Black Women Have Theorized Everything

This week, HowlRound presents #BLKARTS Presents: Black Womyn Going Dark!, a co-curated series that explores the ancestry and legacy of black womyn in the arts featuring contemporary artists who create in multiple communities across the United States. Co-curators Erin Michelle Washington of Soul Center/ #BLKARTS, ATL and Deanna Downes of Deanna Downes Creative Consulting seek to engage a creative community of black womyn around questions including: What new/old ways are we creating/exercising to reach new or intended audiences? How are we creating access to the research of ourselves and our ancestry? This series is the beginning of a project that aims to address these issues for, by, and with black womyn artists. You will hear from artists across multiple disciplines using multimedia, writing, sound scores, visual arts, and other avenues in which we can expand our storytelling. These works and these womyn expand, define, and give framework for our contemporary experience of living in and through art.

—Deanna Downes and Erin Michelle Washington

The conversation below is between two Black feminist cultural producers. We, Sola Bamis and Tia-Simone Gardner, read and worked through the ideas in Lorraine Hansberry’s The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window (1963) and Lynn Nottage’s Sweat (2017). What we hope is that the love we have for these two artists structures the conversation and critiques that we had of their work, and also that the love and respect we have for each other as Black feminist artists and intellectuals is made clear.

Initially it was difficult for us to find points of dialogue between these two playwrights’ work, but through our conversation we returned time and time again to the ways that both Hansberry and Nottage brought us back to the unresolvable conditions of living under what bell hooks terms a structure of “heteronormative, imperialist, capitalist, white supremacist, patriarchy.” In contrast to Hansberry’s Sidney Brustein, which takes its point of entry into this structure from the position of the white male liberal intellectual, Nottage’s Sweat weaves together an analysis of contemporary struggles of capitalist domination through the voices of a group of laborers in a small manufacturing town in Pennsylvania. Nottage deftly walks us through conditions of mass incarceration, US job outsourcing, and anti-immigrant fervor, while tracing the ways in which all of these things are rooted in structures of white supremacy and patriarchy.

Hansberry and Nottage brought us back to the unresolvable conditions of living under what bell hooks terms a structure of ‘heteronormative, imperialist, capitalist, white supremacist, patriarchy.’

We do not want to conflate Hansberry and Nottage’s voices into a single, smooth articulation of Black women’s cultural production, but we do want to ask ourselves how Black womanhood has shaped their perspectives. How might their work instruct us, as Black women cultural producers, in how to create polyvocal texts, how to enter into the ethos and pathos of another who lives in a reality so far from our own, as in the case of two white male protagonists: Sidney, in Hansberry’s work and Stan, in Nottage’s? One of our guiding truths is that Black women have theorized everything because Black women have been placed so often in the unique position of having to think for others and anticipate the myriad forms that oppression may take.

