Breaking Out of Queer Boxes

Nabra Nelson: Salam Aleykum. Welcome to Kunafa and Shay, a podcast produced for HowlRound Theatre Commons, a free and open platform for theatremakers worldwide. Kunafa and Shay discusses and analyzes contemporary and historical Middle Eastern and North Africa, or MENA, theatre from across the region.

Marina Johnson: I'm Marina.

Nabra Nelson: And I'm Nabra.

Marina Johnson: And we're your hosts.

Nabra Nelson: Our name, Kunafa and Shay, invites you into the discussion in the best way we know how, with complex and delicious sweets, like kunafa, and perfectly warm tea, or in Arabic, shay.

Marina Johnson: Kunafa and Shay is a place to share experiences, ideas, and sometimes to engage with our differences. In each country in the Arab world, you'll find kunafa made differently. In that way, we also lean into the diversity, complexity, and robust flavors of MENA Theatre. We bring our own perspectives, research, and special guests in order to start a dialogue and encourage further learning and discussion.

Nabra Nelson: In our third season, we highlight queer, MENA, and SWANA or Southwest Asian/North African theatremakers, and dive into the breadth of queerness present in their art.

Marina Johnson: Yalla, grab your tea, the shay is just right.

Nabra Nelson: Queerness is not a monolith. As their art intersects with racial, gender, and sexual identity, queer SWANA theatremakers are constantly breaking out of boxes. Even within queer and/or SWANA spheres, some artists are pushing boundaries and redefining what those broad identity categories mean. Join two such artists in a discussion on the present and the future of SWANA theatremaking.

Bazeed is a non-binary Egyptian immigrant based in Brooklyn, New York. They graduated with an MFA in fiction from Hunter College in 2018. In addition to being an alliteration leaning writer of prose, poetry, plays, and personal essays, Bazeed is a performance artist and singer. They're a current fellow at the Center for Fiction and a past fellow of the Asian American Writers Workshop, the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at NYU, and the Lambda Literary Foundation. Their work has been supported by residencies from Hedgebrook, the Marble House project, and the Millay Colony. Peace Camp Org, Bazeed's first play, has been presented at La MaMa Theater in New York, the Arcola Theatre in London, and the Wild Project in New York. To procrastinate against facing the blank page, Bazeed runs a monthly world music salon and is a slow student of Arabic music.

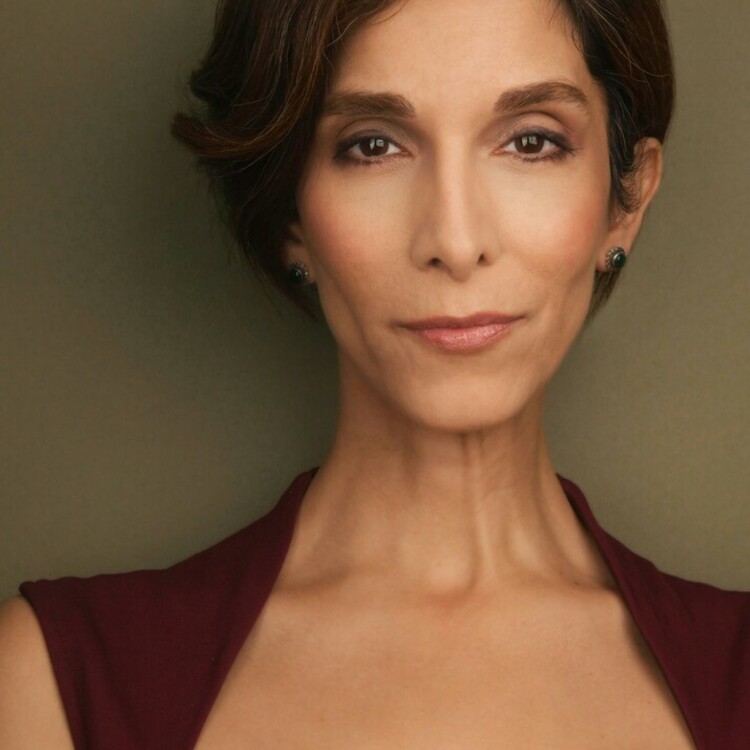

Marina Johnson: Pooya Mohseni is a multi-award-winning Iranian American actor, writer, filmmaker and transgender activist. She recently appeared in the world premiere of The Sex Party (Menier Chocolate Factory) in London. Her other stage performances include the Pulitzer and Obie-winning play English (Atlantic Theater Company), Hamlet (Play On Shakespeare Festival), One Woman (United Solo), She,He,Me (National Queer Theater), Our Town (Pride Plays), Galatea (The WP Project), The Good Muslim (EST), White Snake (Baltimore Center Stage), and the Audible production of Chonburi Hotel & The Butterfly Club (Williamstown Theater Festival). Her film and television credits include Law & Order: SVU, Big Dogs, Falling Water, Madam Secretary, Terrifier and See You Then, streaming on all digital platforms. She's part of the advisory council for The Ackerman Institute's Gender & Family Project.

Marina Johnson: Hello. We are so excited to have you both with us today. I have to tell people that are listening, we've already just been chatting together for several minutes and I have laughed harder than I've probably laughed in weeks and weeks. Pooya and Bazeed, just excited for this conversation today with you.

Bazeed: It's so nice to be here. Thank you for asking us.

