The remarkable anti-war play The Last Days of Mankind, created by satirist Karl Kraus a century ago, unfortunately needs to be discussed, read, and staged again and again. It offers the theatre community an opportunity to respond with artistry, imagination, and boldness to the current war in Ukraine which threatens to expand across Europe and involve nuclear weapons. The war there has raised anew the specter of human self-extinction introduced by Kraus’s play in 1922.

Other wars go on across the planet, too—some civil and some far from civil. I would like to see theatre artists respond to these hostilities with a centenary celebration of Kraus's satire, much as The Lysistrata Project (2003) launched a myriad of widely dispersed artistic responses to the threat of war in the Middle East by offering readings and adaptations of Aristophanes’ Old Comedy about war and peace. New renderings of The Last Days of Mankind would permit theatre audiences to share the fiercely comic and provocative indignation of Kraus's epic scenes of war's planners, its profiteers, victims and apologists.

Kraus's play is admittedly not as well-known as the satire of Aristophanes. Its huge cast of characters and 588 page-length have challenged directors and actors in the past. Brecht wrote about wanting to stage it in tandem with his Schweik in the Second World War but ultimately did not. Italian director Luca Ronconi reportedly spent millions on his 1990 production in Turin. The cost of a full production could be prohibitive—but then billions are spent on warfare these days. Kraus's play would cost far less to stage, especially if it is cut or adapted. In any case, the immensity of the threats posed by current wars and weapons of mass destruction merit the imaginative and massive response this play allows. Based on World War I history, Kraus’s play features scenes that showcase the complicity of army generals, statesmen, journalists, and profiteers in war’s destruction. In doing so, the play addresses activities that still go on today, although the names of the offenders and the weaponry may have changed.

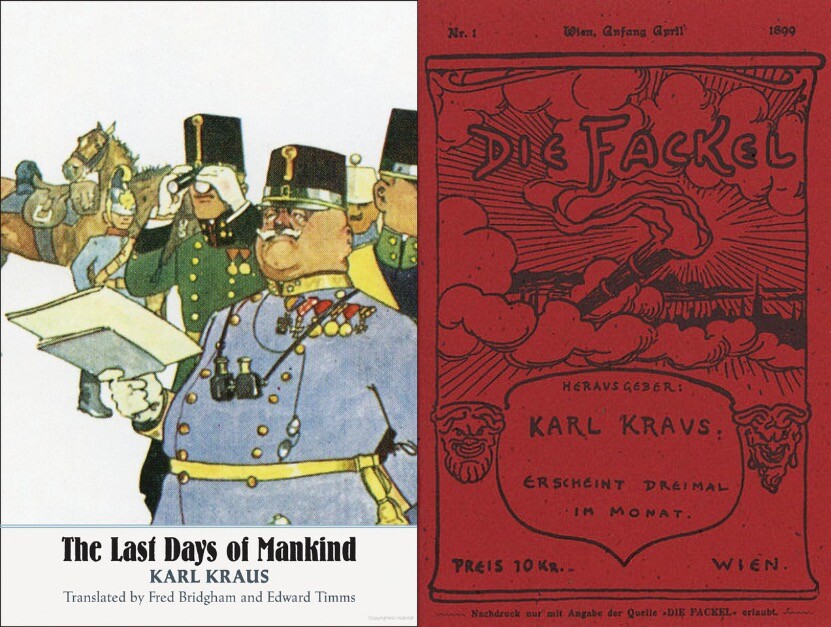

The one hundredth anniversary of a play predicting species’ extinction may not be the kind of centenary we all want to celebrate—and some might argue Kraus was wrong. The “last days” did not arrive in his time or decades after. But humankind remains an endangered species, and Kraus's depiction of a world at war remains both timely history and prophecy. The gargantuan anti-war play first published in German can be read in a fine English translation by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms. The end of the world (spoiler alert!) to which Kraus brings the planet is not entirely a loss, as it is preceded by biting satire and guest appearances by Armageddon's special friends.

Despite its great length and wealth of absurd, ironic humor, the play might benefit from a few new scenes, as international progress toward self-extinction has accelerated in recent decades because of nations competing to develop more lethal explosives and faster bomb delivery systems; CO2 and methane releases speeding us toward new disasters; and recent efforts to extinguish democracy and choice. A few scenes about war's contributions to climate catastrophe, white supremacy, patriarchy, and wealth inequality wouldn't hurt. But Kraus was ahead of his time—or at least anticipated our current era in his play—when he skewered aspects of war still neglected by Hollywood, most history books, and current war room occupants. He adeptly dramatized the abuse of language—the destruction of meaningful speech and its replacement by empty phrases. He opposed private and government-funded practices that initiate and sustain war through lies, propaganda, blind patriotism, and nationalism. (Ahead of Orwell, he saw how governments find truth inconvenient and dispensable, particularly in time of war.) The poison gas of World War I battles is preceded by lethal language, xenophobic harangues, arms contracts, and military orders that ultimately condemn large numbers of people to death and sustain or worsen existing inequalities.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Yes, Elliot Quick adapted the play for the Bard College production.

Another production to be noted is Robert Wilson's 2014 version, which included scenes from Brecht's "Schweik in the Second World War" as well as scenes by Kraus in a presentation titled "1914."

This play was done at Bard College a few years ago. Fred Kramer