Building Audience Into the Process

Recently we’ve started to see many a grant proposal and many a conference paper, and heard many a panel struggling with “audience engagement.” It’s the convening topic for the 2012 National Performance Network Conference, and a research topic for APAP’s Leadership Development group. It’s the next “new answer” to the questions that have been flummoxing the regions for the last ten years—how to attract audience under the age of sixty, and how to grow patron populations. Smaller independent companies have best captured the “under-sixty” audience, and because of that, some of the larger regional theaters have been supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (or have led themselves) to seek out these companies, commission works from them, and perhaps partner with them in order to attract new audience. These efforts and questions are laudable and necessary to making performance in the twenty-first century. Rude Mechs’ success in engaging our community and attracting new audience is entrenched in our programming, our aesthetic, and our longstanding partnership with our audience in the creation of our work—work that has become increasingly interactive over the years.

Rude Mechs’ demographic is 52% under the age of forty-five, 38% of that group ranges between eighteen and thirty-five. We create original work that springs from and speaks to our community. We have kept and grown our audience base because precisely how we engage with our audience has been a paramount part of our aesthetic since our inception. We think it’s the ongoing evolution of this engagement that is actually the important part. If trying out new ideas to reach a new demographic isn’t intrinsic to your artistic interests, and/or your institution’s programming, then it probably isn’t really going to “reach” anyone at all.

It has never been part of our mission to explore a singular form, or a particular set of performance ideas, or any through-line to our content. Our plays are wildly different from each other in terms of content, style, and form. Culturally, we have always seemed to be most attracted to the thing we’ve never done before. What our plays have in common is the collective aesthetic that resulted from our individual tastes and interests colliding play after play, year after year. And an ongoing and large part of that aesthetic is our deep concern for our relationship with the audience, and our audience’s relationship to the work.

However, as we began touring our work (Lipstick Traces, Cherrywood, How Late it Was How Late, Get Your War On), we began to notice a slight disconnect from our home-base, from the audiences that had been with us for ten years, at every show, sharing their opinions and desires at every talkback. Our physical distance from these people resulted in a spiritual and emotional distance as well. So we doubled down on our interaction with our audience by giving them a voice in our process as we create new works.

What our plays have in common is the collective aesthetic that resulted from our individual tastes and interests colliding play after play, year after year.

In 2006, we were awarded the Creative Capital grant for The Method Gun—a transformative moment for our artistic directors. This grant gave us permission to slow down, and the funds to pay artists for the development phase of the new play process—the most under-funded phase of collaborative work. And so, we gave ourselves permission to take longer than ten weeks to make and mount the play. And we also gave ourselves permission to put drafts up on their feet for our audience, making them members of our rehearsal project, including their “loves” and “hates” and feedback from draft to draft.

We began our work on The Method Gun in Summer 2007 at The Orchard Project. We flew out fourteen company members, and created scads of material. And we held weekly “lab nights” that Fall giving company members an opportunity to lead the group down any path they desired—around the central themes of the piece.

We presented the best of that work—nonlinearly—in a December 2007 work-in-progress showing, with a lively talkback. After that workshop, we made some very strong and difficult choices and ended up replacing about 70% of that material, as we moved quickly toward the April 2008 draft, which was presented by The Long Center for the Performing Arts here in Austin. At the talkbacks for those showings, they were flabbergasted at the changes in the material from just five months prior. When we mounted a new draft in 2009 at The Off Center, we were again met with deep surprise (some thrilled, some not so thrilled) at how much the play had changed since 2008.

The work of really talking to our audience about what collaborative new play creation entails was paying off as their expectations, their desires, their notes were giving them agency in the creation process of our work. I want to be super clear that this idea of showing work to audiences before it’s finished is age old, but it’s not something we had ever had the time or money to do with any consistency. It is luxurious, and has since become a de facto part of our process, to show our panties and reveal how much gets thrown out, what stays, and why—and to actively solicit and pay honest attention to audience feedback.

Another aspect of The Method Gun dealt with audience participation inside the piece. Remember, culturally, we tend to veer down new paths, and audience participation was definitely something we hadn’t up to that point ever intentionally explored. [spoiler alert!] In every showing of The Method Gun we begin by asking the audience to share with us the name of the teacher that has had the greatest influence on their lives (for good or for ill). These names are collected in a bowl on stage. In the world of the play, we report to them that this is a ritual Stella Burden used to perform with her students, burning the names at the end of her teaching to honor and release the lessons learned. At the very end of the play, the names in the bowl on stage burst into flames and are then projected on the back wall of the theater, dedicating the show to the audience’s own gurus and teachers. There is usually a strong reaction as audience members see their guru’s name scroll by, see that other people in the house shared that teacher. This places the community at the center of our work.

While we were developing and showing The Method Gun, we were also developing and showing I’ve Never Been So Happy. They were basically getting worked on in rotation. And, we were presenting Dionysus in 69 as part of a new audience education initiative, our Contemporary Classics series. Audience participation had leapt to the front of our brains as we were working on these new pieces.

