An Informal Response to “Preaching to the Converted” by Tim Miller and David Román

In Tim Miller and David Román’s groundbreaking piece “Preaching to the Converted,” published in 1995 in Theatre Journal, they argue that queer art is best delivered by queer artists and best received by queer audiences. Essentially, preaching to the converted is the prime way for queer theatre artists to communicate and express themselves. Miller and Román suggest that, “arguing for preaching to the converted…(however much it historically has been deployed as derogatory) [works as] a descriptive essay for community-based, and often community-specific, lesbian and gay theatre…”

The phrase “preaching to the converted” works for the queer community specifically because of the subversive potential affinity that Miller/Román note between a queer performer recounting a particularly horrifying blowjob to a group of raging fags and dykes with a priest delivering an Easter homily to a congregation of well-to-do Catholics. Equating the two subverts the practice of the mass and roots the queer performance in ritual and mainstream. That root subconsciously alerts queer audiences that the theatre is a sacred place for refuge and spiritual connection; filling that hole left in previously religious individuals turned away or damned by the church. Queer purging and purification requires this preaching. Positing queer individuals must speak in code to one another for survival implies existence of a complex sign system for displaying concepts ranging from affection to sickness. That implicates both the performer and the audience in a dynamic conversation held in slight-of-hand, unseen by the heteronormative spectator. This conversation shatters the idea of a static audience.

I propose that we remain aware of our position as queer artists by understanding our cultural history and teaching as many other people about it as possible, starting with those in the family who haven’t heard the good word of acceptance, durability, and love.

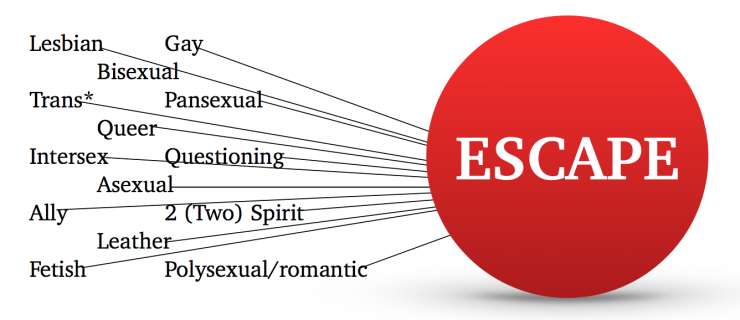

Present-day, this dynamic conversation mainly concerns identity and gender expression rather than sexual desire and romance, stemming from the sanctioned same-sex marriage and general acceptance of conventional homosexuality. Taylor Mac’s Hir or Kate Bornstein’s Hidden Agender are excellent examples of pieces built by, for, and near queers (to borrow sentiment from the Black arts movement). Many shifting identities have surfaced under the queer umbrella instigating a list of discovered identities (lovingly called “alphabet soup” by many queer theorists). To-date, the abbreviation is LGBTQQIPAA2LFP (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans*, Queer, Questioning, Intersex, Pansexual, Asexual, Ally, Two Spirit, Leather, Fetish, Polysexual/romantic).

This ever-expanding abbreviation is the dividing issue in queer art and activism. Currently, there are petitions to remove any letters standing in for gender with the argument that the foundation of the abbreviation is on sexuality. Contrary to that, many activists who are proponents of assimilation wish to erase difference with unilateral acceptance of the term “queer.” These debates are held on political and domestic fronts, with performance being the intersectional space between these spheres. In the face of these debates—whether they trigger frustration or excitement—one cannot solidly argue that queer art for solely (or mostly) queer audiences is static. That emotional response, or growing pains, within the queer space itself denotes a conversation. Moreover, this list grows towards a queer takeover of the entire alphabet, which would subvert the very letters the aforementioned priest uses to form words and statements for his Easter homily. Queer artists and audiences have remained dynamic and active in the face of this unstable and exciting identity crisis.

Now I speak to those in the family, to purposefully commit my own preaching to the converted in this piece. We, for a majority of American history, had to communicate to one another both our existence and our desires in code. That communication—operating with secrecy and exclusivity—was necessary to survive. Let us remain respectful of that history in our new-found golden age of queerness. I propose that we remain aware of our position as queer artists by understanding our cultural history and teaching as many other people about it as possible, starting with those in the family who haven’t heard the good word of acceptance, durability, and love. We know that we will never be able to separate ourselves from theatre, and I am in no way saying we should. So, let us accept this connection, accept ourselves, and accept each other.

Work Cited

Solomon, Alisa, and Framji Minwalla. "Preaching to the Converted by Tim Miller and David Román." The Queerest Art: Essays on Lesbian and Gay Theater. New York: New York UP, 2002. 220-51. Print.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I love looking back at this and in just over a year my language is already dated. Ha!

just as a passing reader - who happens to identify at gay in the old sense - i am constantly impressed with the ongoing redefinitions of sexuality, gender and societal placement. Are we still looking for identity in relation to the NORM? what was exciting when we were not normalized is that what ever our defining terms were, they were ours and not explicitly use to accommodate the mainstream thoughts or morals. The 21st century of personal identity and that power of individuals challenging who is "right" or correct is sometimes wearying - some days its just great to be yourself out in the world making art and theatre and performance. sadly i realize that the politics of that statement will infuriate many as well as comfort a number. Keep the conversation going and realize that any difference is good for the gander.

Hmm. An interesting read.

And if I am reading you right, you are suggesting that the word "queer" is used by "proponents of assimilation." Interesting. I identify as queer and have used "queer" (and understand "queer") to be distinctly anti-assimilationist. I see the term as politically resistant to mainstream media's recent acceptance of "gay" marriage and gay/lesbian culture. Rather than it being an erasure of difference, in my view the word speaks to an intersectional perspective, one that defies the commercialization and commodification of what is often the "legible" white, upper-middle class gay/lesbian image depicted in mainstream culture. I see the word queer as embracing that which is often left behind or left invisible: radical sexual practices, discomfiting or "offensive" identities (read: "flaming/flamboyant" gayness or "butch dyke"-ness), and poor people and people of color.

Thanks for this new perspective. I will need to think on this. I do NOT want my use of the word queer and my deep alignment/affinity for this identity to be perceived as pro-assimilation. I am decidedly not (I have some rather controversial/radical views on the whole marriage thing and a number of political issues). Perhaps I should re-think my language. Or perhaps I've misunderstood you altogether. But anyway, thanks for the read!

I was showcasing one particularly confusing use of the word that I had come in contact with recently (with some consistency). I think we need to keep queer around. However, we need to rework our feelings that using queer instantly means we are united, like a lot of queer-target marketing does. I believe queer is brandished by a vocal portion of the non-normative sexual and gender communities to elide difference. I think queer can be used for unity, but I don't see it done much right now. Some people gravitate towards factions. Some like transitive terms. Some like nothing at all. We need the options because we have strength in numbers.