Alas, Poor Diversity

a Case for The Jubilee

“The oppressed are those who are denied the right to make metaphors.”—Augusto Boal

As the discussion around the 2016 Oscars turned the spotlight of mainstream American media once more to race and the exclusion of minority voices from arts, I was reminded of the controversy in Los Angeles surrounding the Jubilee. The Jubilee is an initiative that invites theatres from all over the nation to pledge to produce only work by artists from marginalized populations for one year in 2020: plays by artists of color, women, LGBTQI, and disabled artists. It has divided the theatre community here in Los Angeles, with a vocal minority arguing that it’s discrimination against straight, white men. Their argument is that two wrongs don’t make a right; that the perpetuation of discriminatory tactics against one group is no way to create inclusivity for groups that are traditionally victims of discrimination. The naysayers demand that the word “only” be removed, as in the goal of every theatre producing “only work by [marginalized artists],” removing the one forceful commitment from an already voluntary call to action (read the full wording here).

The false analogy of ‘straight white male discrimination’ is that this group already has access to spaces of power and control that are not limited on the basis of who they happen to be.

But racism and discrimination exist in the United States in a historicized context that makes this hue and cry of “straight white male discrimination” as a civil rights issue an apples-to-oranges comparison. I argue that we need a Jubilee, a strong one with the language only.

We exist already in a politics of exclusion, in which diversity initiatives so often fail to create meaningful opportunities for marginalized communities, instead pushing them further into the margins through the illusion of inclusivity that reinforces stereotypes, denies agency, and allows marginalized groups to exist only in the context of dominant narratives. In one episode of Aziz Ansari’s show Master of None, Aziz deals with a network eager to cast a minority lead, but unable to even consider casting two Indian guys as leads for fear that audiences will think it’s an “Indian show.” Diversity initiatives that cast a broad net to try to represent all voices often slide dangerously into tokenism and the fetishization of difference, folding marginalized communities into the corners of neatly packaged dominant narratives.

What if, for just one year, it was all Indian guys? What if we painted a picture of a world where it wasn’t absurd to suggest that this could be normal, because it is the normal existence of a slice of America?

In place of what we usually think about as “diversity,” the Jubilee advocates what I call “protectionism”: the elevation of communities through the exclusion of other groups that allows the community on the inside to safely develop its voice. This is nothing new—see women’s writers’ circles. See gay bars. See historic theatres of color. Creating exclusionary spaces has always been a way to build capacity for the groups allowed to flourish without competition within those spaces.

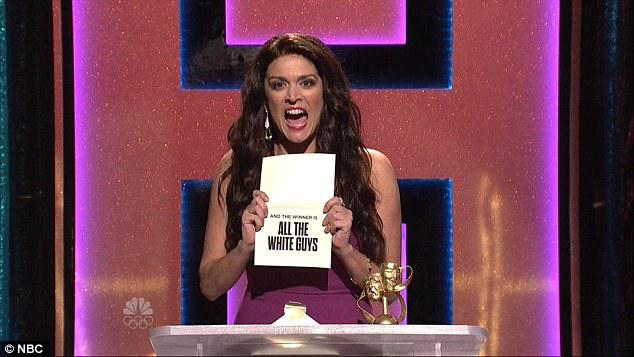

See Yale’s Skull and Bones society. See Wall Street. See, perhaps, the 2016 Academy Awards. The false analogy of “straight white male discrimination” is that this group already has access to spaces of power and control that are not limited on the basis of who they happen to be. This does not mean that individuals are automatically successful—just that they are not held back on the basis of their group identity. I argue that the best thing gatekeepers, can do for groups without this access is to open doors and get out of the way.

Photo by Tre'vell Anderson.

The classic artist’s retort to this line of thinking is that surely good art knows no color lines, that theatres should be a meritocracy with no space for affirmative action in the pursuit of artistic excellence. This is the “free market” analogy, where artists are competing on equal ground. Like free markets in economics, though, this great theory doesn’t hold up when reality isn’t providing a level playing field. There are more well-known plays by straight white men than any other group, and these playwrights will continue to be more widely produced not out of malice toward marginalized groups but because of ease and access.

I believe that we need strong incentives for historically excluded populations to flourish creating work, and there are both economic and political analogies to this situation that show how effective “protectionism” can be in place of “diversity.”