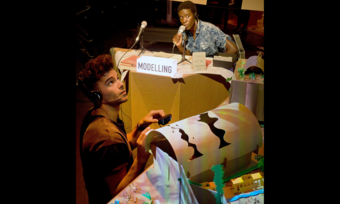

Humana Festival of New American Plays, 2010, Actors Theatre of Louisville. Photo by Alan Simons.

As we began work on I’ve Never Been So Happy in 2007, we were looking for ways to include work in the piece by artists in the company, and the community, and for ways to more actively engage our audience in the work (literally). And, Thomas Graves and I, as co-Directors, were looking for a “way in” without disturbing the already established collaboration between Kirk Lynn (writer) and Peter Stopschinski (composer), and without asking them to jam all of our opinions, thoughts, and desires into the narrative of the play. So the four of us conceived the (jokingly named) “transmedia performance party” to address all three desires. The transmedia performance party was built to house all of the fantastic artwork that we often have to leave behind when we are creating a new piece—our “darlings.”

The first version of this took place at the December 2008 workshop, and was the first thing the audience experienced. When they stepped inside the theater, they were given a map of installations—all of which were participatory: a western-wear store where they could check out clothing to wear for the evening, a margarita shop, a tent they could crawl into to watch video and listen to the sounds of Big Bend, a compilation video of interviews of the previous night’s audience about how their parents fucked them up, a room where they could give that interview, a visual art installation entitled “The Western Wing of the Gay Wax Museum,” a stuffed mountain lion and a real rancher both of whom you could ask any question you wanted, and a rube-goldberg-ish performance series that is almost impossible to describe here, but which gave them opportunities to interact with and inspire each other as they caused each other to play piano, paint, dance, and operate a remote control horse rider. They never really noticed the stage, and as the show began, they simply turned around to see the stage light up and watched the workshop production of five scenes from the show. The audience feedback was very exciting and centered on how their pre-show experience informed the work as they watched it, and how much they enjoyed feeling very much a part of the performance night.

The audience feedback was very exciting and centered on how their pre-show experience informed the work as they watched it, and how much they enjoyed feeling very much a part of the performance night.

For the September 2009 workshop production, we decided to move the operation outdoors and do it after the production—just to see how that might affect audience experience and whether it would still inform the actual piece. The Off Center is blessed with an enormous front yard so the installation was expansive and could include contributions from our favorite visual and performance artists in town, as well as company members. I believe there were at least fifteen installations, run by the cast members, including a phone bank where you could prank call a yankee, a pickup truck with a man inside that would let you touch a real gun, food deep-fried in the shape of famous Texans, a stage to sing western karaoke and practice two-stepping, Kirk’s dad set up his barber chair so you could get a hair cut, among others. We learned the curatorial impact of the installation was the same whether it occurred before or after the showing.The opportunity to interact with the cast in this way after seeing their work was especially appreciated. The carnival was as much a part of the show as the narrative. I don’t know that anyone could separate the two.

This format begun in 2007 of sharing our works-in-progress, and finding ways to engage our audience in the process and, eventually, in the work itself has found its way into our latest piece, Now Now Oh Now, which saw its first full-length draft in May 2012.

Inspired by evolutionary biology, the Brontës, and Live Action Role Play communities, Now Now Oh Now immerses the participants in an interactive puzzle reflecting on the challenges of navigating a world driven by competition, pleasure and random events. This show, more than any other to date, embodies our desire to create a more tangible, social, active, and personal experience for the audience. The evening is limited to an audience of thirty, that together solve a locked-room puzzle, which leads them to a lecture-demonstration on evolutionary biology, and once they solve their way out of that room, they are led to what might be described as a Brontëan flavored game of Dungeons and Dragons.

But the point here is not that all shows have to be participatory to engage audiences. The point is our audiences, many of whom we’ve known since our inception in 1996, need to know their opinions matter, and that we expect and appreciate their active involvement in the creative part of the process. They need to hear what each other are saying, and to know that what they say delivers vital information to Rude Mechs. They know their interest, their ideas, their passion and their participation—all of those things together—influence our work, inspire our programming, and keep us honest.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Timely and focused. Thank you.

I am very appreciative of this article, Lana. Folks who haven't seen the Rude Mechs in performance, or have maybe seen the company once on tour, not only don't know the sheer breadth of form, content and process that you explore, but also the audacious imagination with which you all approach this buzzy word 'participation' (cousin of the buzzier word engagement). Its so important that you, and other ensembles, chronicle and share what you are up to...your words act as prompts, invitations even, for all of us to keep pushing into new areas of working with our audiences/collaborators before, during and after production...can't wait to see something in Austin, I hope soon!

Hi Michael - Thank you, that means a lot. You should please drop everything and come hang out and boss us around in April when are working on Stop Hitting Yourself. Do it!

i am in rehearsal then, but now that you have invited me, i am gonna find another time to visit!