. In fact, I had not directed a full-length production for an Asian American company since I was given my professional start at San Francisco’s Teatro Ng Tanan (Theater for Everyone) in 1993. Playwright Sung Rno first invited me to participate in the city’s Asian American scene through the Ma-Yi Writer’s Lab, a group he founded. While the mainstream theatre has slowly changed, Sung’s invitation served as an antidote for some of the loneliness.

Some might say I’ve been lucky to direct quintessential American works, but this invitation to the mind, capacity, endurance of the Asian American artist has become a profoundly fulfilling and sometimes sobering journey.

The summer before I took my post, a controversy erupted around La Jolla Playhouse’s casting of The Nightingale. The musical is set in “mythological China” with a cast of characters with Chinese names. Of the twelve in the cast only two were Asian American, none were leads. Perhaps Asian Americans hadn’t progressed much in the twenty-two years after Miss Saigon. Now, instead of reaching for a big gulp, I had a scotch or two. These were no longer names in a newspaper, but friends and colleagues who, like me, wanted to be more than a token. Some might say I’ve been lucky to direct quintessential American works, but this invitation to the mind, capacity, endurance of the Asian American artist has become a profoundly fulfilling and sometimes sobering journey.

2g was founded to increase Asian American representation in theatre. Asian Americans have historically been ignored and misrepresented in the media, by not being perceived as American but as the “perpetual foreigner” and through instances of yellow face. In AAPAC’s recent review of Broadway and nonprofit theatre, Asian Americans were the only major minority group to have their numbers decrease, from 3 percent in 2006 to 1 percent in the 2008–09 and 2009–10 seasons. Moreover, Asian Americans were the least likely of all major minority groups to play roles that were not racially specific.

This insistence for our stories and collaboration grows. According to the Center for American Progress and AAPI Data: From 2000 to 2010—and since the release of the 2010 Census—Asian American/Pacific Islanders are the two fastest growing racial groups in the United States. Also, Asian Americans are a rapidly growing part of the electorate, making an average gain of about 500,000 voters every four years. Naturalization of Asian immigrants has outnumbered naturalization of immigrants from any other continent, contributing to our nation’s economy in numerous ways. And the size of the Asian American labor force has been growing faster than for any other racial or ethnic group. The majority of the United States is projected to be people of color by 2043. More and more, my high school reality, though imperfect, became something that inspired.

During my tenure, I will draw upon 2g roots of large-scale presentations and reach (Welly’s years) to its rootedness in the Asian American theatre community (developed in Lloyd and Carla’s time) to find a merging of those two to create a new level of influence, collaboration, and inclusion for Asian American artists. Though I had run theatre programs through government, academia, and nonprofits, it’s been a hugely humbling time to understand the history, complications, and great sacrifice of pioneers in the Asian American theatre field, many of whom I sit with on the national Board of Directors for the Consortium of Asian American Theaters and Artists (CAATA). CAATA envisions a strong and sustainable Asian American Theater community that is an integral presence in national culture.

Through theatre I’ve explored difficult subjects like genocide, education reform, micro-aggression with an aim to engage a modern audience. Stories and artists that are on the margins are brought to the center. Now, with 2g, we’re building on my colleagues’ decades-long work to grow the nation’s acceptance, perception, and respect for the vision, contributions, complexities, struggles, and artistry of Asian Americans. It’s all very new to me. And deeply worthwhile.

Join us.

*

About CAATA

In September 2003, six Asian American theatre companies attended a convening sponsored by Theater Communications Group. The companies—Pan Asian Repertory Theatre, East West Players, Ma-Yi Theater, the National Asian American Theatre Company (NAATCO), Second Generation (2g), and Mu Performing Arts—began discussions to hold the first National Asian American Theater Conference. Conferences and Festivals have since been hosted in Minneapolis, New York, and Los Angeles.

CAATA, dedicated to advancing the field of Asian American theatre, will present the 2014 National Asian American Theater Conference and Festival (ConFest) to be held in Philadelphia, from Wednesday, October 8 through Sunday, October 12. This year’s ConFest is the fourth such national convening since the group’s first gathering in Los Angeles in 2006 and the first time the event will take place in Philadelphia.

The Conference, held in tandem with Festival performances, includes plenary speakers addressing topics including casting and representation of Asian American performers, Asian American activism and social justice in performance, new performance forms, and discussions on the meaning and complexities of home for Asian Americans. Break-out sessions, held throughout the Conference, delve into areas including professional development, artistic practice and craft, and further explorations of the ConFest theme, “Home: Here? There? Where?“ For additional information on the 2014 ConFest, passes and individual tickets, please visit 2014.caata.net. View the livestreaming schedule and future video archive of the conference here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Reading your experiences growing up mirrored what I've had as an african-american. N-words shouted at me out of cars, constant references to my race in non-minority company. Heck even safe to say reactions to my proper English are a sign of subtle racism too.

Weird world out there. :-/

"The majority of the United States is projected to be people of color by 2043."

Serious question: At that point (2043) will people be willing to get rid of all the laws that make it legal to discriminate against white people (affirmative action, quotas, preferences in college admission, etc.)?

If not then, when? (Or never?)

Greetings, Below are a few links to articles on "Affirmative Action". You might be interested in who actually benefits the most from affirmative action.

TIME: http://ideas.time.com/2013/...

ASK THE WHITE GUY: http://www.diversityinc.com...

THE ROOT: http://www.theroot.com/arti...

And let's not forget Honolulu's Kumu Kahua Theatre (www.kumukahua.org) for sustaining the work of Pacific Islanders Americans and the unique cultural mix of Hawaii....