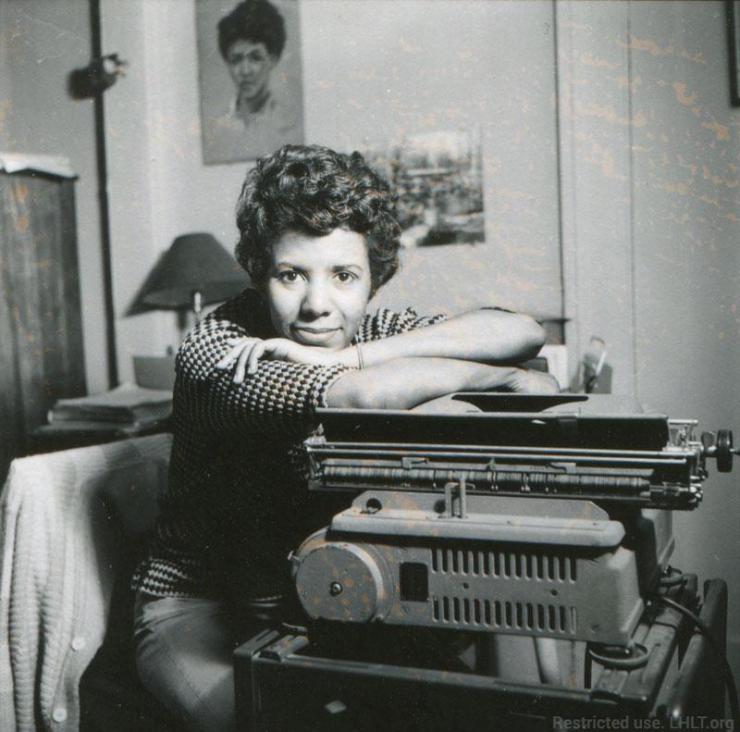

Lorraine Hansberry's record as the first African-American female playwright to be produced on Broadway should serve as more than trivia in or at the intersection of one's Black, Women's, or Theatre History studies. The seminal Broadway premiere of A Raisin in the Sun in 1959 set the stage (pun absolutely intended) for the magnification of both Black and female voices in contemporary theatre. And while the struggle for full inclusion in mainstream theatre arts has been so enduring that many of its purveyors and professionals wonder whether much has changed still, one must acknowledge the significant contribution of Hansberry's work not only to the Black Arts movement but to contemporary theatre as a whole.

Her stellar range is demonstrated in the tremendous shift in voice she makes from Raisin, a family drama with an all-Black cast, to the only other play of hers produced on Broadway during her lifetime, The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window, a portrait of the existential crises threatening Manhattan white liberals. This multivocality in her writing, a feature which has indeed solidified her legacy as one of our great dramatic writers of the twentieth century, is also apparent in the work of the latest Black female playwright to be produced on Broadway, Lynn Nottage. In Sweat, she uses her deft voice to bring life to a diverse group of factory workers responding to the evisceration of manufacturing jobs in Reading, PA. The authors posit that both artists employ their identities as Black women to articulate a meaningful and multifaceted perspective, speaking honestly and authoritatively from the intersection of race, gender, and class.

It came as no surprise to learn that reviews to the production of The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window were largely mixed. As Black female artists and intellectuals ourselves, we are attuned to the establishment's tendency to misunderstand, and thus underestimate, our ability to convey truth from a perspective different than our own. Joi Gresham, director of the Lorraine Hansberry Literary Trust and daughter of Robert Nemiroff, Hansberry's ex-husband, remarked, “There was a tremendous reactive force from critics wanting to see a sequel to Raisin. People were just not willing to see the play she had written.” Never mind that Hansberry belonged, in earnest, to the community of Greenwich Village hipsters she depicted in Sidney Brustein's, and that the issues the characters faced in their art-making, political engagement, and strivings for personal happiness were similar to those she struggled against. The sardonic tone she uses in the description of this world, “The setting is Greenwich Village, New York city—the preferred habitat of many who fancy revolt, or at least detachment from the social order that surrounds us,” indicates that it's a cultural and intellectual space she calls to from the inside. For those critics who were unwilling or unable to accept that idea, the thrilling accuracy of her depiction be damned, what she had to say didn't matter as much as she was a Black woman who had the audacity to say it. What they failed to recognize, though, is that it was indeed her Blackness, and her femaleness, and her queerness that made the characterizations in the play spot on. Her understanding of the varying forms of systematic oppression is so profound, it informs every relationship. There are personal costs to political choices, and the power dynamics presented mirror those in the social structure that the protagonist, Sidney Brustein, most benefits from, yet deeply laments. In effect, Hansberry subverts the white male gaze to expose the hypocrisy of white liberalism.

