The devising Spanish company Grumelot, founded in 2005 by Carlota Gaviño, Javier Lara, and Iñigo Rodríguez-Claro, has been at the cutting edge of theatrical performance during the pandemic. In June, their Delicuescente Eva explored simultaneous streaming and filmed performance: live actors performed before a few physically distanced spectators at Madrid’s Teatro de la Abadía as the show was simultaneously filmed by multiple cameras and streamed online for a much broader audience. With Game Over, their most recent offering, they expand the limits of digital theatre beyond the merely remedial. A profound exploration of storytelling across platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Spotify, Game Over suggests what theatre might look like in a multi-modal future.

Distanced Devotion

Grumelot’s Game Over Brings Us Closer

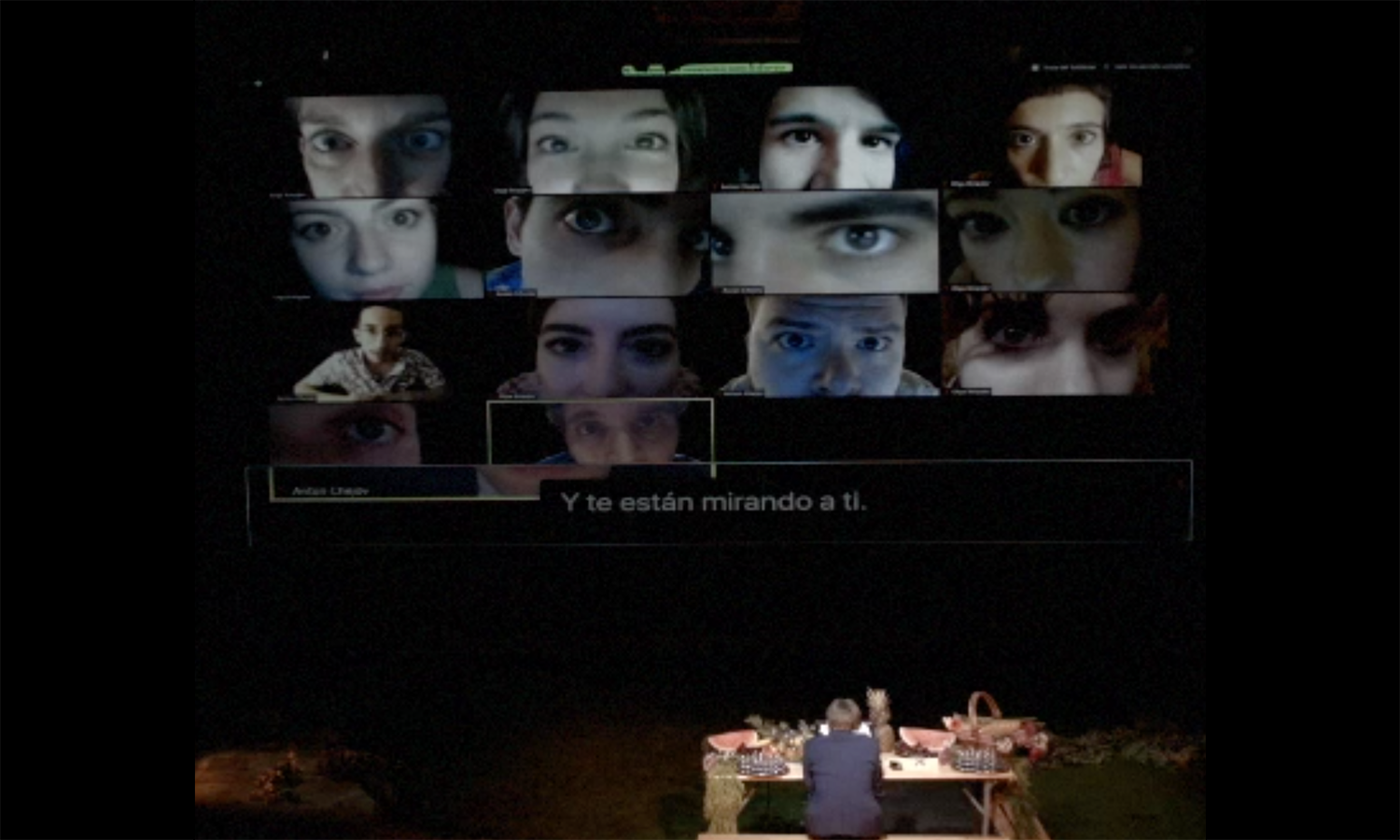

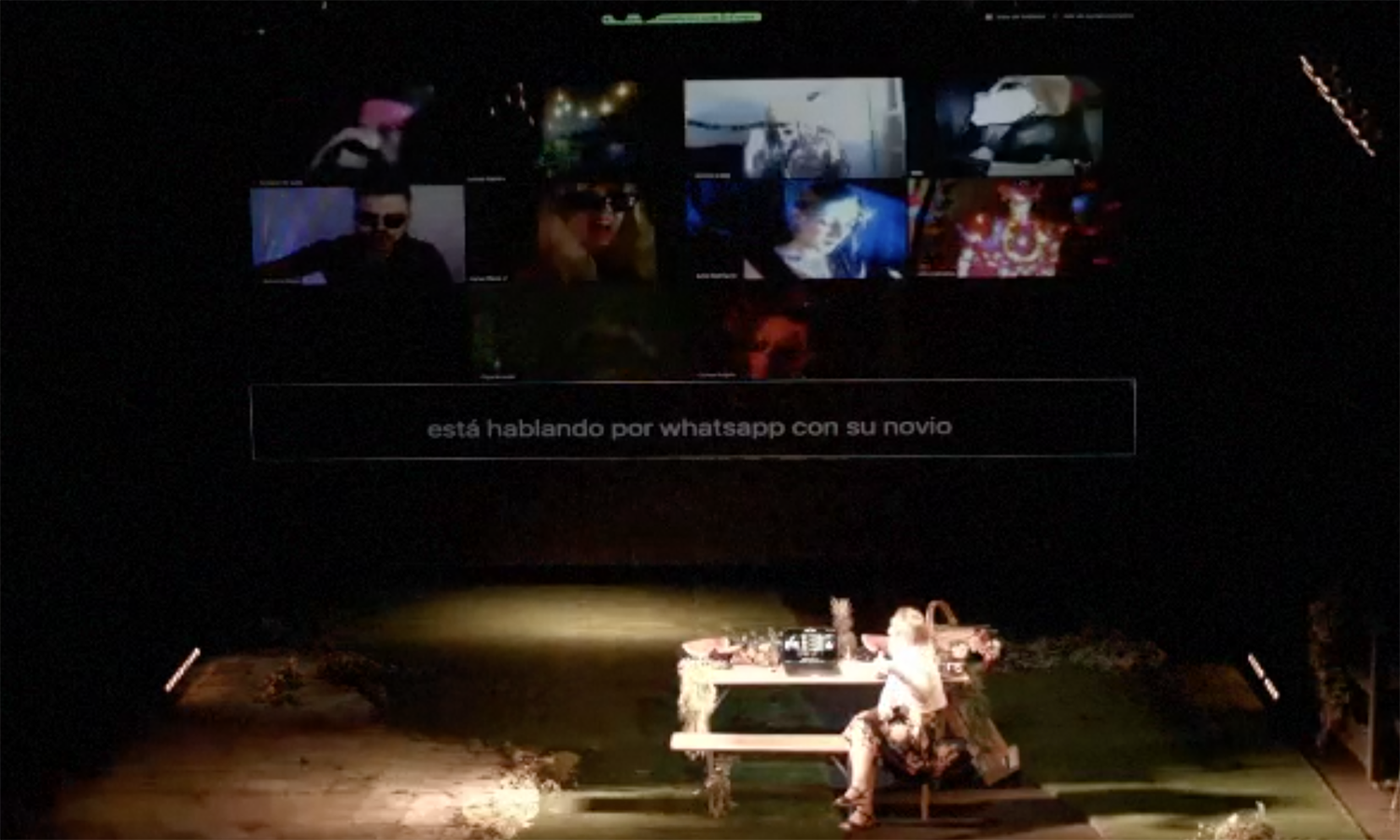

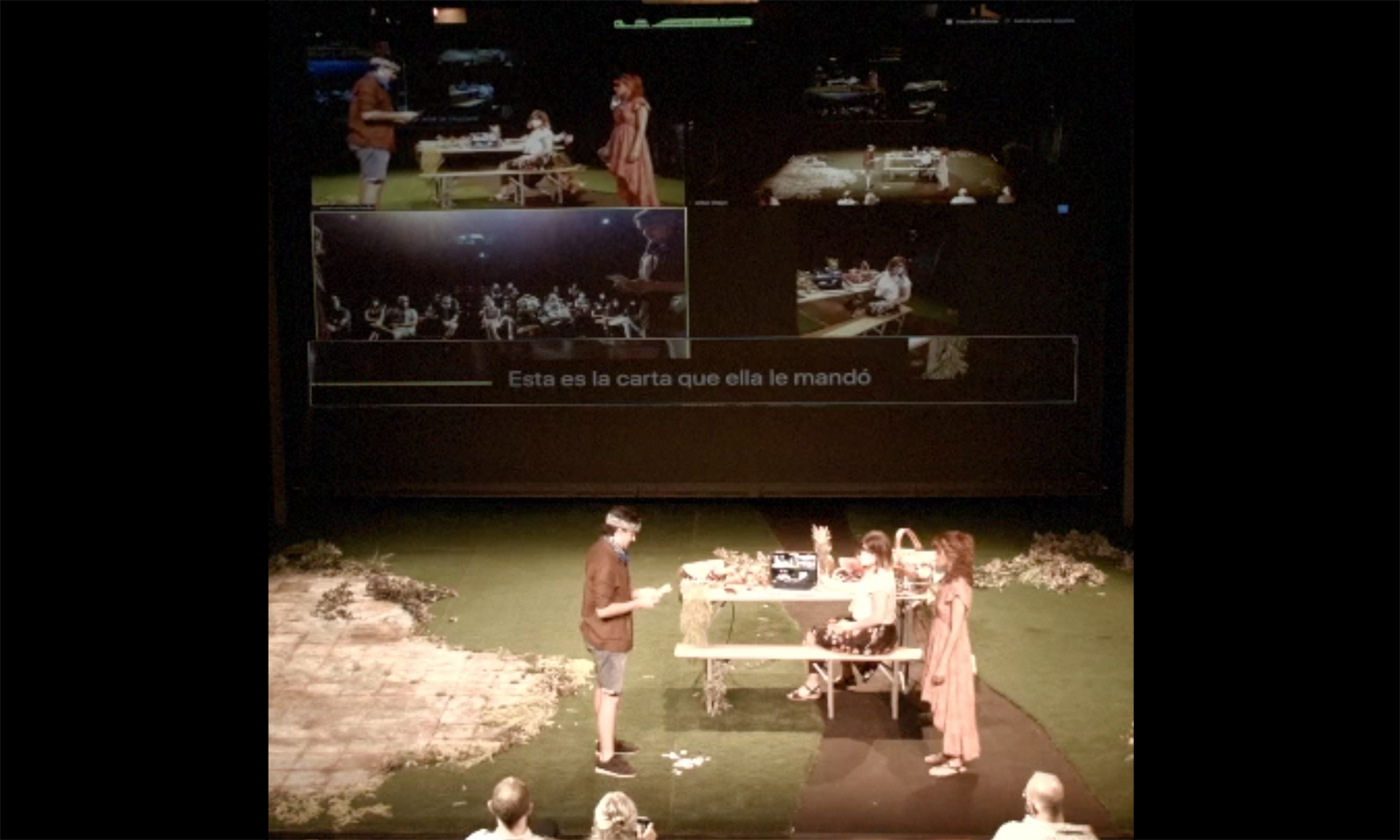

A screen capture from the recording of Game Over at the Teatro de la Abadía, Madrid, where the multi-platform piece was viewed live by a reduced in-person audience, courtesy Carlota Gaviño, Grumelot.