In response to the 80s Latin American debt crisis, Latin American countries were forced to open their doors to the free market by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. US companies rushed in to take advantage of free-market reforms so domestic production was opened to foreign competition and local industries suffered. In contrast, the “Asian Tigers,” the strictly controlled international trade economies of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan, built their internal capacity to the point where they could compete with the West in international markets. Only through excluding foreign competition for enough time to build local power were these economies able to be competitive

Another apt model can be found in German politics. Since the 1980s, German political parties have set quotas requiring a certain number of women to hold office. At first, this seemed to established parties like a terrible idea sure to get them unelected—legitimately, no women were qualified, and voters weren’t used to electing women. But with the quotas, a favorable supply-to-demand ratio for women politicians meant that suddenly women got qualified, fast. Voters got used to ticking their names on boxes. Early trailblazers created pathways and mentorship opportunities for the next generation of female politicos. After only a few decades, Germany developed a pool of female candidates with solid records and strong backing who were electable on their own merit regardless of their gender. This was only possible because of near-draconian affirmative action to correct historical imbalances that otherwise like would have perpetuated themselves into perpetuity otherwise. Having proven the effectiveness of this type of policy in government, Germany passed a related law in 2015 for private companies requiring female leadership at a rate of 30% (the magic number for policy influence), following similar laws in Norway, France, Spain, and the Netherlands. While quotas and affirmative action remain contested terms in the US, they are tried-and-true methods and increasing the representation of marginalized groups in much of the rest of the world.

The Jubilee is hardly as radical as either analogy—it doesn’t require long-term investment or change, but it does model what is possible, to give theatres and audiences practice, even just for one year, in investing in art beyond their comfort zone and dominant narrative. In the theatre, we have the same concerns as these historical German parties—what if marginalized playwrights aren’t as good, and what if they can’t draw an audience? But what if making it work is as simple as giving it a chance? I suggest, as with so many things, that the answers are time and money. With access to time and resources, somehow the playing field seems to level out.

In researching this article, however, a friend shared with me the concern of a number of Los Angeles institutions that historically serve marginalized communities. They have been doing what the Jubilee proposes for years—it’s central to their mission—and they are worried that dominant-group theatres are going to swoop in and co-opt their audiences, their funders, and the work that they have been steadily building in a one-year publicity grab. So many theatres exist on the precipice of financial ruin that if, even for one year, the funding and audiences go elsewhere, it’s a very real possibility that the historic mainstays of marginalized communities could go bankrupt. And if the Jubilee is successful in securing marginalized artists more lucrative, mainstream opportunities, they may indeed have to sacrifice smaller opportunities within their communities, impoverishing their artistic homes.

An effort to mainstream marginalized artists runs the risk of destroying the institutions of “protectionism” that have historically fostered them. This is the Catch-22 of the Jubilee.

The challenge and hope is that the Committee of the Jubilee will find ways for the pledged theatres to acknowledge, celebrate, and elevate theatres that have been fulfilling the mission of the Jubilee for years already. That it will be a megaphone for existing voices and not supplant them with new voices. I remain optimistic that mainstreaming artists will have positive effects for marginalized theatres, and that, when dominant-group theatres go back to producing their usual work, some of the new artists from the Jubilee year will be included, and audiences who now know these artists will seek out other places they are being produced.

An effort to mainstream marginalized artists runs the risk of destroying the institutions of ‘protectionism’ that have historically fostered them. This is the Catch-22 of the Jubilee.

It seems unlikely that a rising tide will raise all ships equally here, but these concerns are mitigated by the fact that they will happen in such a small way that they may not even be statistically significant. A one-year initiative carried out through a non-binding voluntary resolution seems unlikely to change the face of American theatre. Because the Jubilee exists in the context of American society that provides disproportionate opportunity to straight, white men, it will mostly benefit straight, white men despite its seemingly radical “protectionist” policies. It will be dominant-group theatres that get media attention and new funding for doing something new, and their audiences that will swell with new populations. The system is still going to benefit the people it benefits, no surprise there.

So, with these issues, is the Jubilee still worthwhile?

If only for promoting these discussions on a national scale, I say yes. Bernie Sanders may not win the Democratic nomination, but he can shift the discussion so that his proposals and some policies make it through regardless. Like most activism, I argue, the Jubilee is problematic, but the alternative is to do nothing. Furthermore, the way the Jubilee’s shift in model from “diversity” to “protectionism” makes it an exciting pilot for a large number of mainstream theatres to try a new tactic—one that historic theatres serving marginalized groups have been championing for years.