Marina Johnson: Yes, so we're going to start with a really broad question because you both are artists who do a lot of different things, but I guess the first question is how do you define yourself as an artist? Well, the audience has heard your bios, but how do you define yourself? Do you want to start, Pooya?

Pooya Mohseni: Oh, I was going to wait for Bazeed, it's like alphabetically. Sure, I'm an Iranian American actor, writer, script consultant, and a trans activist born in Iran and have been in New York since 1997.

Bazeed: I'm Egyptian. I'm a multidisciplinary artist. I spend the most hours writing prose, poetry, and plays, but I'm also a performer. I'm a massage therapist in training. I've done a little bit of stage acting and then some voiceover work and things like that, but mainly I'm a writer, I would say.

Nabra Nelson: Now to just immediately ask you the opposite question because we talk a lot about the boxes that folks are put into, how they're redefining themselves, and this episode is really diving deep into that idea of breaking out of boxes. What are the boxes that you feel put into? We're going to follow up with that on how are you breaking out of them. But what are the conversations you keep being asked to have, the identities that you've been defined as? Or how do you define those boxes that you're put into?

Bazeed: I mean, it's interesting. It's May 25th, so Pride Month is a few days away, and I'm like, "Busiest time of my year." It's like when everybody remembers I exist. There's definitely the queer box, which is also... I've started spending a little bit more time in Cairo than I had been in the past ten years or something, and I really noticed that sort of in the ways that folks introduce themselves, the political labels of identity are in an American context and especially in the creative, more radical queerer spaces that I tend to find myself in, that it's definitely just more in the everyday language of how people talk about themselves than, "Hey, I'm so-and-so, and we're going to find things to connect about later in conversation." But the sort of "I'm queer, I'm this, I'm that, I'm the other thing," definitely feels like a way of introducing oneself, a way of talking that feels very American right now. It's not obviously unconnected to the news cycle and our social media platforms and all of the things, but it does feel specific. It took me going back there more consistently to really feel that.

Pooya Mohseni: For me, my history of being me is it goes back to, let's say 1994, when a therapist tells my mom that your child is a transsexual. I mean, now that word just feels like it belonged... Well, it did belong to another century. To then get to a point that it's like I'm an activist and I do panels, I speak on Persian-speaking panels, I'm out, everybody knows. When somebody asks me, it's like, "Well, who knows you're trans?" I'm like, "If there's somebody left that doesn't know I'm transient," I'm like, "They obviously haven't been around." Then the whole journey in there of what a trans person had to do twenty-five years ago, which is like you transition and you hope to God that you can pass so that you can pass as cis and basically disappear into the cis hetero world, which then it was a privilege if you could, and I had that fortunate and unfortunate privilege to be able to disappear, hide, and then hope to God that nobody finds out, and try to blend.

Then, to then get to a point of saying, "Why? Why am I doing this? I haven't done anything wrong. I haven't committed any crime." I talk about that, even with my name Pooya, because sometimes I've been on talk shows and people are like, "Well, your name is a male name." I'm like, "Your name is a name, so what?" They're like, "Well, why didn't you change your name?" I'm like, "Well, that has a very long history. But what you should ask is, as an adult, why did I choose to keep my name?" It's the fact that, first of all, it is my name. It's a name that has always been my name. I like, it fits me, it connects my parents to the child that they had. The name itself has no gender. Also, it is a sign to the world, especially to the Persian-speaking world that knows exactly what that name is, that first I'm not hiding, I am proud of my journey to have gotten here, and that also allows other people to see you have nothing to apologize for.

This whole journey, I feel like the boxes forever change and either we can control those boxes. I've been a textile designer, I've been a massage therapist, I've been married, I've been divorced, I've been an actor who was in the closet, then I've been an actor and activist who's been outside of the closet. One of the things I always say to younger people is everything is always evolving. Something that you are now, you may not be five years from now, but the only thing that I would ask people to do, you choose what box you want to be in or if you want to break out of it, don't let anybody else tell you where you should be or where you shouldn't be because you have one life and it is only worth something if you invest yourself in it.

A little side note that it's this whole idea of religion having been weaponized against queer people, this whole idea, it's like I always say, "I have clergy blood in my veins." Nobody can tell me what God wants me to do because either we're all God's children or none of us are God's children. I'm never going to buy the fact that some people are God's children and they can tell other people what God wants and it's like whether God loves them or not. No, it's either within all of our hearts and up to us to seek it and find it or not. They can't have it both ways. What you were saying about boxes, I don't think there's anything in this world that's truly a box, it's all purely arbitrary.

I'm very proud and fortunate to have been born into one world that gave me very specific ideas about gender, identity, and where should people belong to then have had the privilege of hearing other people, seeing other people's lived experiences, and younger generations as well as older people who have just made my life so much richer by their experiences and what they've learned to then go from that person who wanted to be in the closet, transsexual, to get to a point of today, I'm Mama Pooya. Who knows what the hell I'll be tomorrow? But whatever I am, that love inside for myself and for my community, as a queer person part of the community, that is indeed a privilege that cannot be put in a box, because it's a unicorn bubble.

Nabra Nelson: Yes, we should be asking what unicorn bubbles are you put into instead. I love that. Thank you. That's so, so beautifully said, Pooya. Absolutely I think this idea of boxes, they don't exist, but there's this constant, I think especially for queer and MENA folks, pressure by the outside world, like the external world wants to create a box so badly and it's endlessly frustrating and why we invited you both into this episode. I think everyone in this season is breaking out of boxes because I think queerness inherently is unboxable, it's anti box. But if you look at your work, if I was to try to tell someone what Pooya and Bazeed do or who they are, it would be very, very difficult to define. Your work is so expansive, so multidisciplinary, there are so many different aspects to your work and ways that you approach your work as well as how you define yourself as artists, as people, and beyond your art.

