Cold rain drummed upon the streets of India’s Dharamshala region and snow sheeted the higher peaks of the Dhauladhar mountains. I was glad to be dry and indoors in an intimate performance space, but gladder still on that cold day earlier this year, in March, to hear birdsong and folk stories in the sweet Gaddi language, reminiscing a time long gone. I later realized what had actually warmed me in that room was the strength of freshly brewed solidarities—a sense of being a collective and a community—enabled by the creative endeavor of theatre.

Foundations for a Cross-Cultural Community Theatre in Dharamshala

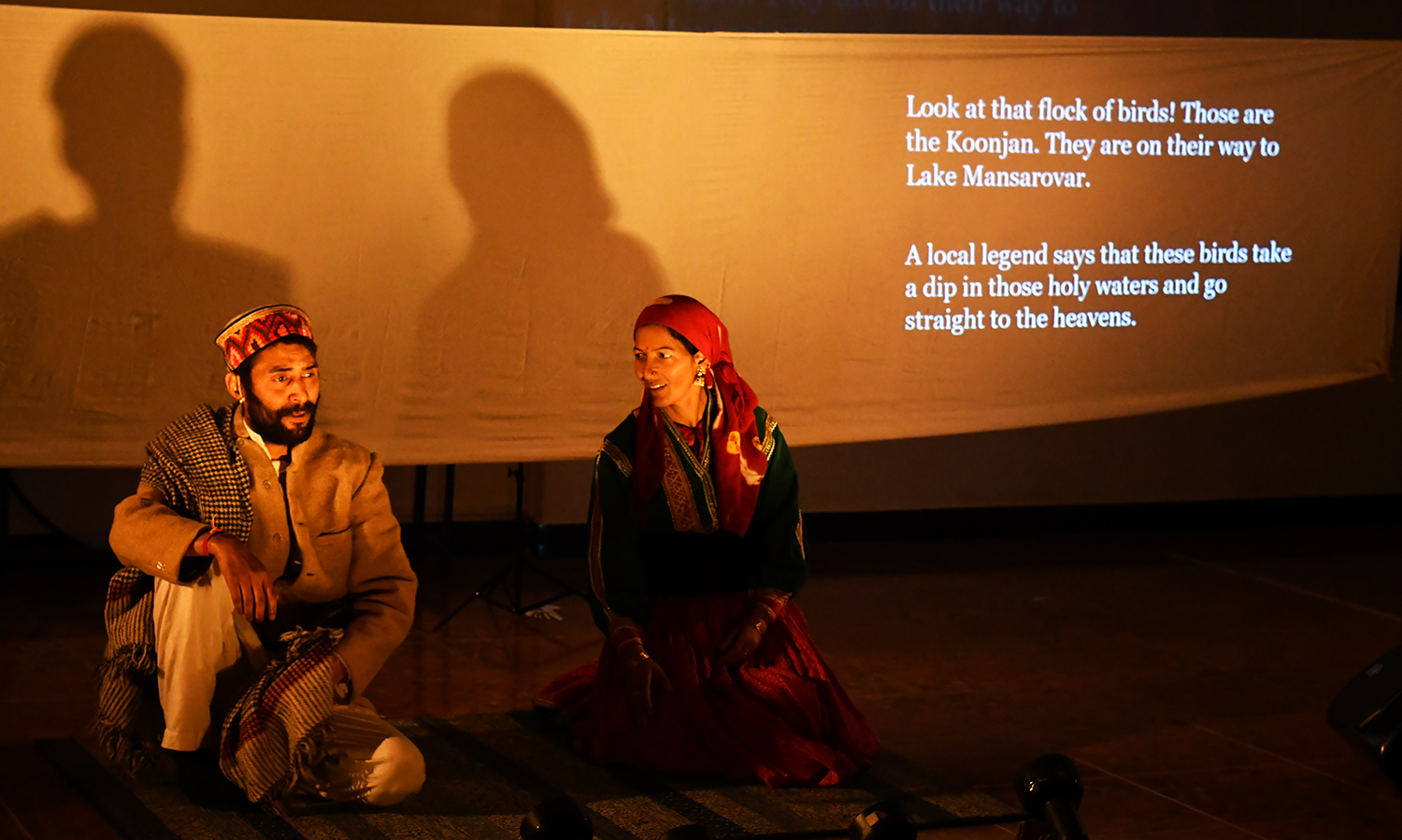

Birds—the first contemporary theatre production in Gaddi. Photo by Poorva Gupta.