I am looking forward to the Jubilee and to more years of dialogue and figuring things out.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

My dream for the Jubilee is that it increases awareness of everyone, that it inspires and changes everyone--from artists to audience to funders, at all economic levels and different producing models. Because the attendance lists will be broad, and should be wide-sweeping. We all have something to be gained from this social experiment no matter how deep we participate. But the more we commit to fully participating and inviting others to do so, the more we all have to gain in the end. Call me crazy, but that's why I am on board in support of the Jubilee. Thanks for your writing.

Hi Rachel, well put. I agree that the success of the initiative will depend on the depth of participation of participating organizations - how much theatres actually seek partnerships and change their seasons.

Brian, you are right to raise the concern that during the Jubilee year, mainstream institutions will suck up all of the oxygen and starve existing theaters that serve marginalized communities of needed grant monies and audiences. One of the ways this can be avoided is if mainstream theaters partner and collaborate with those who are already doing the work that Jubilee is intended to celebrate and promote. That way, underrepresented artists and plays by writers of color can be introduced to new audiences, while strengthening the finances of marginalized theaters.

Thanks for posting, Dan! I love the idea of partnerships and know East West Players has been really successful in cultivating these in order to broaden its base and grow its reach while staying true to mission - how this has been achieved could be an interesting follow-up article if you'd be interested in having a chat about it!

There's another great example of how this kind of "redressing the cultural balance/creating the space to flourish" model works, and it's right next door to you. A few decades ago, Canada instituted Canadian Content regulations for radio: a certain percentage of the music on the air had to come from Canadian musicians. Commercial stations howled with rage, and Canadians had to suffer through some awful songs (like anything from Glass Tiger) just to fill out the time slots. But guess what? Over time, extraordinary musicians in all genres were able to get airplay, audiences, album sales. The beneficiaries were not just the Céline Dion and Shania Twain mainstream, but the now-thriving indie scenes across the country (which also produce their share of K'Naan or Arcade Fire-style breakout successes). Distribution models have changed in the digital age, but the culture is ensconced and strong and our bands no longer have to move south just to be heard.

Contrast that with our poor beleaguered film industry. Years ago, the government tried to set up a similar system where a (tiny) percentage of Canadian movie theatre screens would be reserved for Canadian films. This time, Hollywood, which considers our movie theatres to be as much a U.S. territory as Puerto Rico, howled bloody murder, and got Congress to threaten trade sanctions against things like Canadian lumber (!!!) Jack Valenti and the MPAA won, and now we have all these incredible filmmakers whose films are lucky to run for one week in Toronto or Vancouver... Until they get tired of the fight for audiences of 2,000 and start directing in the States. (An exception to this is the French-speaking province of Québec, where cultural nationalism has resulted in a much healthier scene full of popular and well-supported artists: Xavier Dolan, of Adele-video fame, is just the tip of the iceberg).

I don't know how to solve the problems of the small theatres you allude to, who have been honourably fighting for diversity, and fear losing audience to this initiative. But they cannot continue to be the only option for the bulk of writers of colour. Poverty and marginality sometimes go hand in hand with artistic greatness, but they neither produce it or sustain it. The question is, if playwrights can find larger audiences and more of a living wage for the work... is there a way these companies can also benefit?

Hi Leanna, thanks for providing another example - I knew about Canadian radio but hadn't thought about it in this context, I think it's absolutely relevant and has been really inspiring to see how that nudge has elevated musical life up north. I think Dan's comment earlier is right in proposing institutional partnerships as a way to create win-wins for companies as the artists that they've fostered gain new opportunities under the Jubilee.

Very well said! Jubilee needs to keep happening.

At first blush, I liked the idea of devoting a year to producing work by marginalized voices. The more I think about it, the more I agree that it may not do what it should to raise the profiles of theatres that have this has their mission all the time.

What would be great would be to see some of these larger, established companies who represent the cultural majority lend their space and clout to the existing theatres who have always produced plays outside of the mainstream. Even if they didn't do this for a year, committing to the promotion of work written by "others" and produced by the same for, say, every other production would make a huge difference.

Thanks for commenting JasFaulkner, much appreciated. I agree that institutional partnerships may well be the way forward with the Jubilee, though they are not (yet!) enshrined in its language. I love the idea that, beyond representing marginalized voices for a year, this initiative has the potential to bridge the gap between heavily resourced mainstream institutions and all sorts of marginalized-community-serving companies.

Heh. Compare and contrast over the threatened lawsuit over HAMILTON casting.

Ah @gwangung:disqus I know! I wrote this article during the Oscars controversy, and then it was posted the DAY the Hamilton blow-up happened. Talk about timing!

I loved this article -- thank you. It's all so well said. Great stuff.

Thanks @myakagan:disqus , much appreciated!