Do you feel as though you have to work to break out of those boxes, whether that's the queer box, the SWANA box, all of these kind of definitions that folks have put into your work? Or do you feel as though that's just been an inherent nature of how you approach your art and your work as a person, that it's broken those boxes by nature of the work itself, if that makes sense? Do you feel like that's an intentional breaking or if that's just a breaking because that's how you come into the world?

Bazeed: It's interesting. I think for me, I apply to so many things, I apply to residencies, fellowships, grants, whatever, so I actually am constantly sort of putting myself into the same boxes that I'm trying to break out of because you want to be legible to an admissions committee, and in the US that means a very specific thing. If you are telling an immigrant story, you better have your elevator pitch plus whatever immigrant plus family closeness and queerness tale or whatever. You need to package it in some way where they can see the production if it's a production or they know how to sell it if it's a novel or something like that. There's I feel like this sort of constant grooming of oneself to be like, "Here's who I am in the zeitgeist that you are defining for me right now to fit into," so there's that piece of it.

I think I've sort of given up on the possibility in my lifetime of ever writing a play that won't be seen as an Egyptian play, a Muslim play, a whatever the fuck it is kind of play. I also recognize that many people who sort of end up being able to create work as just a painter, like Etel Adnan was able to be a painter and a poet and all of these things. I don't know necessarily that Lebanese is attached to her as quickly as somebody who doesn't have her, as big a name. There is this sort of place that one can get to where if they're valued enough in the creative community, they can transcend their identity in a weird way. Even just that that exists as a differential tells you something about how North America sometimes thinks about artmaking and the place of marginalized identities and marginalized stories in the offering of larger, whether it's American theatre or anything else.

I've kind of given up on... I'm also like when you leave me to write about the things that I know about, I'm probably writing about queer ass Arabs mostly. Are there other projects that have nothing to do with my identity? Yes. I'm working right now on a libretto for an opera about the pandemic, and it's from an extended erasure poem that I made from Daniel Defoe's creative nonfiction account of the Bubonic Plague in London. It is so far removed from anything that has to do with my identity as a queer Muslim Egyptian. I have no idea if somebody's going to want that from me or whether I'll have a harder time having people pay attention to that than my play about the queer Egyptian coming home to his dying father and all the clear lines of investment that are already legible to anybody sort of hearing that as a setup. I'll stop there because I could say a lot more, but...

Pooya Mohseni: I was listening to Bazeed and thinking it's like how does that pertain to me? I say this funny thing about life in general, that it's like everything I do, I have all of it being guided by one notion, how am I going to look back on this on my deathbed? I know. In a way, it's very SWANA because of course it's like who can think of death the way we do?

Bazeed: I was literally thinking, "That's so Iranian."

Tala Ashe, Hadi Tabbal, Pooya Mohseni, Marjan Neshat, and Ava Lalezarzadeh in English by Sanaz Toossi produced by the Atlantic Theater Company at the Linda Gross Theater. Directed by Knud Adams. Scenic design by Marsha Ginsberg. Costume design by Enver Chakartash. Lighting design by Reza Behjat. Photo by Sara Krulwich/the New York Times.

Pooya Mohseni: I know. It's so... But there is almost in essence it's like how does this fit into my life as a bigger picture? But of course, me being the sassy queer bitch that I am, it has this idea, I'm like, "I want it to be something that I look back on and say," I'm like, "Wow, I was an insane sassy bitch and thank God I was that person," and then laugh myself to death. It's like, see, that's the part of me that's not so Iranian because I'll take the death part, but I'm like "I want it to be a moment that I'm going to laugh so hard at the insane life I had that I'm going to laugh off the bed and crack my head open and die," and that's going to be the way that I'm going to go. But when I look at it at the larger picture, then it feels like what is it that I want to do today?

I have this belief that it's like if you wake up that day and you think this is the last day I'm going to have, how can I make this day count? If you have the good fortune, again as an Iranian person who was born in a revolution and who grew up during war, if you have the good fortune to still be alive by the end of the day and be able to go to sleep, then hopefully you have the thought of "Hopefully tomorrow I can do whatever I didn't get to do today." In that sense, that gives me so much peace in a way that I'm like, "You can only do what you can do today."

It's like being an actor, this idea that you're always waiting to make it and for the thing to happen and the person. But I try to, as somebody who has come very close to death many times in my life, either being assaulted by a stranger or almost being run over by a car or being arrested by the morality police in Iran or having been in an abusive relationship, and as someone who has also lost a parent, I have great respect for living, living that day. That's why I always say, I'm like, "People think I'm a very bougie, sophisticated person," but I'm like, "I'm a very simple person in the fact that what are my needs and desires today?"

It all comes down to: what is it that I want to leave behind? I want my life to have had value. As someone who has gone through so much, I'm always looking for something that can justify the things that the younger version of me went through. I want to be able to give meaning to the fact that my mom at forty-nine or fifty decided to leave her country so that her trans child could have a life. I want to feel that I am putting my life to some good use that the young queer Iranians or the young SWANA queer folks or it's like whoever in some way can see something in my story that will help them lead a more centered, more authentic, more truthful, more self-embracing life. That whatever part of my journey can accommodate that, then that gives my life meaning.