The performance I was there to see, Birds, had been produced by d.r.i.f.t.—the Dharamshala Residential and International Festival for Theatre. The small team was comprised mostly of local artists who were fairly new to performing on stage, with day jobs and roles as diverse as farmers, students, mountain guides, models, photographers, homemakers, activists, and music composers. Belonging to different linguistic and ethnic communities living in Dharamshala, they had found the opportunity via d.r.i.f.t. to come together beyond the functional and transactional. In Birds, they braided together folktales and fresh compositions of folk songs about the birds of Kangra, the region that Dharamshala is in. Written with elegance and subtlety, the performance extended solidarities beyond the concerns of their daily lives relevant to this valley. While it talked about the comings and goings of the birds with each season, it simultaneously addressed questions of migration and citizenship that had gripped India in the last few months.

d.r.i.f.t. is a theatre project based in Dharamshala, a hillcity in India nestled in the shadows of the lower Himalayas. Initiated by theatremaker Niranjani Iyer in 2016, the project is fuelled and directed by community efforts and needs. Following previous projects that created interactions in public spaces, Iyer, an alumni of Paris’s École internationale de théâtre Jacques Lecoq and guest faculty at New Delhi’s National School of Drama, had further questions on her mind: Is it possible to build theatre audiences and practitioners from scratch in a semi-rural area?

“Despite being cosmopolitan in terms of people, conversations, and cuisines,” shares Iyer, “all these groups were functioning more or less exclusively.”

The Demographics and History of the Region

Dharamashala has a unique demography and history. People of the Gaddi tribe, descendants of previously nomadic tribes, live all along the flanks of the mountains. Then there is the Tibetan community in exile, which has called Upper Dharamshala home since 1959. The Tibetan Buddhist leader, the Dalai Lama, and the Tibetan government-in-exile are based here, as are scores of Buddhist monks, practitioners, and long- and short-term tourists. Finally, in recent years, the city has also seen an influx of entrepreneurs, freelancers, and daily wage laborers from other parts of India.

Iyer mentions that, when speaking of Dharamshala, the focused gaze on the Tibetan community has done the local inhabitants a great disservice and at times created animosity between communities. I can confirm this blinkered perception myself: even though I have visited Dharamshala many times, I never consciously paid attention to Gaddi language or culture.

“Despite being cosmopolitan in terms of people, conversations, and cuisines,” shares Iyer, “all these groups were functioning more or less exclusively—foreigners mostly only interacted with Tibetans, Tibetans didn’t interact with local Indians much, nor did the foreign travellers.” As a social phenomenon, Iyer found this interesting and disturbing. In response, she wanted to present art that disrupts, art that brings together people who don’t usually interact with each other.

d.r.i.f.t. up in the hills. Photo by Pallavi, d.r.i.f.t.

The Collaborations and Their Impact

Engaging deeply with the locals then became a declared goal, and the team—who work entirely on a voluntary basis—organizes events related to theatre towards this end throughout the year. There’s a mix of performances, workshops, talks, readings in neighborhood cafes, and outreach programs with schools in the region. Striving to remain accessible and affordable to everyone, tickets are priced between Rs 50 and Rs 200 (around $0.67 USD to $2.68 USD) on a pay-as-you-wish basis.

Interactions and collaborations enabled by the project have led to greater exchange and empathy among the various communities. For instance, the yearlong program with schools led to the first ever collaboration between the Lower Tibetan Children’s Village school and an Indian school, Gamru Village. When children of underprivileged migrant laborers and second- or third-generation Tibetan refugee children worked together on the production Ek Anek, they translated lessons of unity, diversity, and intersectionality through theatre. The performance was a theatrical adaptation of the 1974 Indian educational film for children Ek, Anek aur Ekta (One, Many, and Unity) and was a reminder of the pluralism that was envisioned in the making of this nation. The title song calls out: “Phool hain anek kintu mala phir ek hai,” meaning: “there are many flowers, and yet they make one garland.” As Iyer says, “This diversity has been our focus right from the beginning. This is why we wanted a play in Gaddi and Tibetan so that we hear other languages, and so that we are not doing theatre in Hindi or English just because that’s easy for the audience.”

This kind of non-hierarchical approach creates the foundations for inclusivity and a lightness of spirit that spills across the festival and infects festivalgoers, too.

The idea of a diverse collective absorbed the festival this year right from its kickoff, with a solemn reading of the preamble of the Indian constitution. This was a subtle performative protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act—recognized for being anti-Muslim and altering fundamental principles of secularism enshrined in the constitution—recently proposed by the Hindu-majoritarian Indian government. While there had been widespread protests and occupation of various sites by protestors across the country, the performers here registered their stand on the issue through an evocative reminder and celebration of the country’s diversity.