Based on the love letters between Anton Chekhov and the actor Olga Knipper, whom he married a few years before his death in 1904, Game Over explores the possibilities of human connection across impossible distances, when one party is facing life-threatening illness (sound familiar?). Knipper lived in Moscow, where she was one of the original company members of Stanislavski’s Moscow Art Theatre and played many of Chekhov’s key female roles, including Masha in the first production of Three Sisters. Meanwhile, Chekhov, suffering from the tuberculosis that would kill him, lived in Yalta (Crimea) for its warmer climate. If the 1147 miles that separated the two would still prove daunting today, in the era of WhatsApp and Zoom, at the turn of the twentieth century they were enormously challenging, especially for Knipper. Her letters are full of playful longing and entreaties for Chekhov to come to her—a grueling journey that would take weeks, if not months. Though distance proved endlessly frustrating, it also produced the wonderful letters. Knipper continued to write even after she learned of Chekhov’s death, as though she could not bear to say goodbye to that heightened channel of communication between them.

Perhaps because so many of us treat the phone as an extension of our psyches, the sense of intimacy and immediacy was striking.

To devise Game Over, Grumelot held a workshop for young actors, selecting fourteen for a five-week online exploration in June and early July. As Gaviño notes, “We were interested in how technology, which is so quotidian for us and already part of our lives, could help us create a virtual multi-platform experience.” Grumelot’s work often involves superimposed theatrical modes, with the spectators taking an active role by choosing where to focus their attention. For Game Over, Gaviño explains, they wanted to see “how many platforms could be used at once to establish the most intimate of connections with the spectator.” The resulting piece is devised theatre reimagined for multiple platforms, and also a new kind of immersive theatre under lockdown, which an audience of sixty to seventy viewers from across the world experienced on 4 July 2020.

Game Over, which was primarily in Spanish, with some fragments of the letters between Anton and Olga read in French, announced itself with instructions on my WhatsApp: I should log into the Zoom at the appointed meeting time, and also monitor my phone for information. Links to a webpage, Instagram, YouTube channel, and Spotify made it clear that no one platform would contain the entire story. (At this point, I called in reinforcements, in the form of my theatrical teenager and his gadgets, to try to keep track of everything that was going on. Only mild eye-rolling ensued.)

