Dispatch from Tehran—33rd Annual Fadjr International Theater Festival, Part 1

The 33rd Fadjr International Theater Festival, Iran’s most visible dramatic showcase, opened in Tehran on a cold and cloudy Wednesday. The festival program is made up of staged plays, radio plays, street performances, workshops, and lecture-demonstrations. Eighty plays from Iran and eleven from Europe and the Middle East, including three collaborations between Iranian and European artists, were staged at ten venues over twelve days, January 21-February 1, 2015. Once again, there was no representation from the United States.

The Fadjr Festival is the post-revolution incarnation of the annual International Art Festival that used to take place in Shiraz that once boasted of hosting such luminaries as Peter Brook, Ravi Shankar, and Maurice Béjart.

US-Iran relations have been frigid since the 1979 revolution that toppled US-ally Mohamad Reza Shah Pahlavi and eventually replaced the monarchy with an Islamic Republic. Iranian students taking Americans hostage in the Tehran US Embassy did not help the situation either. That Embassy has now been turned into a museum and while a giant mural on a nearby street still reminds passersby of the once popular “Death to America” slogan, not much else remains of those zealous days. Iran has certainly changed from its absolute pro-west stance of the 1960s and ’70s. Revolutionary zeal, however, has given way to more practical priorities such as balancing the budget.

The Fadjr Festival is the post-revolution incarnation of the annual International Art Festival that used to take place in Shiraz that once boasted of hosting such luminaries as Peter Brook, Ravi Shankar, and Maurice Béjart. The Festival website explains:

Fadjr International Theater Festival is the most important display of theatre annual activities in Iran, is held by the Dramatic Arts Centre of the Islamic Culture and Guidance Ministry on the occasion of the anniversary of Islamic Revolution’s victory.

The Festival reached its artistic peak during the presidency of Mohamad Khatami (1997-2005) who was Minister of Culture prior to taking the helm as president; his administration was eager to rebuild Iran’s stature as a cultural leader. Khatami supported the arts and funded cultural programs generously. But the eight years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency (2005-2013) took a toll on the arts in Iran. Budget cuts, mismanagement, and political pressure forced many theatre artists to leave the country or explore alternative modes of producing work. Since taking power in 2014, President Rohani has promised to support the arts, but his administration’s top priority is the economy.

Budget cuts, mismanagement, and political pressure forced many theatre artists to leave the country or explore alternative modes of producing work. Since taking power in 2014, President Rohani has promised to support the arts, but his administration’s top priority is the economy.

And so the 2015 Festival opened in a climate of frustration. Many question its very purpose given the lack of adequate funding, leadership, and Iran’s international isolation. Despite the criticism, and some artists’ refusal to include their work in the Festival, many are eager and honored to be represented. These artists welcome the chance to interact with the international artists that are present. (Some international artists, including Americans, did not accept the invitation to attend the Festival in support of Iranian artists’ call to boycott Iran’s censorship laws as well as continued oppression of artists and intellectuals particularly in the aftermath of the 2009 “Green Movement.”)

I was born and raised in Iran and still have family there that I visit as often as possible. But since taking a six-month sabbatical in Iran in 2010, my professional relationship with theatre artists there has deepened. I have developed great respect for artists who continue to create under serious pressure and control.*

This year I was in Iran for much of January and fortunate to catch the first few days of the Fadjr Festival. The lineup of plays was announced only two weeks before the opening of the festival, which did not allow much time for planning. But I managed to catch a few performances nonetheless. Two stood out: Goftegooye Fararian (Fugitive Conversations) written by Mohammad Zare’i and directed by Milad Shajareh; and Parvaz bar faraz-e Shahr (Flight above the City) from Armenia written by Anush Aslibekian and directed by Narine Gregorian.[caption]

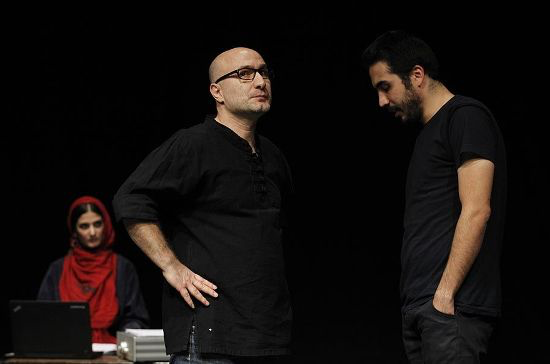

Photo by Elnaz Dadmehr from teater.ir. [/caption]Goftegooye Fararian (Fugitive Conversations) was set in a bare rehearsal room where a writer/director is rehearsing his new play with his lead actor. The stage manager quietly supports and observes. The play starts with an argument about using clear language, and the importance of discussing issues. The lead actor wants to better understand the playwright/director’s intentions, but the director is adamant that there is nothing to discuss. We understand there is more at stake than truthful representation of a scene. The action is confined to a square taped on the floor, a prison of sorts. The play within the play, set in Nazi Germany, depicts the conversation between two fugitives: an officer of the Third Reich and a Jewish physicist who depend on each other for safety, yet are untrusting of one another’s intentions. This relationship parallels that of the director and his lead actor, at times implying infidelity and betrayal.[caption]

