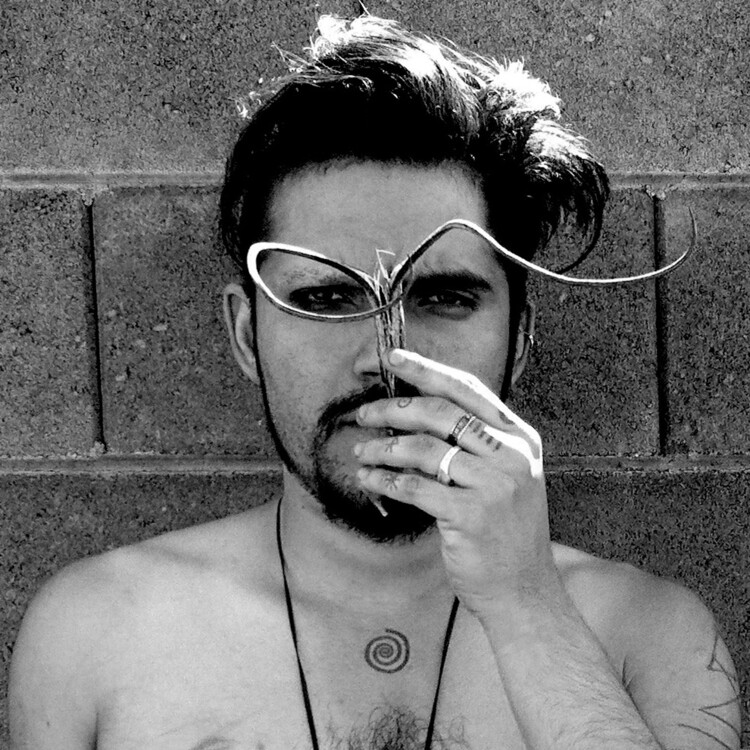

Anchuli Felicia King, a Thai-Australian cis, bisexual woman, is a multidisciplinary artist, but functionally considers herself a writer, mostly for theatre, but also for TV and film. These days, she is exploring the weird and wonderful world of doing online writers’ rooms over different time zones. Adam Cooper-Terán hails from the Southwestern United States in so-called Tucson, Arizona, the unceded lands of the Tohono O’odham. They identify as a Latinx-Yaqui-Jew, with heritage going into Mexico and Eastern Europe.

Anchuli Felicia King: You’re a designer, photographer, and video artist for theatre companies, performance groups, and musicians. Prior to the pandemic, how did the object of the internet function in your work, and how did it function internally in your stories?

Adam Cooper-Terán: In my work, the internet has always been a space to sample the alchemy of tags and memes. I didn’t really know what the implications of using the language of the internet as an occult practice were until maybe 2007 or 2008, when I began using Google Images as a way to derive media from a textual “crystal ball,” so to speak. The way a magician “spellcasts” to get their intended results, I was inputting words or phrases into the search engine and those results would be combined into these visual landscapes or multimedia collages. It was more about the coded language of the image or the metadata behind it to create an intended message or impression for viewers.

A lot of my digital work was heavily based on sampling and collaging hundreds of layers into spaces that I would consider landscapes. They were these large-scale printed representations of different themes or tags that related to a particular concept, such as an invocation or evocation of a particular Spirit or entity, or a death ritual. Before I used Google, it was AltaVista, and before AltaVista, it was Netscape. Linguistic inputs became the foundation of a very cut-up process, but also the building of something new. And video was a big part of that, too.

There was a period of time in 2009 or 2008 when a lot of websites hosted videos of the first memes—sites like eBaum’s World or even Google Video. Those became spaces to sample from, but because there was no software or plugins to download the movie file, I had to create the video sample by placing a camera in front of the monitor and recording the screen. Everything was being recorded to tape and then retransferred to the computer, so there was more of this deconstructing or dismantling of the literal data I was experiencing from these search engines or from a web browser.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here