I am trans, yes. I am a woman in my forties, yes. I am an immigrant, yes. I was born in Iran, yes. I'm all of those things, and I feel that every time I walk into a room. Last year I had the good fortune of originating a role in Sanaz Toossi's play English at Atlantic Theater that has since won an Obie. I've won an Obie and the rest of my cast, and a Lucille Lortel Award, and it just won Pulitzer for Best Drama. On one side, that had nothing to do with my transness, but it had a lot to do with my Iranianess. But two years before that, I did She He Me by Raphael Khouri through National Queer Theater. Yes, the character was a Lebanese trans woman, so that was my trans side. When people ask me like, "Well, what do you want?"

I'm like, "I want good stories that portrays characters who are humans, who have agency, who are not written by some, for lack of a better term, a colonialist," whether it happens to be by race, ethnicity, or gender supremacy that is writing a character that I'm going to play as this other fetishized, tokenized, single faceted character that is only there to satisfy the desire of the writer that knows nothing about the character they've written. As an artist, as a consultant... When I go in as a consultant, I always tell people "I want to honor your story," and hopefully it's a story I can honor. "I want to honor your story, but I want to help you make this particular character that you obviously don't have a full grasp on and help you write this character in a way that, when people watch this or read this, they're not going to think “oh, that character is a full character and this character, I don't know why the hell this character is here." We've all read those stories.

I always say the simplest example that everybody can understand is the older I'm getting, the more I'm having a problem with female characters that are written by old white men because their agency is just to accommodate the hero's journey, which is usually a man, or characters of color that are there to either be saved by a white character or to be the oracles along the path of the white character to find itself. I feel in that sense, I have this joy, this curiosity when people want to write really good stories and they are seeking help, I'm more than happy to be there. When they have written characters that they want these characters to be fully fleshed out and be something that really connects, I want to do that. Sometimes it's one part of me, sometimes it's another part of me, sometimes it's all of me, all of it together.

I feel as an artist who has gone through the things that I've gone through as a human in my life, the historical things that I've been privy to, that I try to do anything I touch as best as I possibly can. If I can't, if it's beyond my scope or if it's something that, like Bazeed said, if it's something that's going to take another fifty years for us to get to that scope of being able to realize, it's like you can write queer characters without it being labeled as a queer story. It's a human story. Even if that's the case, then I will just try to do the best that I can and hope that the people that come after me, they will find some value in what I've did and then add to it and it's like take it to places that I would've never even dreamed of. That gives me comfort, that all I have to be is just one ring in a long mesh of evolution.

Marina Johnson: Pooya, just jumping off of one of the many things that you said, because we could I think take this in a bunch of different directions, but we actually have Raphael Khouri and Sivan who... The writer and then director of She He Me on different parts of this season, and we'd love to hear what that was like for you, the play itself, your work on it. Can you expand more upon that?

Storytelling is a divine occupation.

Pooya Mohseni: It was beautiful because I had never seen anything like it, that there are three characters, I mean three queer characters, but then to be more specific, there's a trans woman who has a child who is grappling with being able to be a parent in a world that wants to take that away from her. Then on the other side, a gay man and a gender nonconforming person. Obviously it felt very close to my heart because these characters, one was Lebanese, I don't know if the other one was Saudi, I don't remember exactly where each character, but our neck of the woods, and the things that they had to live through. That part of it, in a way, made it hard because I knew, from personal knowledge and experience, what these characters must be going through. But it gave me joy because these characters were written and Sivan's direction, which just had such generosity, focus, and respect for these characters, and of course Rafael's writing.

It was at the height of the pandemic, so we basically got to do the whole thing in isolation on Zoom, which I think was very appropriate in a way for the play because all of these characters were isolated from their families, from their immediate worlds, and then somehow they were connecting across borders and distance and all of that. It was heartbreaking, but it was also... I'm getting emotional, but I'm just going to go ahead. It made you feel wonderful for being able to tell these stories and then have, like the character that I was portraying that was based on a real person, to then have that person have seen that performance and have been moved by it. I always say, "Storytelling, it's a divine occupation," because I mean, where would we be... I hear so many people say so many different things. It's like storytelling is the soul of society. It's the equalizer. It's the thing that shows us society in a way that we don't get to see it because when we're in, it's so hard. It's kind of missing the tree for the forest.

But as a storyteller, you get to show people things that they may not see, even if it might be right next to them, but you can also show them how things can be. You can show them possibility, you can show them hope, you can show them the insidious violence that exists in a society in a way that we're not comfortable addressing it in real life, but then you get to go and see it in a play or in a movie or in a reading, and it imprints on you, somewhere in your mind, in your soul, whether it gets you to see reality in a way you'd never thought before or it gets you to feel that you're not alone or that your story has value.

All of that was true about She He Me, all of that, that I hope many, many queer SWANA people got to, at the very least, see a play on Zoom because most of them live in countries that they cannot see a queer play in person at the fear of... I don't have to explain what those fears are. But to be able to do that, that's what... I don't even call myself an artist. Artist, it's so abstract. I mean, yeah, I was a painter and a drawer. Yeah, sure, if you want to call that art. I'm a storyteller, that's all I am. People have been doing it for as long as there have been people and they will continue to do it. It's because I see the value of those stories. That is how we keep our hearts alive.