Photo by Elnaz Dadmehr from teater.ir. [/caption]As the play moves forward, the dynamics shift and the power of language—its expression as well as the information it can withhold—in establishing and maintaining dictatorial power is amplified. Reza Behboodi delivers a gripping performance as the playwright/director who accuses his lead actor of having an affair with a woman we presume to be the director’s lover. Through carefully escalating arguments, Behboodi portrays a frustrated artist simultaneously excavating and distrusting of language, a man on the verge of explosion who uses language as a tool for oppression, a director who is as dictatorial in the rehearsal room as the dictator he depicts in his play. When the Behboodi character begins spewing a passionate speech in German (a passage from Mein Kampf?) in unmistakable Hitler-esque style, the lead actor stops acting, refuses to go on, and leaves. The director then commands the stage manager to leave and crumbles on stage alone. He has no one left to oppress. The bare stage, the casual clothing of the actors, and the intimate space make the separation between actor and audience disappear. I felt the audience become visibly uncomfortable when the director launched into his dictatorial speech. If this was an intentional directorial choice, it was certainly successful.[caption]

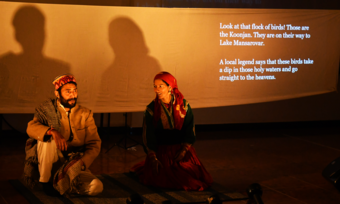

Photo by Elnaz Dadmehr from teater.ir. [/caption]Parvaz bar faraz-e Shahr (Flight above the City) opens with a tableau of a girl within a child-like drawing. The play begins as the lines in the drawing (colorful yarn) are pulled away, freeing the girl from within the drawing. The storybook environment of the play is enhanced with a voice over—a comforting male voice puts the little girl to bed. Next the comforting male voice offers tea. The little girl is now a young woman. She mimes the tea drinking ceremony—every absent material and item is intricately represented through gesture and sound. We hear the clicking of her spoon to the china cup, and the swirling of the liquid in the cup as she mixes in her invisible sugar.[caption]

Photo by Adis Shant from teater.ir. [/caption]The young woman is drawn to intense sensory experiences. For example, she cherishes every taste and sensation of biting into a whole lemon. A doctor’s voice laughs at her childish delight. We suddenly understand why all is invisible—the young woman is blind and we are seeing and hearing the world through her eyes and ears. The young woman makes inquiries to the doctor, and his comforting male voice patiently responds to her endless curiosity about the world outside.[caption]

Photo by Adis Shant from teater.ir. [/caption]Next, the empty space shifts and the young woman disappears. The man/doctor arrives and sets up a little apartment with a large window overlooking the city replete with blue sky and birds. A departure from the lyrical world we previously experienced, the semi-realistic design of the apartment gives the impression that we have left the dream/story world. When the young woman returns, we realize she can see. The man/doctor continues to treat her like a child/patient; she resents this, but he does not know another way. The young woman leaves.[caption]

Photo by Adis Shant from teater.ir. [/caption]The man is left alone in an apartment that is designed to be reflective of the young woman’s every need; an apartment that was home to their rituals. The man questions how he shall go on. Then we hear the comforting voice of the young woman: “Shall I read you a story?” The man pours himself a cup of tea, mixes sugar in his cup, and takes a bite of a large juicy lemon. This romantic and lyrical gem was a welcome departure from the usual harsh and cynical themes that tend to dominate Iranian theatre.

Many of the other plays staged at the festival (such as Khaneh-Vadeh, Goftegooye Fararian and Biroon Poshte Dar) dealt with oppression and control. In fact, love may be the most threatening topic on the stages of the Islamic Republic. For one thing, men and women are prohibited from physically touching on stage, which makes staging a love-scene rather challenging. The expression of love, unless for country or God, is frowned upon by Irshad, the government body charged with maintaining Islamic values in the arts. Irshad is the body that must approve texts and productions of all plays before they are published or begin rehearsal.

In fact, love may be the most threatening topic on the stages of the Islamic Republic. For one thing, men and women are prohibited from physically touching on stage, which makes staging a love-scene rather challenging.

The front courtyard of Teatre Shahr (celebrating its 42nd birthday) is decorated with Fadjr Festival signs and a retrospective photo exhibit. It pulsates with masses of theatre lovers who fill every performance space. Experiencing theatre in Tehran, among mixed audience of varying age and piousness,** I am reminded just how integral theatre can be to a community’s daily life. Somehow theatre seems to matter more to people outside of the United States, where there are less abundant entertainment options. In any case, I miss this feeling of theatre that matters, of performances that are discussed for days after. I’m left in awe of the artists who, despite the challenges, passionately, and often with minimal support, continue to tell their stories.

***

* I was so incredibly impressed with the many plays I saw in 2010 that I felt compelled to share my experience with my American colleagues, in articles published in The Drama Review (spring 2012) and American Theatre magazine (2010).

** In Tehran, piousness can be evaluated based on how strictly one follows Islamic codes of dress.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here