A screen capture from the recording of Game Over at the Teatro de la Abadía, Madrid, where the multi-platform piece was viewed live by a reduced in-person audience, courtesy Carlota Gaviño, Grumelot.

The ironically named programa de mano that I first received on WhatsApp hinted at the complex playfulness of Game Over. A screen recording captured the toggling of an anxious lover on a phone—from WhatsApp to photos to Sim City. Just by viewing the program, I was suddenly deep in a text exchange, perusing short voice messages full of longing, scrolling through lonely photos on the beach, and checking a lover’s location on a map. While the program was prerecorded, it reproduced the immediacy of typing and correcting oneself, changing one’s mind about how best to engage an absent lover, and so forth. Perhaps because so many of us treat the phone as an extension of our psyches, the sense of intimacy and immediacy was striking. Yet the intensity of the intimacies on display kept it from feeling voyeuristic—this was not a show put on to titillate viewers.

Even before the piece began, the WhatsApp narrative took on our nostalgia for the theatre, with brief texts recreating the experience, like “You are now entering the theatre” and “You look around as you find your seat and try to recognize some familiar face,” and a voice recording from the usher.

Once on Zoom, we were introduced to the company. The sheer number of platforms was now matched by the multiple actors playing Antons and Olgas as they negotiated their various relationships at a distance. Playfully holding up acetate slides with impressive Chekhovian beards over their faces, the actors invited a reflection on the very idea of character, which was explored throughout: How many different versions of Anton and Olga can we conceive of, or recreate? Live captioning on Zoom, stuttering across the bottom of the screen, suggested writing processes—letters or telegrams—as the actors brought the lovers’ longing, ardor, and doubt to life. Antons and Olgas danced, took showers, ran through Berlin, and strolled on the beach in a richly impressionistic live sequence that emphasized simultaneity of experience, however far apart they were geographically. The live performances occasionally gave way to prerecorded fake ads that reflected on how capitalism and religion both take advantage of our need for connection and escape.

There was unguarded wonder on people’s faces as they encountered whimsical missives that echoed the symbolism of the piece.

The moments of more traditional shared viewership were interspersed with audience participation and choice. At one point, viewers were briefly invited into individual Zoom breakout rooms. In mine, an actor led me through a process of character construction, with echoes of Stanislavski and a distinctly Chekhovian feel:

You’ve always liked cherries. When you were five, you ran away from home and spent four hours in the tree in the garden. You stuffed yourself with cherries… When you were thirteen you tried smoking for the first time. You did not like it. At sixteen you fell in love with Ania. At eighteen, with Ivan….

While some of us were creating characters in breakout rooms, others were witnessing Olga and Anton’s engagement, or dancing along with Olga in her dressing room, or receiving a phone call in which Anton first declared his love to her.

Once reconvened on Zoom, viewers were instructed to turn on their own video and were led through a Pirandellian meditation on what it might mean to be someone else’s character or creation. Beyond the metadramatic charm of these moments, they deepened the piece’s reflection on the relationship between an author and the actor for whom he wrote some of his most famous characters.

A screen capture from the recording of Game Over at the Teatro de la Abadía, Madrid, where the multi-platform piece was viewed live by a reduced in-person audience, courtesy Carlota Gaviño, Grumelot.

The audience was also on display, with cameras on, as some of us finally opened letters that Grumelot had previously sent in the mail—an analog dimension of the piece that was unfortunately unavailable to those watching from across the ocean. There was unguarded wonder on people’s faces as they encountered whimsical missives that echoed the symbolism of the piece, and held them up for all to see. There is pleasure, too, we were all reminded, in what is not immediately available.

The WhatsApp messages continued throughout the performance, occasionally pointing to a parallel Instagram Live, on which one of the Olgas fought over the phone with her Anton. A song list on Spotify added to the nostalgic mood.

Narrative structure was effectively multiplied and undone in the service of a deeper dive. To be sure, as with so many tragedies, we knew already that this story would not end well. And despite the misleadingly teleological title, narrative progression was hardly the point of Game Over. Instead, Grumelot and their deft collaborators, designers Itxaso Larrinaga, Iara Solano, and Alex Peña, offered a paradoxical version of immersive theatre at a distance: not site-specific, though it was about location; not VR-enabled, though it made ample use of the technology on everyone’s gadgets to get into our heads and under our skin. Self-aware yet emotionally engaging, even moving, Game Over reflected on how we both make contact and make up for it, as hyperconnectivity meets a time of pandemic.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Planned before covidtimes home quarantining? I'd love to see the flowchart of storyline moving through decision points and social media options!