Encountering Eastern Europe

In September and October 2016 with the support of the Trust for Mutual Understanding, HowlRound Cultural Strategist Vijay Mathew and I went on a trip to explore, deepen, and build new HowlRound partnerships with theatremakers and organizations in Eastern Europe.

While I grew up during the fall of the Soviet Union, it’s important to acknowledge that Western anti-communist propaganda and the lingering effects of the Cold War kept me distanced from any realistic notion of life and culture in Eastern Europe.

This trip was an opportunity to see the region for the first time, firsthand, and to engage its people and history through a lens that only art and culture can provide. All in all, it was twenty-one days on the road, four cities, four currencies, three festivals, a conference, lectures, countless new faces, meetings over coffee, over food, over drinks, and to cap it all off, twenty-three shows.

Stop 1: The International Festival Divadelná Nitra in Nitra, Slovakia

We met a Festival volunteer, a student majoring in translation, originally from Ukraine and eager to practice her English, and a grumpy Slovakian bus driver straight from central casting in the parking lot of the Flughafen Wien / Vienna airport and drove East. The countryside was beautiful—farmland and massive wind turbines for miles, the light seemed different here. Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia is only an hour from Vienna, but it might as well be half way around the world. Later in the trip I learned that these two capitals used to be much more economically and culturally linked—before the communist era, a short tram ride used to connect the two capitals.

It was twenty-one days on the road, four cities, four currencies, three festivals, a conference, lectures, countless new faces, meetings over coffee, over food, over drinks, and to cap it all off, twenty-three shows.

Though it entered the European Union in 2009, Slovakia has not fully recovered from its time behind the Iron Curtain. When Czechoslovakia split in 1993, Slovakia and the Czech Republic were born. Slovakia was the clear loser in the split. Nitra, a college town nestled at the foot of the Zobor mountain in the central part of the country, is the fourth largest city in Slovakia, with a population of 80,000. As we drove into town, “Careless Whisper” was playing in the background like it was 1984 all over again, and our guide made sure we noted the castle sitting above the city, a hometown point of pride.

It felt like we were entering a time warp. The town seemed fifty years behind its neighbor to the West. Brutalist architecture and pre-Communist leftovers lined the streets. The theatres were full of rotundas and hard lines and symmetry. There was a kind of kitsch we branded “Soviet Lux” that is inescapable—fake flowers, silk-ish napkins and slipcovers, gold accenting, blonde theatre ushers wearing matching red skirts and suit jackets who bear a distinct resemblance to Ivana Trump, and in the background, American pop music from the 80s and 90s. It seemed cool to wear T-shirts that say “Cali Bay Area,” or “Detroit Mich.” A sort of English was heard.

Everyone smoked, and it showed. A pack of cigarettes was about $1. Our hotel reeked of smoke, but they tried to cover it up with a sweet, strong deodorizer that smelled like peach. Later, I’ll recognize this smell again in Belgrade and Bucharest and it will almost turn my stomach.

I went for an early morning run in Mestský park. The pavement was uneven, and the monuments looked unkempt. A fountain sat, filled with green water, in disrepair. Old men walked tiny dogs. A man squatted to shit as I passed by. This was most definitely not Vienna.

There was an old broken clock across the street from the ultra-modern shopping mall that displayed local time as well as times in Moscow, Hanoi, and Havana. It took me a while to realize that what united those cities was communism.

International Festival Divadelná Nitra was celebrating its twenty-fifth year. It’s a regional festival, and had a strong reputation in earlier years, but general consensus is that the programming has suffered recently due to a decrease in government subsidy. The main program was half local and half regional. The theme for the festival (they all have themes) was “Ode to Joy?”

