Let’s Get Lost

Can Rock Tell a Story Onstage?

Between the 2009 debut of the television show Glee and last year’s hit Broadway show Hamilton, musical theatre nerds have come out in full bloom, safely protected within pop cultural niches that draw likeminded fans. But why are they nerds? As composer/performer Dave Malloy put it in his 2011 HowlRound article, “A Slushy in the Face: Musical Theater Music and the Uncool,” musical theatre is “still decidedly uncool. Why is this?”

Malloy has since done more than his part to bring fashion to the form. From the chamber-thriller Ghost Quartet, born at New York’s funky Bushwick Starr, to his exploration into the interior of classical pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff in Preludes, Malloy has been busting at the seams of what defines musical theatre for nearly a decade. Last November, his electro-pop musical Natasha, Pierre & the Great Comet of 1812 debuted on Broadway, upending theatrical norms both in terms of audience experience as well as sound.

“The American musical has a particular vocal and compositional sound, and we all know it when we hear it,” Rob Weinert-Kendt wrote in his 2013 American Theatre article, “It’s Better With a Band: Musical Theatre’s Next Tune.” But, “it’s not what most of us choose to listen to on our iPods, on our Pandora stations, in concert halls or on our party playlists,” Weinert-Kendt said nicely. “Musical theatre has been genre-fied in a way that is a complete disservice to the form,” composer César Alvarez stated more bluntly in the same article.

As a music lover, I try to find what’s interesting in any type of music, but I struggle with the musical theatre sound. It’s one I associate with squeaky clean, bland vocals, overblown orchestration, and general earnestness. There, I said it.

Love It or Hate It

The musical theatre genre Alvarez refers to is one of those “love it or hate it” things. I personally tend toward the latter sentiment. As a music lover, I try to find what’s interesting in any type of music, but I struggle with the musical theatre sound. It’s one I associate with squeaky clean, bland vocals, overblown orchestration, and general earnestness. There, I said it.

It’s an issue for me, because as a music lover who’s also a director/choreographer and deviser, the contradiction between my love of music and theatre and my dislike of musical theatre has often left me in the lurch. Raised on dance, dance theatre, and straight theatre, I grew up seeing the value of music to make theatrical moments transcendent—though musical theatre itself was foreign to me. By the time I got around to discovering it, I found that somehow music specifically made for theatre and actor-singers was, to me, not just not-transcendent, but often downright annoying. I wondered, how do you combine music and theatre in a way that doesn’t have that musical theatre sound?

What Is That Sound Anyway?

Musical theatre composition and execution is subject to the “orthodoxy of diction, projection, and extroversion” cited by Malloy, which can be traced back to training and culture:

The worst musical theatre singers adhere to a very learned, imitative, uniform style that has evolved over years of fusing classic Broadway singing with jazz, rock, and pop. It’s a style that is usually the result of years of training in over-articulating, over-enunciating, and over-emoting, presumably to insure that the words are heard and understood.

Orthodoxy of enunciation, then, is really the well-meaning product of insuring lyrics serve the story of a musical. But I’d go one step further to say that annoying sound is the sound of anxiety. The anxiety of not wanting to leave your audience behind.

Once I started incorporating live music into my own original works, I realized two things: 1) It’s loud! and 2) That truism about the audience being happier when they know what’s coming also applies when a song is playing. Perhaps this enslavement to vocal orthodoxy had come about for a good reason.

The Contradiction between Rock Music and Story

Rock is a mood, an ethos, an experience. Rock music breaks rules, creating a temporary world out of sound and feeling. Cool is, by definition, seemingly effortless. Therefore, cool rock music at its core goes against what we consider the musical theatre genre to be: polished, perfect. Think of early American rock and roll, like the burn of Chuck Berry, a punk anthem like “Sheena is a Punk Rocker” by the Ramones, or a sophisticated track like Radiohead’s “Everything in Its Right Place.” The only thing they have in common is that each is a complete world unto itself. Could you describe what life is like in that world? Could you repeat back every word of the lyrics? Do you need to in order to be moved?