Marina Johnson: Oh, Pooya, thank you so much for that. I mean, I think just the phrase that I feel like of the many that I can pull from that, like storytelling is a divine occupation. We've all been in this world of being able to tell a story for the first time, you said it was so special because you hadn't seen it. That's I think some of the beauty of what's coming out of this work right now and work that you and Bazeed are doing. It's so moving to hear about that experience. I hope that everyone gets to see this piece soon, whether it's on Zoom or not. I think Zoom theatre gets a lot of hate, but I love that we can watch these plays while people are in different countries together, what a beautiful thing.

Pooya Mohseni: It was the equalizer, and I don't want anybody to forget, Zoom became a theatre equalizer. People that were not in New York, people that were not in a cosmopolitan area, people that usually wouldn't travel—they got access. I know that it's in New York or some artistic hub were like, "live theatre." I'm like, "Yeah, that's wonderful." But like you said, Zoom became an equalizer. I am very grateful that that happened because I think a lot more people got to see a lot more things that in a regular day at an actual theatre would not have necessarily seen.

Marina Johnson: Agreed. Bazeed, talking about other plays that, something that I haven't seen before, I first discovered your work in an anthology; Peace Camp Org is a queer anti-Zionist musical comedy about summer camp, which was really exciting to read there. You've mentioned that it accidentally got you into theatre, so I want to hear about that. But also, Nabra and I at MENATMA in Michigan this past year, got to hear some of your full length play, Kilo Batra: In Death More Radiant, and so that was really exciting to see too. It was something that I had gotten emails about for a while that was like, "This work is being developed." I was like, "Oh, tell me more." I would love to hear more about I think how this accidentally got you into theatre with Peace Camp Org, and then also the stories that you've been telling since that are stories that I think haven't existed in any way like this.

Bazeed: Yeah, thank you for the question. Peace Camp Org is actually an autobiographical work and is in an anthology with Raphael Khouri as well. We were in the same festival together. Actually, that's where we first met was our work being curated together into this thing and then ending up in this book. But how I wrote that play, I mentioned that just because it's funny just how small actually queer theatre world is, and then when you add the also SWANA thing, and it's sort of like we all have already met each other in various... I think I did a reading with Pooya one time in New York a while ago. Anyway, so I just mentioned that to be like, "Oh my God, the web of us is pretty nuts." Anyway.

Pooya Mohseni: We're taking over.

Bazeed: We're taking over. That's it. We are the forest, we are the trees. For Peace Camp Org, that was actually... I was not writing theatre at all when I started that project and wasn't thinking that it was going to be a play. I had quit my full-time corporate job to try to be a writer and also try to do all the performance things that I had been interested in that I didn't have time for. I was like, "This is your time to be creative, , just do all the things." Dan Fishback, who's a queer theatremaker himself, had this fellowship where folks who were queer who had not done a ton of solo performance could apply and, over four months I think, sort of develop a work together. It was like we'd meet for six hours, sort of get prompts, we were constantly making stuff. It was just this very creative workshop environment that I had not ever really been in, and there was a showcase thing at the end.

For that, I wrote a twenty-minute, one-person piece called Peace Camp Org that was about my experience going to the summer camp when I was sixteen years old as an Egyptian delegate to this place that, at the time, was this magical, idyllic, just heaven-scape that turns out to kind of be a nonprofit, industrial complex, sort of greenwashing Zionist project ultimately that was doing a lot of bringing kids together to make peace, but not actually talk about structural things ever. Or there was no diversity of funding sources of who wanted this project to exist and state department involvement and just like everything weird.

But that was the story of how I came to America, and it connected to stories of my relationship with my mother at the time who was ailing, sick, and dying. That turned into this autobiographical anti-Zionist musical comedy about summer camp. When I was curated into a festival the next year to kind of expand it and was paired with Sarah Schulman, who was already doing a lot of writing about pinkwashing and doing her own anti-Zionist activism work, and we were paired for that festival. She gave me the full hour that we had to develop the play, and she was the dramaturg for it at the time. That was my first play. That's how I started writing for theatre. Then, the play got into the Fresh Fruit Festival, it got into this Global Queer Plays Festival in London with Raphael. It got published... It just had a life that I wasn't expecting for it. It's won a couple of awards, I'm very happy to say.

Nabra Nelson: You did not tiptoe your way into the field. I feel like that's a huge project, so many intersections.

Bazeed: As it turns out, no, but it was... As it turned out, no. It was great. It was an incredible thing to be able to say that the very first work that I ever had put up in New York at La MaMa Theater was this queer anti-Zionist project; I wouldn't expect to be able to say that. Also, the happy accidents that had to happen and not... I actually shouldn't say accidents because there were people who were invested in a particular story being told, and they're the reason it got told, whether that's Dan Fishback with the fellowship, like Sarah Schulman with developing the play with me, everybody who ended up being involved, La MaMa Theater for making the space for that kind of making. It's not a typical story, I don't think, to be like, "Yeah, I made this thing that was..." Anyway, so that was that.

Nabra Nelson: Yeah, and tell us about the other work since then, your theatre work and anything else you've been working on.