Europe is a big and proud ship… The ship sails today under the flag of democracy and peace, ethnic religious, racial and gender tolerance. It strives to keep the course of liberalism and solidarity, to pass on the legacy of cultural maturity and protect the environment… What are the genuine European values? Which of them have withstood globalization, commercialization or skepticism? And which of them has Europe buried under the layers of disappointment from the unprecedented commotions and catastrophes? —Darina Kárová, Festival Director

This festival, as did every other festival we attended, talked about being a home for the meeting of East and West, and featured multiple shows that dealt with immigration, war, and otherness. In the circular plaza outside of the main festival location, the Andrej Bagar Theatre, sat an art installation of large white letters surrounded by plants called “Message from the West.” It read “You Are The White Guys From Eastern Europe.”

We saw eight of the eleven shows that were part of this festival. Pillars of Blood by Iraq Bodies, directed by Anmar Taha featured an Iraqi dance theatre company who have been in exile in Sweden since one of their company members was shot and killed; a Slovakian double feature of playwright Ewald Palmetshofer’s absurdist pieces Hamlet is Dead directed by Svetozár Sprušanský (Slovakia) and Faust is Hungry directed by Braňo Holiček; The Hearing by Tomáš Vůjtek, directed by Ivan Krejčí, a much lauded show from the Czech Republic which was a fictional reconstruction of the war crimes hearing for Adolph Eichman, one of the architects of the Holocaust. This was my first foray into watching theatre with simultaneous headphone translation and it was a trip.

Next up was Kantor Downtown by Teatr Polski Bydgoszcz of Poland, created by Jolanta Janiczak, Joanna Krakowska, Magda Mosiewicz, Wiktor Rubin. The show explored how

the work of Tadeus Kantor impacted the avant-garde scene in New York City in the 1960s and 1970s, and its legacy today. Empty Hole by Michal Vajdička and company, directed by Michal Vajdička from Bratislava, Slovakia, was perhaps the best received show in the Nitra Festival, and it was entirely about the (depressing) reality of contemporary Slovak life. The cast was filled with well-known Slovak actors who do TV and film as well. It presented some facts about Slovakians, presumably from some kind of national survey, which painted a pretty bleak picture, such as: 90 percent of Slovaks believe the government is corrupt, 60 percent of Slovaks want to leave the country, 11 percent are on the brink of poverty, 33 percent of Slovak women are victims of violence, 11 percent of Slovaks are alcoholics, 11 percent of Slovaks are happy. People were rolling in the aisles. I was confused.

Opernball by Petra Fornayová of Bratislava was a contemporary dance theatre piece about the effects of mass media (and mass fan culture) looking at the immensely popular Viennese Opera Ball, a high society/debutante/cotillion type event that is now broadcast live on Austrian TV with sports-like commentary. French Compagnie Du Zieu, Fère-en-Tardenois’ Suddenly the Night by Olivier Saccomano directed by Nathalie Garraud featured a group of passengers quarantined at a French airport after a passenger on their plane who was using a fake passport dies. Is what he died of contagious? And was spreading this sickness part of a terrorist plan?

At this festival we were able to meet HowlRound contributor and Hungarian critic Tamás Jászay in person. One of the interesting perspectives he shared with us was that nearby Hungarian and Czech theatres are more financially backed than those in their more economically depressed neighbor, Slovakia, who gives a lower percentage of GDP to culture.

Photo by Jamie Gahlon.

Every morning there was two-plus hour discussion with creators of shows from that night or the previous night. We livestreamed the closing session (in English and Slovak). These events were open to the general public, but primarily attended by the participants in the V4@Theatre Critics Program, a program for emerging critics from the Visegrad (V4) Group countries, now in its second year. The program was created to train the next generation of critics, and also to try and solve the practical problem of loss of critical coverage of the festival. The twelve participants saw every show, wrote reflections about them, and had in-depth conversations with the program’s mentor, French critic and educator Patrice Pavis. On this trip we met many people who are cultural critics, a role that felt more important and legitimized in Europe than in the US.

