Star Finch: I wanted to talk with fellow playwrights about Broadway and specifically Black playwrights on Broadway. I’ll start by asking

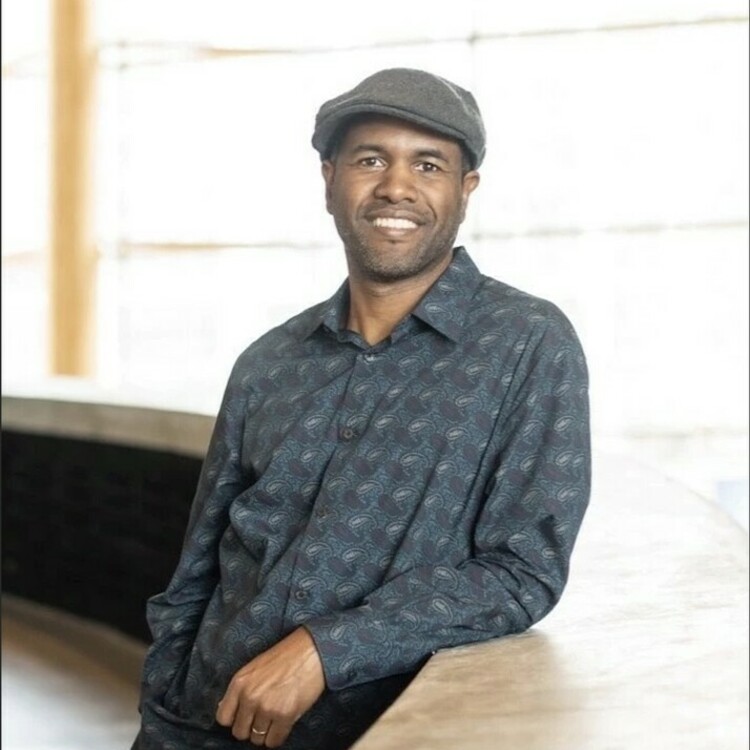

Psalmayene 24: Broadway was actually one of my first theatrical experiences. Growing up in Brooklyn, I went on a couple of field trips to Broadway in elementary school and junior high school, so that was my introduction in a lot of ways to professional theatre. Those formative experiences impressed my mind with a certain type of approach to theatre—a certain type of style, even. Even though my own personal theatrical style has veered away from those early shows that I saw, Broadway does hold a special place in my heart because it’s connected to my childhood. Now as I’ve matured and developed as an artist, I understand Broadway as something different. My understanding of it is more complicated. Now it represents the pinnacle of crossing over commercially in theatre. It also represents integration in a way that is not as simple or idealistic as one might think. While Broadway for me is not the be-all, end-all, I’d be disingenuous if I said it isn’t part of a personal long-term vision.

J. Nicole Brooks: I love this question. I hate this question. I was jumping through all the hoops and carrying around something to break every glass ceiling. I thought I was doing all the things that said, “If you follow this path, it will lead you to Broadway.”

And where I am now is, Oh my God, I’m so glad that Broadway is not my goal. I think the years that I worked and lived in Los Angeles helped me to realize that Los Angeles is not a mecca. It’s just a town. New York is a town. Neither determine success. I have so much deep respect and admiration for the Black artists that are currently working on Broadway. It is so difficult. But for me, I’m glad to be at a point where it is not my end-all, be-all. But if it happens, it happens.

Star: Growing up, I would visit New York because I have family there. And I think in my mind as a kid, Broadway was musicals for tourists. And then when I got a little older, I had a queer uncle who would always show me old Bettie Davis movies, movies from the forties and fifties. And whenever there was a reference to Broadway in those old films, it just seemed like a really cool club—like the hip place for talented people to be. I don’t know if Broadway wrestles with that question of whether it’s about entertainment for tourists or if it’s about Broadway being the pinnacle of the art form.

But I do want to get back to all the Black artists who are on Broadway and are doing their thing. This question really came up for me in December when—I’m sure y’all heard about it—the whole campaign for Ain’t No Mo’ by Jordan E. Cooper closing. A lot of Black celebrities came together to buy tickets and it had all this critical success and it just felt like, how is this thing closing? You know what I mean? People are loving it, but people weren’t filling the seats. And I read about how Jordan E. Cooper is the youngest Black American playwright on Broadway with Ain’t No Mo. And then at that same time, Adrienne Kennedy was making her Broadway debut with Ohio State Murders at the age of ninety-one.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here