Day by Day

Finding the Voices of Deaf Leadership on Stage

“So how do Deaf people sing?” I am often asked that question and my answer has been given more depth by the recent commercial successes featuring Deaf culture and American Sign Language (ASL) which have exposed more and more people to the value of Deaf culture and community. The recent Deaf West production of Spring Awakening on Broadway as well as the long running television show Switched at Birth, has created interest from a hearing community that often sees the disability rather than the benefit of a highly visual community with a refined communication skill. As a scholar of leadership I can also see how theatre can serve as a living laboratory with which to observe and study the cultural development of Deaf leadership in an era when we all seem to be continuously dealing with the heated debate of social justice versus the desire to privilege emotional pain and offended feelings. Casting hearing actors in a role written for a deaf person has been determined a “no-no.” But what about the reverse—casting Deaf actors in a musical intended for hearing, singing actors? As it turns out most playwrights seem to be curious about the translation process and are open to the idea, but that still leaves us with the process of representing a blended community, diverse in ethnicity and varied in communication.

My direction of a musical theatre production of the Tebelak and Schwartz musical Godspell using a Deaf and hearing cast is the most recent opportunity I have had to observe Deaf leadership in action while rehearsing a theatre piece. I came to the Deaf community early. My Grandmother was deaf, and so my love and feeling of belonging to the Deaf community is attached to my feelings for her. I attended Antioch University’s program for Leadership and Change through the Arts and devoted my Ph.D. dissertation to exploring the topic of building bridges between Deaf and hearing cultures through performance arts.

Imagine a group of people in a circle. As one person feels moved, confident, and skilled enough to address a problem they step into the circle. When their part of the process is finished they step back and wait. Soon another person steps in to take the project to the next level. …To a hearing person’s eye this can appear to be structureless or inefficient; and yet the result is often highly refined.

My resulting qualitative research and Pulitzer Prize nominated theatrical production provided a foundation to continue to observe and explore this phenomenon. What I found was that Deaf leadership (even when placed in a hierarchical setting) tends to be collaborative. Imagine a group of people in a circle. As one person feels moved, confident, and skilled enough to address a problem they step into the circle. When their part of the process is finished they step back and wait. Soon another person steps in to take the project to the next level. When done, they too step out and this pattern continues until the project is completed. To a hearing person’s eye this can appear to be structureless or inefficient; and yet, from my experience participating in Deaf productions, organizations, and projects I can say the result is often highly refined.

I call this approach to leadership Collective Individualism (Haggerty 2007). There is not a single leader; instead, there is often a group—a collective of sorts. The typical rehearsal structure for a theatrical production is a comfortable setting for this type of leadership to emerge, if the director is willing to be open to allowing it to happen.

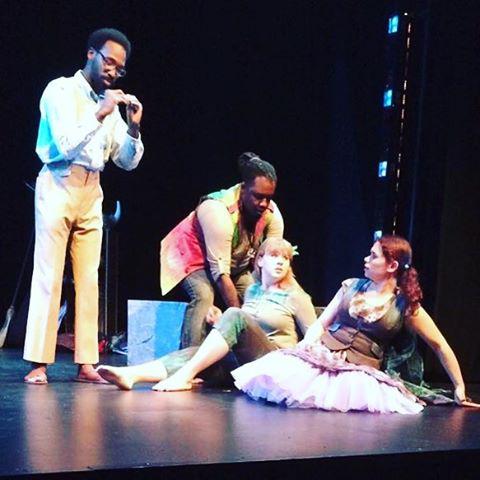

This production of Godspell produced at the National Technical Institute of The Deaf in their lab theatre, toured to the local LORT Theater here in Rochester, NY (Geva Theater), and then moved to New York City working in collaboration with the IRT Theater and performing at the Lexington School for the Deaf this past spring. This was a collaborative production, even on an administrative level. It is an accepted fact that Deaf culture emerges from a community effort (Gannon, 1981). Theatre is, by its very nature, a creative community. By analyzing the rehearsal and performance process with elements from several leadership theorists, a common theme appears. The influential leadership of the student/actors who have a strong self-identity and clearly exhibit more stage skills often outweighs positional leadership of working with hearing collaborators who are placed in positions of power—like a director. The process for observing Deaf leadership in this article will use the rehearsal process for Godspell (a musical performance piece that focuses on community building through the use of biblical parables) to mirror the typical formation of Deaf community with its mix of ethnicity (deafness occurs in all cultures and countries), it’s blend of mainstream hearing culture while maintaining a purity of Deaf culture linguistically, and its focus on the ensemble rather than the principle players.