The Dirty Dancing soundtrack played during the closing night party in basement bar of the Andrei Spesak theatre. Almost exclusively young people crowded into the space, sitting on stairs. One of the young critics remarked that this space would be sad tomorrow, once the festival was over. I asked why, and she responded that while this used to be a really vibrant theatre community, just recently a local official had fired the artistic director and theatre staff and installed a friend instead. The same thing had also recently happened at four theatres in the Czech Republic. When theatres are subsidized so heavily by the government, it seems they too are at the whims of those in elected office.

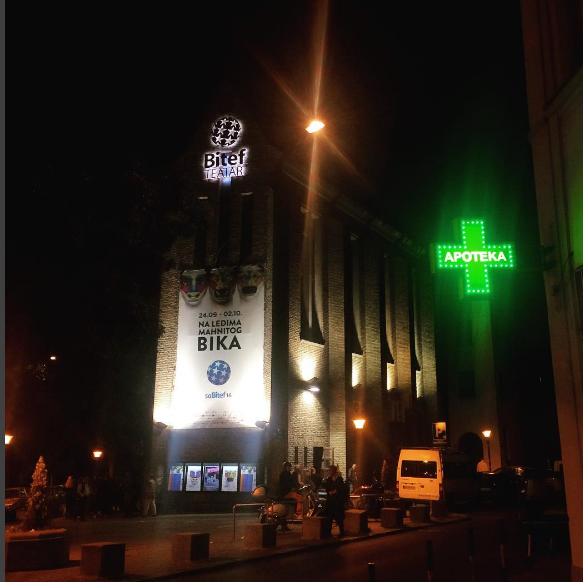

Stop 2: The Belgrade International Theatre Festival (BITEF), Belgrade, Serbia

Belgrade is a lively capital city of 1.3 million, situated on the Danube and Salva rivers, at the geopolitical and strategic crossroads of East and West—bordered by Hungary to the North, Romania and Bulgaria to the East, Kosovo (though it is currently disputed territory) and Albania to the South, and to the West, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzogovina, and Montenegro.

At once a bustling modern metropolis and an olio of different eras, political actors, design imperatives, best understood by the fact that through history it has been destroyed and rebuilt forty-four times. What you see in the city today is one part Darwinian survival, one-part total chance. We stayed in what was once known as the artsy, bohemian district, Savamala, but is now beginning to gentrify, in part due to the city’s rapid and so far partial transformation of the waterfront into a commercial and tourist destination. The city, bolstered by foreign investment, has razed homes to make way for new luxury hotels, boutiques, and food trucks. Driving to the hotel we were told that we may even see the tail end of protests over this redevelopment.

There was a dark edge to Belgrade; I wouldn’t want to walk alone at night. It didn’t help that half of the signs were in Cyrillic so there was no telling where I was most of the time. Graffiti, street art, and murals were everywhere. Many of the concrete buildings erected during the communist era following World War II were beginning to crack. There was a pretty pervasive sense of disrepair. Stray dogs and cats roamed the streets.

A part of Yugoslavia until its break up in 2006, Serbia is currently a candidate for European Union membership. During the Kosovo War in 1999, NATO bombed Belgrade. At this same time, former (and first) Serbian President Slobodan Milošević was charged by the International Criminal Court with war crimes in connection with recent wars in Bosnia, Croatia, and Kosovo. Looking over the Danube one night, I commented on the beautiful view—someone remarked that civilians laid down on the bridge I was looking at to keep it from being bombed out during the NATO campaign. Kosovo separated from Serbia in 2008, but Serbia still does not recognize it as an independent state.

The people I met on this trip knew the history of their region deeply. It was not uncommon to hear references to the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires in daily parlance. They were also quick to point out their own country’s failures as well as to note their personal shortcomings. This was in such stark contrast to the American way (point the finger, don’t admit weakness) that it was disarming.

Maybe this behavior was just a part of accepting and reckoning one’s place in the nation-state food chain, of which everyone was painfully aware. As Americans, we’re safeguarded by our own privilege as leaders of the free world.