Bazeed: Oh, you mentioned Kilo Batra. You mentioned Kilo Batra actually. That's another example sort of, again, I'm very luckily having worlds open up to me that I was not planning for, was not... Because the only reason I got connected to that project at all is Kamelya Omayma Youssef, who is my co-writer on that play. She is a poet, playwright, multidisciplinary writer as well, performer who is from Dearborn, Michigan, had a preexisting relationship with a host of people, which is the company who they made the play, they produced the play at the Arab American National Museum, and she brought me into that project. They were interested in making something, they had been making work about the life of Cleopatra already, and then found a play by Ahmed Shawqi, the Egyptian poet, that was the very first play to have ever been written entirely in Arabic verse. It was his sort of response to Shakespeare's Cleopatra trying to kind of be like, "Well, your interpretation kind of sucks. Here's her from our perspective."

They were interested in writing a play that was just in response to that work, like the prompt was extremely broad from a host of people. It was Kamelya and I's job to figure out what's the story we're going to tell here. We're both coming at it from this place of “I am an immigrant to America,” so my positionality around Arab culture there. She is a first generation American born in a place where she got to speak Arabic growing up most of her life and be surrounded by a robust and extremely visible present Arab community, and that's her positionality. We're looking towards Shawqi trying to be like, "Yes, here's this guy who's going to rescue Cleopatra from Shakespeare's shitty ass interpretation of her," and then he writes a terrible misogynist honor killing of a play, honestly. That's the history we're contending with, and that's the legacy we're contending with.

The play ends up kind of being about that, of how do we keep encountering and re-encountering our histories when they've all been told with the same isms over and over and over and over and over again. One thing that was interesting when looking at that project actually, when we were researching it a little bit, was to see that Edwards Said's Orientalism, like many, many, many of its tenets already sort of existed in how the Romans were imagining the Egyptians at the time, how the Egyptians were being written about in the Roman record.

It was interesting to be grappling with this play in the middle of the pandemic with everything that was going on. We started writing it a few days after the Black Lives Matter uprisings in June 2020 when we had to travel to Detroit in this... Bringing pee funnels because we couldn't go into the bathroom for the trip, couldn't go into the bathrooms because of COVID and nobody knowing anything going on, all of that, and sort of being so deeply rooted in a history that was so present, just feeling like we're kind of in this timeless space where... Yeah, I don't know, it was strange.

It was strange to be doing research on that project, kind of being in a very Arab city in America, it was my first time in Dearborn, and thinking through what the death of Cleopatra did to modernity and the Roman sort of renaissance that happens there, the fall of Egyptian culture after that, everything that was sort of happening that far back and seeing how much of it was still present with us. I feel like that's something I keep encountering in my work is that things don't change that much. We are answering a lot of the same questions in a lot of the same ways and thinking we're making progress, but cycles.

Kilo Batra by Bazeed with Kamelya Omayam Youssef, commissioned by A Host of People and the Arab American National Museum. Directed by Sherrine Azab. Set, Prop, and Projection Graphics by Dorothy Melander-Dayton. Projection Design and additional graphics by Jake Hooker. Costume Design by Levon Kafafian. Lighting Design by Chantel Gaidica. Dramaturgy by Amanda Ewing. Composed by Donia Jarrar. Stage Management by Emily Erlich and Shardai Davis. Assistant Direction by Rasha Almulaiki. Performed by Faith Berry, Zeina Fawaz, Chris Jakob, Sam Watson, Frank Sawa, Bazeed, and Kamelya Omayam Youssef.

Nabra Nelson: There's this beautiful story in every piece that each of you have talked about. I love how much there is behind it and the ripples that they each have. I'm wondering if each of you tell us, give us a little sneak preview into what's coming up for you, what you're excited about that you're working on right now so we can get excited and look out for your work.

Marina Johnson: Yeah, or even other things you've been part of that we haven't talked about, if you want to highlight those.

Pooya Mohseni: As we were talking about all the things that are lacking, but by the way, Bazeed, I was actually talking about Cleopatra to somebody, a white man, and he was so adamant about the fact that, "No, this is what happened to Cleopatra. This happened, this happened, and she committed suicide." I'm like, "Well, I wasn't personally there, neither were you unless you really have great facial moisturizer." But there are also accounts that say this woman who was that determined, that resilient, and that ruthless, at that moment, she would come up with a different tactic of trying to hold onto power for herself and for her country instead of just committing suicide. There are accounts that believe she was actually killed by Octavian, but he's like, "No, she committed suicide." I'm like, "Well, I'm glad that you're that sure and you were there and you saw it happen," because I'm like, "I'm saying that I wasn't there and I'm saying it's possible that this happened, but you're just sitting there," just like, "No, this is exactly what happened, and I know how it happened with Octavian."

I'm like, okay, white man privilege. Okay, we're not going to go further with this because I'm already saying I wasn't there and I know you weren't there, even though you are so certain that you know what happened.

Bazeed: Well, because admitting that Octavian killed her or whomever somebody sent from the Romans would also have to be like, "Okay, so this extremely powerful general killed a woman who had been cornered and locked up in a temple for the last, I think three months or something." It's again the story of a heroine who's beautiful, sexy, and loves sex who kills herself is so much more in line with what...

Pooya Mohseni: I know. I'm like, "Oh, I have come to the end of my road." I'm like, "Oh, for fuck's sake, I'm so over that narrative." But again, it's part of it is like you're seeing taking ownership, as an Italian man, taking ownership. No, this is exactly what happened. I'm like, "I'm seeing how attached you are to that story, and I'm not going to waste my breath because I'm not going to live long enough to make this argument really worth it. You believe what you believe, and it's like the history will just find its truth somewhere along the way." But I feel like we're still fighting similar battles.