Song lyrics generally don’t stand up to being analyzed, nor do music lovers demand they make logical sense. It’s unfair to expect rock lyrics to bear the weight of too much narrative; lyrics carry sound as much as or more than meaning. Look at a lyric too hard and it disappears. In The New York Times’ 2010 article “Broadway Rocks. Get Over It,” Jon Pareles wrote, “rock operas that came across as complete when they were just songs on albums—with listeners imagining action and filling in gaps and back stories—still leave theatregoers complaining that the characters are hollow.”

As such, rock musicals are often criticized for having weak books—i.e., a lame story that creates thinly veiled excuses for the next song. American Idiot, based on the music of Green Day, died several times for the sins of the rock musical. But American Idiot relies on the songs as portraits of America and offers characters that are contained within the lyrics’ poetic landscapes. The story encompasses a string of events that trace a dramatic arc for a few of those characters, but isn’t trying to use the text to get the audience invested in their stories. The buy-in comes through the more complete worlds of the songs.

Like dance, rock suggests a different theatrical language, a different frequency of transmission to communicate its meaning. Tommy isn’t trying to tell a story in a straight-ahead way, any more than Martha Graham, Mia Michaels, or Ohad Naharin do (though those choreographers all use story elements). Rather than an operatic recitative where lines of text are sung, rock relies on an associative, sometimes hallucinatory quality. In I’m Not There, the 2007 movie by Todd Haynes based on the life of Bob Dylan, Haynes uses multiple actors and film looks to portray a variety of time periods and creative sides of Dylan. Dylan’s music shifts and changes, dreamlike, while the story employs a cast of potentially unrelated characters. It may be hard to track but it makes its own kind of sense.

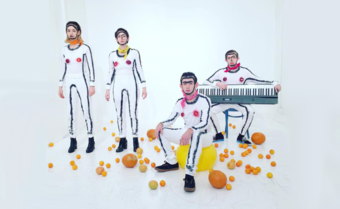

My own experiments in rock/folk for theatre have yielded the discovery that what is gold on a music track can be kryptonite to your play. Long jams, while great at a concert, can flummox the director’s need to build tension second by second. As a choreographer, I often have trouble setting a dance break to a groove: there’s no beginning, middle, or end. Classical music can offer its own challenges of duration. Rachmaninoff’s cascades can easily drown you if you don’t know what each one of them means, and why it’s different than the last (full disclosure: like Malloy, I also co-created an original music theatre piece using Rachmaninoff compositions; The Snowstorm, pictured here). Training existing music to a narrative, I started to see why A Chorus Line and Into the Woods both have long, unwieldy passages that mount tension in the show, but sound strange out of context. These ungrooveable and sometimes even pompous musical structures are actually doing the heavy lifting to keep the action of the play going.

Reinventing the American Musical

In 2013 American Theatre proclaimed: “the American musical looks and sounds more like a jam session between indie bands and theatre artists.” Weinert-Kendt cited Alvarez’s Futurity as a prime example, played by his band, the Lisps. The New York Times critic Charles Isherwood called it “some of the most lovely and inventive music you can hear on a New York stage right now.” If Futurity “often feels more like a staged oratorio with some heaping spoonfuls of dialogue thrown in than a fully fleshed-out musical,” then perhaps the new musical doesn’t look or smell like a musical at all. As the musical format evolves, it can include plays with songs handed down from English music hall like Peter and the Starcatcher and David Grieg’s Midsummer. It can wrap its long arms around Pixies band member Frank Black (aka Black Francis) and his Bluefinger. Musicals can mean Young Jean Lee’s We’re Gonna Die with electronica band Future Wife as well as Hadestown, an Anaïs Mitchell album-turned-play. In other words, the new music theatre can hold all kinds of Frankensteins.