The Belgrade International Theatre Festival (BITEF) was celebrating its fiftieth year. The theme of this year’s festival was “On the Back of a Raging Bull.” From the program:

Half a century ago, when Mira Trailović and Jovan Ćirilov conceived BITEF, Belgrade, Serbia and Yugoslavia were on ‘no man’s land,’ between the two parts of the ideologically deeply divided Europe and the world as a whole: on the boundary between the Western and the Eastern Bloc. Among other things, it enabled BITEF to become, on a worldwide scale, a singular meeting and exchange point of artists who could hardly come together in a different context. … When the Berlin Wall fell we believed with a great deal of sincere enthusiasm that it meant the end of ideological divisions, and even the ‘end of history,’ but it turned out that, historically speaking, it was a very short-lived illusion. Of late we have become horrified witnesses to the rage of the bull which carried away Europa on its back in the ancient myth. … Europe is splitting up again, digging trenches and putting up barbed wire fences. Serbia and Belgrade are in a similar position again: as a boundary—except that this time it is the boundary between the rich and arrogant North and the poor and impotent South, the center and the periphery, the societies which close up and protect their interests and those which are a transit path for a sea of desperate and helpless people, refugees from the Middle East and Africa.

We watched four shows here. Only Mine Alone by Ana Dubljević and Igor Koruga was a Serbian contemporary dance show about depression and its societal taboos. Riding on a Cloud by Rabih Mroué, is a one man show inspired by and starring his brother, who at age seventeen was struck in the head by a sniper bullet in an attempted assassination during the Lebanese civil war. The Patriots by Jovan Sterija Popović, directed by Andraš Urban was a large-scale show, at the Belgrade National Theatre. It had a lot of regionally specific humor and references. It semi-reenacted the quick succession of occupations in the region and how a group of self-proclaimed patriots kept changing their political allegiances to always end up the victor. It’s depiction of the shifting alliances in times of political change and turmoil is extremely resonant in this region of the world. I kept hearing again and again that many people who did very well for themselves under communism are now doing just as well today. This was kind of a mind fuck.

The Ivan Zajc Croatian National Theatre’s On the Grave of Ignorant Europe by Sebastijan Horvat and Milan Marković Matthis, directed by Sebastijan Horvat was the festival closer, and it played at a beautiful modern theatre space across the river in the city of Zemun. Because the Croatian Academy of Science and Arts did not grant official rights to adapt for the stage, this piece was a loose adaption the very popular Croatian novel, Croatian Rhapsody by Miroslav Krleza. A husband, wife, son, daughter, grandma, nanny, and family friends gather for dinner in a large, ornate dining room. A butler walks in and out, setting up for the meal. What ensues is a Who’s Afraid of Virgina Woolf type evening, replete with twisted parlor games, unhinged behavior, and a whole lot that I found offensive but have no idea how to begin to explain. Suffice to say misogyny on and off stage is not uncommon, and many shows we saw contained things we would not see on US stages today.

Photo by Jamie Gahlon.

We had the pleasure of attending and livestreaming a two-day conference, “BITEF and Cultural Diplomacy: Theatre Festivals and Geopolitics,” that was produced by the festival and the UNESCO Chair in Cultural Policy and Management of the University of Arts in Belgrade, Serbia. Returning to our hotel by cab, the driver pointed out an overflowing refugee center—a line of people from Syria wound out the door and down the sidewalk.

Stop 3: Bucharest, Romania

Landing in Bucharest was a sweet relief after the frenetic pace of Belgrade. The capital of Romania, with roughly two million inhabitants, it’s the sixth largest city in the European Union. The city is a mix of art deco / Bauhaus, neoclassical, and communist era architecture and it’s breathtaking. It used to be called “Little Paris,” and it was easy to see why.