For some practical examples of how these approaches to leadership play out, let’s take a peek into rehearsal. One of our actors is from Malaysia and knows traditional dance forms. He is also enamored with the Indian Bollywood style of mixing Indian dance with American musical theatre. So when our choreographer was working on creating the dance movement to match the song “Light of the World,” the actor stepped forward and offered to show his idea for using Malaysian dance elements mixed with musical theatre style. When the group showed interest in his idea, he created the dance first with his hearing partner, then showed the group the movement. The group approved and worked with increased enthusiasm and a stronger sense of ownership on that piece than they did on some of the other pieces that were dictated by the positional leader in the form of the choreographer.

The Artistic Application and Results

Careful consideration of Deaf community internal conflicts that arose was crucial to the success of the production. We collectively discussed and monitored both internal issues in the cast and audience issues with how we were playing with language and cultural blend. As the hearing director, I needed to be aware that my perspective and bias might trigger members of the Deaf community who may have political problems with a musical theatre piece done with Deaf actors, as Deaf actors being asked to do music and perform “as if hearing,” might be considered a kind of auditory blackface.

Music has long been thought to be a hearing culture form of artistic expression (Bragg 2001). However, newer generations have had access to music videos with captioning for as long as they can remember. Musical theatre pieces performed in ASL or with Deaf performers are becoming more and more an acceptable way to present a model of how the Deaf and hearing cultures can work collectively (Meath-Lang 2001). This functioning model of bi-cultural cooperation would have many more applications in our global world and deserves further study on its own.

However, for the purpose of this article, descriptions of how the hearing and Deaf actors choose to work with each other are of most interest. For many hearing performers the challenge to use an added skill or performance element is an attractive challenge. Musical theatre actors are, in particular, physical performers able to sing, dance and act, often simultaneously. However, they are not used to the incredibly difficult task of serving two audiences with a variety of different language needs. The Deaf actors are the more skilled performers for this particular environment and quickly rise to the challenge of teaching their hearing companions the ropes. In the Deaf community you have a wide range of communication styles. ASL is the purest and most admired, but there are varying levels of fluency even among the Deaf (Gannon 1981). ASL needs to be taught and so Hard of Hearing actors who were raised in an oral tradition (using lip reading and English literacy) sign with a different “accent” than a person who has been surrounded by Deaf fluent signers their whole life (Adler 1970). Hearing interpreters also use a range of sign styles from Simultaneous Communication (SimCom) to pure ASL. Imagine trying to speak Italian and English at the same time (SimCom). Just thinking about it can make your head hurt, and because we cannot voice two spoken languages at the same time it is hard to make an understandable comparison to SimCom. Yet, when members of the Deaf community who have clear speech try to include everyone into a conversation they tend to use SimCom. SimCom seems to become a linguistic bridge of communication when an individual’s natural urge is to become a bridge between cultures. The linguistic result varies and is probably better compared to Spanglish (Spanish and English mixed in a dialect). Each of these different communication styles implies a different accent or background for a character and although not all of these forms of using sign are the height of artistry, they are highly interesting when depicting the full range of the community, much in the same way a hearing community will have a polyglot of accents all understandable (although not equally as clear) in English. The Deaf members who are experienced performers tend to be highly versatile in all these different communication styles, while the hearing people are not. Actors have a natural interest in “trying on” different characters and an accent is one of the easiest ways into that understanding and representation. Thus the rehearsal process tends to begin with the Deaf actors taking leadership positions as translation from English to sign takes place.