The life that she so expertly instills in Sidney is full of the humanity usually granted to (and sometimes only reserved for) white male protagonists in media. Political inclinations notwithstanding, he is presented as a Founding Father—a bastion of logical thought and free speech, and charged with the duty of teaching those around him. He is described as, “in his late thirties and inclined to no category of dress whatsoever…It is not an affectation; he does not care.” Sidney is as neutral as white men come and his style, better yet, his refusal to achieve a style, is reflective of that. He is further established as the neutral and didactic authority when he lambasts compassion in his review of Alton’s writing, instructing his friend, “Don’t venerate, don’t celebrate, don’t hallow out what you take to be the human spirit. Keep your conscience to yourself.” In the same moment, he very subtly engages the audience with a smile, then declares, in reference to the publication he's just acquired, “I am the proud owner, editor, publisher, guiding light.” The authority he places in himself with that statement, however, is belied by his next gesture, where he completely breaks the fourth wall: “His eyes are now only for the audience; scanning our reaction with a wet-lipped savoring.” This action, which signals to his desire for approval, dilutes Sidney's self-claimed power as the “guiding light.” Hansberry is telling us that, yes, the window is his, but the play is hers.

From then on, his white male voice is imbued with the irony of Black feminist thought, and the reader/viewer understands the piece for the powerful critique that it is. In Poetry Is Not a Luxury, famed Black feminist Audre Lorde writes, “The white fathers told us: I think therefore I am. The Black mother within each of us—the poet—whispers in our dream: I feel therefore I can be free.” With this understanding of what Black feminist thought requires and illuminates, we see Sidney for who he is, not who he thinks he is. His singularity (“There’s gotta be people like me somewhere, don’t there?) becomes self-righteousness, his derision for compassion and psychoanalysis demonstrates his lack of true self-awareness, and the fissures in his facade as the creative, magnanimous, ever-neutral white male sage deepen. This dissolution is paralleled in the events of the play as his wife, Iris, for whom he's been “lover, father, universe, god,” decides to leave, his drinking behavior escalates, and the pain of his ulcer intensifies from aggravation to agony. As the tragedy of the narrative, the suicide of Iris's troubled sister Gloria, approaches, we find Sidney asleep, numbed by alcohol, medication, and privilege. It is the untimely and unsettling loss of his sister-in-law, coupled with the disappointment by his politician friend, Wally O'Hara, that finally forces Sidney to take a position and fight, and we spend the last moments with him and Iris grieving. Hansberry highlights this breakdown of the attachment to personal privilege and the failure of political engagement to reveal the tenuousness of the unengaged white liberal community. In her treatment of Sidney, she shows how the hypocrisy of their desire to be politically benevolent yet maintain their race, gender and/or class privilege creates the conditions for a populist, corporate-owned, charismatic leader to emerge.

It is as though Nottage picks up where Hansberry left off, using her voice to examine the personal, human cost of waging class warfare.

This played out very truthfully in The Sign in Sidney Brustein's Window, and indeed as it has throughout history. We've seen the proliferation of this type of leader over time and how his shortsightedness and thirst for power has led to racialized neoliberalism, a shrinking middle-class, and, the prison industrial complex, conditions that set the scene for Lynn Nottage's Sweat. It is as though Nottage picks up where Hansberry left off, using her voice to examine the personal, human cost of waging class warfare.

It is worth noting that Ms. Hansberry made her transition the same night that Sidney Brustein's closed on Broadway, January 12, 1965. We comment on this fact, again, not as a matter of trivia, but because we believe that in the play she foresees her passing from the physical world and the passing of her legacy. Even among liberal intellectuals, she chooses not to depict a world that has resolved the problem of a white supremacist-heteropatriarchal-capitalist social structure. The tragedies are personal and we are instructed to “Weep. That is the first thing: to let ourselves feel again...Then tomorrow, we shall make something strong of this sorrow...” As this structure persists and the personal costs of hegemony are endured, Black women continue to make something strong of this moral breakdown. They observe from the intersections at which they reside, and keenly translate the depth of their intuitions to the characters that populate their work.