A short walk down Calea Victoriei (Victory Avenue), where we were staying, was a monument commemorating the revolution. It looks like an iron head skewered on an obelisk. There was red spray paint dripping down one side and I couldn’t tell if it was part of the original design or an apt afterthought. Counter to other peaceful Eastern Bloc revolutions, Romania’s did end in violence. In December 1989, in one hour’s time, Communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu and his wife Elena were tried, found guilty, and executed in a public square, ending forty-two years of Communist rule.

Romania has been a member of the European Union since 2007, and I got the impression that folks there were better off than in the places we came from. There was no festival time out in Bucharest, but plenty of people to meet thanks to our host, Iulia Popovici.

We met Simona Cuciurianu and some other Romanian theatre artists at Point, a new privately funded (which is almost unheard of) space featuring a small theatre, bar, and gallery space. We talked about HowlRound and they told us a bit about the current scene. Performance space is hard to find. An actor/director in attendance was trying to create a shared workspace and studio called ArtHub, but acknowledged that sustainable funding was a challenge. The national theatres and the well-resourced theatres don’t seem interested in challenging work (this was a common refrain in every place we visited). They continue to employ the “gold generation,” and there isn’t room yet for the younger folks who might be less inclined to make mainstream fare. Independent theatre companies are eligible for subsidy by the government but only on an annual basis, so it’s hard to plan for anything long-term. And it was commonly acknowledged that, while outright censorship is gone, money only goes to projects that have a certain level of acceptability in the government’s eyes. Simona’s dream for Point is to create a new writer’s theatre, but finding Romanian playwrights that fit the bill has been harder than she thought, partially due to a lack of available training.

We went to dinner with an actress at an old communist private club where we were told not to take pictures. We talked about the US election and I said (with too much confidence) that there was no way Trump could win. She talked about watching other countries in Europe turn increasingly nationalist, and her own fear that “Europe is going in the wrong direction.”

That night we watched Typographic Majuscule written and directed by Gianina Cărbunariu (for more on her read this interview). Based entirely on records found in the Romanian archives from the Securitate/secret police activity and surveillance during communism, the show examined the life of a teenage boy after he is caught writing dissident statements in chalk in his neighborhood in 1981. It was commissioned as part of a larger project to explore the legacy of the secret police in the Soviet bloc during communism (Bela Pinter’s Our Secrets, which just played here in Boston at ArtsEmerson is another such project).

We went to the Green Hours to see Gadjo Dildo created by Giuvlipen Theatre Company, directed by Mihai Lukacs, starring Elena Duminică, Mihaela Drăgan, Zita Moldovan. While entirely in Romanian with no translation it was still easy to follow. The Roma are the largest minority group (or second largest, depending on who you ask) in Romania. They are still extremely marginalized and fighting for recognition in the arts and otherwise. This show was created by and starred three Roma women deconstructing stereotypes of Roma women through cabaret style song and dance. Giuvlipen Theatre Company is the only self-proclaimed feminist theatre group in Romania.

Our Daily Hunger directed by Radu Apostol and created by Replika Center of Educational Theatre ensemble was an immersive show which cast us as guests to a full dinner in honor of a late philanthropist who did much to try and combat hunger. Through the course of the show the audience is asked to reckon with their own moral compass and belief systems through a series of interactive activities.

We had dinner with the Center’s founders and makers: Radu Apostol (director), Katia Pascariu (actress), Viorel Cojanu (actor), and Mihaela Radescu (actress). Against all odds, this collective found a space, rented it, successfully crowd-funded for a roof repair, and have been operating Replika Center as a theatre venue since February 2015. From their website:

The space was conceived as an independent, interdisciplinary space, promoting the collaboration between professional artists and members of vulnerable communities and encouraging a theater for young audience, deeply involved in our society.