These same Deaf actors step back and let their hearing companions step forward when music, timing, pitch, and interpretation of music is discussed. As an individual felt the impulse to step forward and lead in the daily warm-up exercises before the show, the group reinforced their behavior by becoming unquestioning followers. When the next individual wished to step forward the original leader stepped back to allow them the room and respect to emerge as a leader. This behavior was not a new skill acquired in rehearsal; it’s much older habit developed as a member of the Deaf community and copied by the hearing actors. This could be used as a physical metaphor for how Deaf leadership is shared in the process of production.

As Deaf leadership becomes a valued part of the discussion on leadership and more theatrical productions using Deaf actors find commercial success, it supports the perspective that taking cultural risks which breakdown the barriers between communities is a sign of strength for the continuing influence of Deaf culture and literature in the mainstream.

The continuing growth and popularity of Deaf performers and productions using ASL provide a basis for analysis using the structure of a theatrical production which can naturally bring out leadership qualities. Those qualities are expressed in Deaf culture in a relational theme that is consistent across several different theories on leadership. In this way not only can a Deaf leadership “voice” be heard by those outside of the community, but also, I dare say, it sings!

Theatre appears to be particularly useful for Deaf leadership observation. Any gathering or organized group has the potential to allow for the emergence of a leader, but theatre in particular provides several key features that are helpful when looking for Deaf leadership. Storytelling is an essential element of ASL communication. The nature of ASL as a language encourages the speaker to take on the body language or character of the person being spoken of, rather than the English language structure of “he said, she said.” This type of communication is theatre in a nutshell. Theatre production also has a defined time frame and a clear common goal which is approached by self-selected people who are highly motivated to make the project a success. Theatre has long been known to be the most collaborative of arts, embracing strong personalities and strong types of people. In order to see a collaborative form of leadership emerge, the environment that a typical theatre rehearsal process provides is a comfortable setting matching common elements in both the mainstream hearing culture and the Deaf culture to create a natural bridge for collective individualism to thrive. As Deaf leadership becomes a valued part of the discussion on leadership and more theatrical productions using Deaf actors find commercial success, it creates a spark of hope that can build a flame. This flame can further illuminate the perspective that taking cultural risks which breakdown the barriers between communities might be dangerous, for sure; but, it’s also a sign of strength for the continuing influence of Deaf culture and literature in the mainstream, possibly allowing even more of us to sing together.

References

Bragg, L. (Ed.). 2001. “Deaf World.” New York, NY: New York University Press.

Gannon, J. R. 1981. “Deaf Heritage, A Narrative History of Deaf America,” Washington, DC: National Association of the Deaf.

Goleman, D. 2002. “Primal Leadership, Realizing the power of emotional intelligence.” Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

Haggerty, L. 2007. “Adjusting the Margins: A dissertation on Deaf leadership,” Ohio Leadership Archives.

Haggerty, L. 2007. “Storytelling and Leadership in the Deaf Community,” ADARA pages 39–64

Lane, H. 1992. “The Mask Of Benevolence: Disabling the Deaf Community.” New York, Alfred A Knopf.

Managrubang. 1993. “Characteristics of leaders: Deaf administrators and managers in employment.”

Meath-Lang, B. 2002. “Dramatic Interactions: Theatre Work and the Formation of Learning Communities.” American Annals of the Deaf 142(no.2): 99–100.

Additional resources

http://www.rit.edu/ntid/deaftheatre/

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I love the idea of combining hearing and non hearing people together to collaborate for a production. It would be really cool if hearing and non hearing people could do a movement/devise piece, I would be interested in that. Theatre is a great outlet for anything and everything. And for the non hearing it’s an opportunity of leadership, it’s a lesson the hearing can take away from it. I love that. But I like how there isn’t just one leader, the whole group are leaders. That’s what theatre is all about, being a community and creating together. I never realized the issue when working with non hearing people when asked to perform as hearing, it is very offensive.