With this sharp observational power, Sweat explores the implosion of American manufacturing towns by looking at the lives and experiences of nine laborers. Nottage’s play is structured around critical political moments: the 2000 election of George W. Bush, and the 2008 election of Barack Obama, and how these moments brought about renewed interest in the conditions of American citizenship. With this political stage, Nottage chronicles the decline of Reading, Pennsylvania, through the lives of political actors who are simultaneously hypervisible and invisible in this national dialogue, the worker. Using a nonlinear chronology, Nottage begins at a critical moment in the loaded space, a meeting between a parole officer, Evan, and a parolee, Chris. Working backwards, then again forwards, through time, Nottage pushes the interactions and dialogue of the play toward a sharp rendering of the play’s subject, what could be characterized as the anxieties of whiteness, that linger so casually throughout the relationships she describes. In a series of episodic events that largely take place in the confines of a local bar, we watch as the the fear and anger that have been boiling between the characters ruptures into the play’s climactic moment, a decisive argument that returns us to the play’s beginning, the event that brings us to the meeting in the parole officer’s office.

At best, today's American laborer is disposable and unheard, manipulated by the whims of a largely invisible market, helmed by white male patriarchs lacking any hint of benevolence. Lynn Nottage illuminates the unheard voices of this laboring town with lucidity, empathy, and compassion. In a timely maneuver, however, Nottage’s focus on the American working-class poses a sharp contrast to Hansberry’s portrayal of the lives of the white liberal activist-intellectuals of her time. While the characters in Sweat are hyperaware of the structures of power being acted on them, for example they relay concerns over NAFTA and labor outsourcing, Nottage is careful to reflect a particular problem of laboring people. That is, she exposes the ways that white supremacy and capitalism seek to systematically drain the time, creativity, and energies of working people, keeping us so busy with the need to survive and stay sane that mass organizing feels impossible. And while certainly some will see this as a point of critique, raising questions about agency and resistance, it is important to remember that the voices of this play emerged from interviews and conversations with people who lived these lives, that rather than write a romantic story of the ultimate triumph of the people against corporations, Nottage writes the hard truths of struggle and loss as they were recounted to her. Unapologetically so.

An aspect of the play that gave us pause, was the figure of Stan, the bar owner whose role as patriarch space-holder give literal and metaphorical place for the action of the play to unfold. Similar to Sidney, Stan’s character is the benevolent white male, who holds the least precarious position of all. His bar is where everyone will eventually come to mend themselves, or make amends to one another. Even as the town’s economy declines, as Cynthia loses her house, and her son Jason goes to prison, Stan’s bar remains intact. And it is Stan’s injury that ultimately closes the play. Stan is a consistent presence, unlike the invisible corporate bosses who are slowly dismantling the wage work available in Reading. So we have to ask, what does his presence do for the play as a whole? What questions, problems, cautions does he raise for the audience that are not or cannot be raised by other characters in the play like, Cynthia, a Black woman who is promoted just before the situation at the plant becomes dire, or Tracey, her friend, a white woman, who comes to resent Cynthia and anyone else she feels subordinates her, or Oscar, the Dominican busboy who works for Stan?

Nottage allows us to reflect on the space and time we are living in; the rich characters she has developed reflect a number of lived realities of racism, sexism, classism, mass incarceration, addiction and so much more. Black women have theorized everything. Lynn Nottage and Lorraine Hansberry demonstrate the exhaustive imagination and intelligence that Black female playwrights have and continue to bring to the stage. As writers they illuminate the uncomfortable and unvoiced parts of humanness that remind us how limited we are. As artists-intellectuals they bring to life what Cherríe Moraga terms “theory in the flesh,” the embodied experiences of people who live at the intersections of racism and patriarchy. Through their work they transform the stage into a space of radical epistemic labor, a space of knowing, speaking, and reflecting.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you for this analysis and collaborative effort. It comes across so cogently and clearly and is inspiring for collaborative writing and collective creation. This series in general is awesome. This is the second installment right?

Maybe this isn't the place for this question, but I am wondering what your thoughts are on how theory in the arts can help translate into the will to organize that you describe Nottage's play depicting as missing in the workers.

Working at The Graduate Center CUNY near the phd theatre department here, I am often asking myself this question in general, especially as I see my colleagues get so far down the rabbit hole of examination and explanation that I can barely understand the discussion of my own work...

I'm not saying this essay does that at all, to be clear. But it's such a poignant effort, I wanted to ask your opinions.

How does our intellectual engagement in our art and artists provide a road map to activism as people? Is that the point? If not, what is it?