Bazeed: For sure.

If my only contribution is to put an Iranian trans character out there who is confident, who is strong, who has truth and depth to her experience as a trans person, and yet finds a place in a community and in a family, in an Iranian traditional family… then I will be very grateful for that.

Pooya Mohseni: What you were saying, it's like whether it's kind of as SWANA people we're still dealing with colonial supremacy of this idea that lighter is better, so that's one part of our identity that we're grappling. Then, there's the innate misogyny in the cultures that we come from, it's like whether it happens to be cis hetero supremacy towards queer people or it's like the misogyny of men towards women and anything feminine.

One of the things that I wanted to do, which I was very fortunate to find a partner that wanted to also do this with me about two years ago, was I thought as an Iranian American trans person, and when I say that, it's like all of the above together or separate, there are not a whole lot of happy stories. We're always like, "There's something tragic." It's trauma porn, we get assaulted and you get disowned. It's like you go through all the variations of tragedy that people like us are portrayed to have. We said that, "I want to tell a story of an Iranian trans character," kind of very loosely based on, I guess who I am, just like I'm Iranian, I'm trans, so that loosely. Having this person have their story shown in a positive way that they do find somebody that they care about, that somebody that cares about them, and it's not a coming out story, but also make it very Iranian. What does that mean? It's like, "Okay, you've met somebody that you like and this person wants you to meet their family."

I know the Iranian culture, I'm not going to presume that I know about... It's like every other country in that region, but I imagine it's kind of similar, the mother of the boy being like, it's like, "Is she good enough for my son?" It's trying to find that. How would the family deal with finding out that this beautiful, accomplished, eloquent woman who on the surface is everything that they would like for the son of the family, but that then they find out is trans? How do they come to terms with it? Again, we didn't want to make it a tragedy. For us, it was more interesting to show the journey that someone can have from coming face-to-face with that information and how do they find their way through it. Again, it's a short film. The whole point of it was we wanted to make our proof of concept so that people could see this story and hopefully help us make the feature.

I will say it, and I have said it, and I will continue to say, if my only contribution is to put an Iranian trans character out there who is confident, who is strong, who has truth and depth to her experience as a trans person, and yet finds a place in a community and in a family, in an Iranian traditional family, and if that's all I can put out there, then I will be very grateful for that. The film has now been edited, it takes a while to get to this point, and is ready for the festivals. My friend and I always say it's like it's our baby, it's like it came from the fact that I put it out there, and he always says that. He's like, "You put it out there in the world, and you said..." I guess I did, I'm the sassy woman that I am. I turned to him two years ago and I said, "This is a story I want to tell and I want to tell it with you."

All of that experience was a “yes and” experience. I'm like, "This is what I want to say." It's like, yes, let me go write it and send you a thing. It's like back and forth. We produced it together, he directed it, I starred in it, and he's editing it. I'm a huge believer in the whole village concept that things like this, it definitely takes a whole community of people to make it, so that. Also, even the title, I wanted to make sure it was as Iranian American as possible because the title was originally Always, and that was his suggestion, he said, "Always." I took it and I said yes, and I also wanted to have Always, Azizam, so it's Always, Azizam. Azizam is the Persian word for my dear, my darling.

He now jokes with me, the fact that now people don't remember the always part, but everybody remembers the Azizam part. To me, that's an homage to my journey, to my family, to my queer Iranian family, that there is something out there, that that story has value, it has agency. When I get emails from queer kids from Iran saying, "Just knowing that someone like me is out there, you're proud, you're making your life, and you're outspoken about who you are and your community, that makes me feel that I can accomplish something.” Then that brings me back to what I said in the beginning, that I believe storytelling is a divine occupation for that reason, that it shows what needs to be seen, which is also... I mean, in America, all the banning books, I was going to say book burning, I mean I'm not that far off.

The banning of books and plays and all of that, and that shows you exactly what I'm talking about because if they weren't afraid of ideas, you don't need to ban books, you don't need to ban plays. That is the power of it, that it shows us what the world can be.

Nabra Nelson: We're so excited for that. We'll be looking out for that in all the festivals. I very, very much hope. Bazeed, if you want to talk, I know that we're very much running low on left time, but if you want to talk about some of your projects coming up so we can look forward to that, and then we'll close out.

Bazeed: Sure. Well, in my recent projects, I was very excited to get a commission from Noor Theater here in New York to write a play that I've been thinking about for several years that I'll finally get to kind of dig into this summer. The working title right now, and I think the title-title but we'll see is Sisters at Sunrise. It is a play that... I'm going to talk about the Scheherazade and One Thousand and One Nights frame story very quickly. I'm sure most people know it, but just to set up. In the frame story, the king walks in on his wife cheating on him, he makes a vow against all women and starts marrying one a night and murdering her in the morning and then taking the next one. Scheherazade is the storyteller who stops him by starting a story at nighttime and then kind of leaving him on a cliffhanger at dawn, so he keeps her alive for one more day.

In that frame story, her sister is often just there. She's the one who's like, "Scheherazade, tell us a story," to pass away the night, and then Scheherazade tells the story. Of course, in the One Thousand and One Nights we know we never hear anything else from Scheherazade except the bandits, the eagle that turns into a person, and then those fantastical tales. I was like, "Well, oh my God, what would it be like to follow these two sisters in the palace of a murderer where they both live for three and a half years in this kind of interesting captivity?" Then in my framing, it was Dunyazade who was supposed to go to the king and Scheherazade offers herself up instead, so there's also the sisterly resentment and guilt and all the things that are going to come from that little swap. There is that kind of going on. It's like a family tale.