In reinventing the musical theatre experience, perhaps we should start with architecture. In 2011 Malloy wrote, “Theatrical venues have all these trappings that are so bad for music—they’re the antithesis of the musical experience. The politeness, the seats, you can’t have drink or food in there, the quiet.” Each of Great Comet’s venues has been transformed into a supper club where snacks and drinks are for sale. Moreover, actors can be found in the aisles or in audience members’ laps.

Perhaps the next groundbreaking scores will come from ensembles, either through devised practice or collaboration, rather than lone-wolf composers or the classic composer-lyricist team.

Here Lies Love is another musical whose immersive aesthetic is fundamental to its core—that and the compositional punch of David Byrne and Fatboy Slim working in tandem to deliver bona fide rock. Byrne has joined the likes of David Bowie, U2, Serj Tankian, (of the band System of a Down), and Sara Bareilles in lending star power to live music’s uncool cousin. Innovation may not only come from importing celebrity rock composers to musical theatre, but from creating diversity in the pool of composers trained for musical theatre. “We need composers and singers that come from rock clubs, cabarets, basements, not undergraduate musical theatre programs,” Malloy groused. “[M]ost rock musical theatre composers sound like they are composing inside a bubble, without ever having played in rock bands or spent any time immersed in the music they are imitating.”

Perhaps the next groundbreaking scores will come from ensembles, either through devised practice or collaboration, rather than lone-wolf composers or the classic composer-lyricist team. Martin Lowe, the Tony Award-winning orchestrator of the Irish-folk score of Once, started the task of scoring by transcribing the songs from the 2006 movie soundtrack recordings. Then, he invited an extraordinary group of musicians to experiment with the songs, arriving at arrangements that incorporated the instruments his performers most loved to play. The musician’s exploration was key to finalizing the score.

The uneasy tension between rock’s quest for freedom and the demands of narrative will no doubt continue to generate new strains of music and theatre co-existing onstage. In my work, I am happy to keep chasing after an ideal like rock or soul, forever trying to grasp something that is ultimately ungraspable. Not grasping it means there will always be another piece to create that might capture the spirit of the music a bit better. I look for new ways to pair music and theatre that actively pull from musical influences traditionally outside the musical theatre genre including classical, folk, R&B, and singer-songwriter genres. I look for ways that spoken text can interact with music and movement, places where nonverbal storytelling may be scored. I add movement to plays where it isn’t specified, necessitating the creation of music, in shows from Shakespeare to new work. I look for places where the staggering power of song can enrich a narrative and bring down the house. I continue to seek out a breadth of cultural and historical influence in the stories we choose to portray onstage in order to expand the definition of what “the American musical” can actually be. I look for ways to lift up the human experience with the power of live music.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

And interestingly, the Tony voters picked a traditional (albeit excellent) musical and score over a truly innovative one, so I don't think 21st century Broadway rock is going away anytime soon.

great article - thank you

"The musical theatre genre Alvarez refers to is one of those 'love it or

hate it' things. I personally tend toward the latter sentiment. As a

music lover, I try to find what’s interesting in any type of music, but I

struggle with the musical theatre sound. It’s one I associate with

squeaky clean, bland vocals, overblown orchestration, and general

earnestness."

As a huge, long-time fan of traditional musical theater ("Guys and Dolls", "Oklahoma", and so forth) as well as the original "Jesus Christ Superstar" (with the lead singer from "Deep Purple") and some other rock-influenced musicals, I strongly disagree with most of this article.

I don't think the issue is non-rock versus rock but good versus bad. Alas, youth (except for "nerds") tends to gravitate towards rock, whether good or bad, so long as it seems sufficiently anti-establishment.

(And I've lived long enough to notice that it is most often these types who, upon arriving at middle age, find religion and turn into fire and brimstone types who [in order to make up for their youthful indescretions] tell the rest of us that we are all going to go to hell if we don't believe everything their pastor or preacher says.)

"There, I said it."

Good job! Very smart essay. You seem to be suggesting a turning point in musical theatre. I hope you're right.

Thanks Parfy!