Coney Island’s Fantastical History

What Love Never Dies Leaves Out

I recently saw the US national tour of Love Never Dies in Boston, MA. Love Never Dies delivers a spectacle, but it does so while erasing Coney Island’s ebullient freakshow history. The disabled performers that made Coney Island a world-famous attraction are written out.

For a musical owing its location to the disabled community, Love Never Dies is decidedly remiss in incorporating the community.

In an Entertainment Weekly article, Andrew Lloyd Webber explained his decision to stage Love Never Dies, his sequel to The Phantom of the Opera, in the infamous New York sideshow getaway Coney Island, saying:

The obvious thing would be if [the Phantom] were an outcast from France that he would come to America. And then the one place a freak or somebody who was frightening, abnormal in one sense, would be recognized as completely normal, no questions asked, would have been Coney Island. And the more I looked at the old footage of Coney Island and what really, really happened there I thought it would make a wonderful area in which to set the show.

I was disappointed to find that Lloyd Webber excluded the freak performers he credits as inspiration. He appropriated their culture without representing the people who created it.

History of Coney Island

Coney Island started small. An attraction called Lilliputia opened in 1904: a functioning city for little people with a saloon, theatre, and fire brigade. By 1911, the Samuel W. Gumpertz had gathered little people, persons with medical deformities, and other unusual persons to the New York seashore to live and work at his Dreamland Circus Sideshow. Gone were the days of P.T. Barnum showcasing indentured performers for his own profit. The disabled community made a healthy living while choosing when and where the public stared at them. Until Dreamland closed in the 1930s, it was a place where “The Other” had a home.

Other popular historical sights at Coney Island at this time included Josephene Myrtle Corbin, a four-legged woman, Alice Elizabeth Doherty, the bearded lady, and Mary Ann Bevan, a woman with acromegaly. Dr. Martin Couney ran a baby incubator exhibit at Luna Park which brought modern medical science to impoverished families. Americans could gawk at “barbarian” tribesmen from across the world. All of these performers were in New York by choice. Performers such as Bevan considered public exhibition their only career option. Public display was the price they paid for a comfortable living.

The Coney Island freakshows died out by 1950. Many performers were successfully diagnosed with treatable conditions. Milroy disease, Sturge-Weber syndrome, orthopedic conditions, conjoined siblings, and other physical irregularities were curable or preventable. Some claim that the rise of television and the fall of vaudeville led to the freakshow’s demise. Others say that humanity finally acknowledged the inherent depravity behind exhibiting the disabled for profit. The novelty of viewing the physically irregular for pleasure had finally worn off.

Representation in Love Never Dies

Love Never Dies takes place in 1907, three years into the freakshow’s East Coast rise in popularity. For a musical owing its location to the disabled community, Love Never Dies is decidedly remiss in incorporating the community. We are offered mere tokens: a few musical numbers briefly mention oddities, and only “The Beauty Underneath" uses freak attractions in its staging.

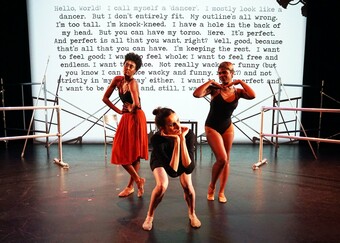

In this number, Phantom entreats young Gustave to look beyond conventions to see beauty in the abnormal and ugly. They walk the Phantom’s lair singing “Do you find yourself beguiled/By the dangerous and wild/Do you feed on the need/For the beauty underneath.” Mirrored structures rotate around them while dancers in gruesome masks writhe. The mirrored structures are cages and reveal sideshow freaks sitting within them. The freaks include an albino indigenous person (played by a white man), a polymeliac Black man, a living mermaid, and a man with feet-long fingernails.

This staging implies that the caged performers are kept there at the Phantom’s whims—they are slaves, and not among Coney Island’s paid able-bodied performers. In choosing this, it seems that the original choreographers and director do not view these characters as human. Historical photos from Coney Island show performers uncaged and unfettered. Love Never Dies has them caged in translucent coffins. They have neither agency nor representation. The famed performers of Coney Island and the current disabled community deserve much better from such a massive entertainment platform.

The disabled community resided in Coney Island for decades. It is on their backs that the tourist attraction came to flourish.

Casting

Fleck is one of the Phantom’s observant minions. She is the tokenized personification of the disabled community…but only sometimes. Fleck was originated in London by non-dwarf actor, Niamh Perry. Emma J. Hawkins, the first little person to play the role, performed in the 2011 Australian production. Despite the musical’s iterations across the globe, a little person wasn’t cast again until Love Never Dies played in Germany. Lauren Barrand and Sandra Maria Germann were cast there in 2015. Currently, Katrina Kemp artfully plays Fleck in the current US tour. Troika Entertainment did not cast any other noticeably disabled actors in its Boston performances.

This production history tells us that Fleck is played by a differently abled person when it is convenient to casting directors. Even in attempting lip-service by compacting all of Coney Island’s disabled community into one secondary role, casting agents still fail to respect the disabled community.

The inconsistent casting of a little person expresses insensitivity to auditioning actors. For example, casting Websites like StageAgent don’t account for the physical requirements of the role. When performance rights are finally released, professional and community theatres will assume it is safe to cast Fleck with an able-bodied actor regardless of current casting. Disabled artists will have to content with able-bodied artists for Fleck.

The disabled community resided in Coney Island for decades. It is on their backs that the tourist attraction came to flourish. It is incredibly problematic that Lloyd Webber, his co-creators, designers, casting directors, and other artists should ignore the community that made 1900s Coney Island famous. Love Never Dies is ableist. Without its freaks, geeks, and other differently abled performers, Coney Island would have been merely another sandy boardwalk.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Great article. Though it's a different medium, I didn't want to see The Greatest Showman because P.T. Barnum exploited differences, not celebrated them.

Agreed. The Greatest Showman also erased much of the disabled community's influence on Barnum. It turned Barnum into an abled savior rather than revealed Barnum's hypocrisy.

There is a documentary on youtube on him. It's so sad to think about the ancient ways abled individuals oppressed disabled individuals. The circus or the mental institution.