Then, also there are sort of residences with the Arab Spring that are also part of that. Sisters at Sunrise, there will be a reading of it in the fall of 2023, I think probably around November, December, fall, winter I guess, something around there. I am also working on... I don't have any presentation details on this, but a project I'm excited to be working on also that will get a reading a little bit later in the year is Faggy Faafi Cairo Boy, which is my second full length play. Yeah, more details, TBD. But that one is about an immigrant who lives in New York returning to Cairo to see his father who is passed out in a coma in the hospital. Then, when he arrives, we realize that the father's soul is sort of present and can hear and see everything, but is not visible to his son. We sort of have the setup of him finding out about the son's queerness with that veil in-between them. It's a play that I wrote trying to answer the question, can homophobia survive the grave? Find out in Faggy Faafi Cairo Boy.

Nabra Nelson: So exciting. It was something we don't have time to talk about, which I really wanted to, but I'll just throw this out there, is that both of y'all are massage therapists. Talk about breaking out of boxes. I'm just so thrilled to hear this. Bazeed, I know you're just finishing up your certification in the next year. When we were talking earlier, Pooya, it was like, "I'm also a massage therapist." We were like, "What?" Everyone's mind exploded.

Bazeed: It's such a weird coincidence. It's so funny.

Pooya Mohseni: It's healing. We all need healing.

Bazeed: Pooya, do you still practice?

Pooya Mohseni: Here and there. One of the greatest parts of it, which I didn't say earlier is within the last few years I found this niche of transgender, nonconforming, nonbinary queer clients who were looking for massage, but they didn't want to go to places that they didn't feel safe or affirmed or judged or whatever. It's like that was just something that I hadn't thought about before until I came out of my practice, and my practice fully changed because most of my clients were cishet men. When I came out, it ended up being something that I had to do because I had come out obviously in my acting world, so I knew that if you search me, it's like the second article is the article that I had with Advocate or something. When I came out, I took control and I'm like, "I'm going to put that last nail in that coffin."

But what it opened up was, and I say it on my page, just like, "I'm a trans practitioner, and if that makes you uncomfortable, then I'm not the right person for you to go to." But I also offer a sliding scale to artists and queer clients because that's just my way of being a good co-community resident of sorts. I love that. That's something that I hadn't thought of. But when I get young trans or queer clients who've never had a massage, who have a lot of anxiety, who haven't had experience of touch that they're not afraid of, touch that is healing, that is nurturing in an environment that they feel safe, affirmed, accepted, and loved, and they just get to be themselves. It's just watching them bloom over the course of a few months or years, that is just such a privilege to see and to be able to be a tiny part of that.

We're all looking for things that makes life worthwhile. That indeed, if I can look back on it from my deathbed and look back and think that I brought healing, affirmation, and helped somebody be more at peace with who they are, if I was able to do that in a small way, then that is a good thing to have used one's life for.

Nabra Nelson: That is so beautiful.

Marina Johnson: Thank you so much. This has been so amazing. I mean, the work that you do both with massage and then your writing, your artistic practices, I'm so grateful for everything that you do, and I know that everyone listening is too. I can't wait to touch base with you after some of these other projects have come out too, and just, it's so exciting. Thank you.

Bazeed: Thank you so much, and nice to see you both again. It was nice to see your faces in pixels, if not person. Thank you so much for asking me to do this. Pooya, nice to be in the same room with you again.

Pooya Mohseni: Again, yes. When you said it, I actually remembered it was at an event that Rafael was also, as you said, the SWANA world, and then the queer SWANA world is kind of like all five people, but I consider that to be a privilege that I get to call you all colleagues and friends. As Bazeed was saying, thank you for the platform. Thank you for what you're doing, because this is how we tell the stories, this is how you change people's perception. I said it when we accepted the Obie for English. I said, "When you represent an otherwise marginalized group of people, a few things happen. The first thing is that the people themselves, that community itself, sees itself." It's almost like a child getting a sense of recognition, which then allows us to believe that it exists and that matters.

But then the second part of it is when you put the presentation, when people outside of that community also see that, then they feel more comfortable with that existence. It doesn't throw them off. It doesn't scare them because what are we afraid of, of the things we don't know? I mean, some people are just bigots and that's just them. But for most people, this idea that you represent an otherwise hidden... It's like sparse on the outside community, and hopefully in the long run that will just show them that they matter and the rest of the world that if they feel uncomfortable, that's okay. We all feel uncomfortable about many things, and yet we live and move forward.

Nabra Nelson: Beautiful way to end the episode. Thank you so, so much. Y'all have been so generous with your time. Oh my gosh.

Marina Johnson: This podcast is produced as a contribution to HowlRound Theatre Commons. You can find more episodes of Kunafa and Shay and other HowlRound podcasts by searching HowlRound wherever you find podcasts. If you loved this podcast, please post a rating and write a review on your platform of choice. This helps other people find us. You can also find a transcript for this episode along with a lot of other progressive and disruptive content on the HowlRound.com website. Have an idea for an exciting podcast essay or TV event the theatre community needs to hear? Visit HowlRound.com and contribute your ideas to the commons. Yalla, bye.

Nabra Nelson:

Yalla, bye.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here