The 2020 edition of d.r.i.f.t. also produced and presented a multilingual adaptation of Eve Ensler’s The Vagina Monologues with local amateur actors performing the narratives of women’s sexual experiences in English, Hindi, Gaddi, and Tibetan. This was not just the first time ever this play was performed in Gaddi and Tibetan, it was also the first instance of contemporary theatre performed in these four languages as an ensemble. The actors shared some of the many revelations they encountered while translating the play into their respective mother tongues, one being that there aren’t commonly known playful words for vagina in any of these languages—or in other Indian languages for that matter. The performance was bold for the patriarchal context of India, particularly in semi-rural parts of Dharamshala, where the team live and work among the communities they perform for.

Vandana Kapoor, who made her stage debut this year with not one but two plays, Birds and Vagina Monologues, emphasized a more personal aspect of the impact of performing in Gaddi. “Researching and recalling Gaddi songs and working on Gaddi translations has been a special journey of rediscovering my relationship to my mother tongue,” she said. “Performing in the first-ever Gaddi language play has infused me with pride and confidence.” Kapoor also shared how the entire team was encouraging and supporting her in this new experience, including by taking turns to care for her five-year-old child. The sharing of responsibilities is carried on during the festival too: performers, organizers, and volunteers all live and cook together, and everyone shares duties for aspects such as backstage set up, front desk management, and ushering. This kind of non-hierarchical approach creates the foundations for inclusivity and a lightness of spirit that spills across the festival and infects festivalgoers, too.

With many arts practitioners moving to Dharamshala to escape the polluted air and fast-paced life in the metropolis, they find themselves arriving at a town that is rife with possibilities for interdisciplinary and cross-cultural collaborations.

Stoking the Fire for Theatre in Dharamshala

Theatre is a relatively new mode of engagement for people in Dharamshala. Gaddi culture has folk dances, music, and oral storytelling practices; traditional Tibetan performances are practiced at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts. d.r.i.f.t.’s attempt at generating contemporary theatre in Dharamshala has also expanded into a pedagogical and exchange process. In 2017, for example, the Sangeet Natak Akademi Awardee Purva Naresh conducted a writing workshop that enabled ten new plays to be written, six of which were later staged. d.r.i.f.t. Reads—one of the programs that continues through the year—attempts to familiarize people with reading aloud and performing in public. Tenzin Kunkey, a massage therapist who started her journey with d.r.i.f.t. Reads in 2016, was one of the performers in The Vagina Monologues this year. She says: “My diction, sense of comfort, and naturalness evolved with the various workshops, where I was exposed to different styles and people. It has been a developmental leap for me from d.r.i.f.t. Reads to performing on stage.”

The festival has also invited practitioners from India and around the world to perform and lead workshops on various facets of theatre and movement. Workshops have covered physical theatre, voice, and breath in performance, puppet theatre, theatre of materials, as well as foundational and allied aspects of performance-making such as light design, performance production, and script writing. A cosmopolitan Dharamshala has also pushed d.r.i.f.t. to include physical theatre performances such as Nidravathwam (by Adishakti Theatre, Pondicherry) and Black and White (Akhokha Theatre, Manipur) in 2019. The festival also encourages local contemporary dance-theatre productions: this year, Timelines was performed by two Tibetan youth from Dharamshala who were mentored by choreographer Surjit Nongmeikapam from Manipur.

Working with existing local performance practices and material, and adapting them to experimental modes of presentation, is also important for d.r.i.f.t. Birds narrated local folk tales using shadow theatre and included traditional Gaddi folk songs in fresh musical arrangement by Anant Dayal, a storyteller-musician. “The quality of attention the audience brings is very special, says Dayal. “Even if there hasn’t been much theatre before, the audience is not innocent or callow. Dayal mentions, too, that the performances get meaningful responses, as attendees really engage with the shows and have pertinent questions and observations afterwards. With many arts practitioners moving to Dharamshala to escape the polluted air and fast-paced life in the metropolis, they find themselves arriving at a town that is rife with possibilities for interdisciplinary and cross-cultural collaborations. What Iyer initiated with d.r.i.f.t., and what is now being borne and shaped by the local performers, is a reminder of the power of the collective, of the delightful shifts that are possible when creativity and community are brought together.

Vagina Monologues. Photo by Pallavi, d.r.i.f.t.

As I was leaving the hills after the festival, my mind wandered to Tenzin Tsundue’s poem “When It Rains in Dharamshala”:

I sit on my island-nation bed

and watch my country in flood,

notes on freedom,

memoirs of my prison days,

letters from college friends,

crumbs of bread

and Maggi noodles

rise sprightly to the surface

like a sudden recovery

of a forgotten memory.

The clouds had thankfully cleared but Tsundue’s atmospheric evocation of Dharamshala stayed with me. His words reminded me that although this a small town, the people here have lived lives and have stories that ought to be heard. I hoped that on other rainy days, a thousand other tales in the many tongues of these mountains—Gaddi, Pahari, Tibetan, Hindi, and the languages of other migrants who call this home—would rise sprightly to the surface, perhaps through a flood of theatre.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here