At dinner Katia and Radu recalled that the transition from communism to democracy was not without hardship. They commented that while Romania is no longer third world, it’s not first either—they agreed on second world. On the way back to the hotel, we got to a roundabout and Viorel pointed to a cross in the middle, “Many people died here during the revolution.” Radu added that the whole roundabout used to be consumed by a big platform that had been erected to hold a monument of Ceaușescu, at his request. However, despite three or four different attempts, he had never been happy with how the monument looked, and kept tearing it down and rebuilding it. In the mid-nineties it was finally demolished, opening the street to traffic.

Through the course of our stay, we met Nico Vaccari and Sinziana Koenig, founders of Teatrul Béznă, an Anglo-Romanian theatre collective dedicated to challenging inequality. A Brit of Italian lineage and a Romanian who met in drama school in London, they have a unique perspective on the local scene. Against original expectations, they settled back in Bucharest because they felt that their work (political, feminist, engaging issues like sexual violence) would have more direct impact there. And so far, money for projects has eventually materialized too. They brought us to MACAZ Bar Teatru Coop to meet one of the founders, director Davey Schwartz. It was a super funky bar and black box theatre space that opened last January and is so far doing really well—turning a small profit and providing much needed space for political action, activists, and theatrical events too. Davey talked about the originating impulse as two-fold—one, to solve the space problem, and two, to give some of the group steady jobs. They are structured as a coop, so everyone in the collective has equal shares. They run the space and operate non-hierarchically. Davey explained that in Romania there remains deep suspicion of any collectivist tendencies post communism, which makes their intentionally horizontal structure that much more radical. On the way out we noticed words painted on the wall in huge white letters:

In Acest Spatiu Nu Sunt Tolerate Atitudinile Rasiste Homofobe Sexiste Clasiste

In this space we don’t tolerate racist, homophobic, sexist, or classist attitudes

To see this on a wall, in a public space, in a country that does not even recognize homosexuality and has barely scratched the surface of gender inequality, is mind-blowing. The artists are leading the way.

Stop 4: Festiwal Konfrontacje Teatralne, Lublin, Poland

When we touched down in Warsaw, the temperature felt like it had dropped fifteen degrees. We rented a car and drove two-and-a-half hours southeast to Lublin, the ninth largest city in Poland with a population of 350,000. In the car we heard two Alanis Morisette songs on different radio stations, which felt really appropriate. Through the thick fog huge churches dotted the little towns along the highway—we had entered Catholic country. Later someone said that the Poles replaced communism with Catholicism and credited that choice with creating their solid economy. Poland is the only country in Central/Eastern Europe that didn’t collapse in the recent economic crisis. It’s also huge in comparison to its neighbors, and has turned politically to the extreme right in recent years, with other countries following suit. A few days before we arrived, women successfully protested against a proposed total ban on abortion. Throughout the festival some women continued wearing all black in solidarity with these efforts.

The Konfrontacje festival is in its twenty-first year, and is curated by Marta Keil and Grzegorz Reske. Marta wrote a fantastic piece for HowlRound on the state of Polish theatre last December. The theme for this year’s festival was “Autonomy Institution Democracy.”

As public arts institutions, festivals have very precise responsibilities, obligations and roles to play—both in relation to artists as well as to their public, at local and international level… One of the core aims of performing arts festivals is their endless searching of new, original ways of formulating and understanding theatrical language, as well as developing a discourse which would enable the artists and the audience to talk. Festivals should provide artists with the conditions in which they can work and develop their practice and to stimulate the free flow of people, works, concepts and ideas. Festivals are responsible for discovering new phenomena, movements, ways of thinking and producing the arts, as well as becoming open to ever larger and more diverse groups of audiences….In our view, a festival should create the space for independent exchange of thoughts and experiences, offering artists and their public room and time to think, to experience, to talk. It should leave however additional space for unexpected encounters, coincidences—and clashes.

Broadly, there are loads of festivals in Poland and throughout Eastern Europe. Curators program the shows, and some, like this one, have co-curators. Curating is often not a full-time job, but rather balanced with other gigs. Every show that we saw here at Konfrontacje was artistically excellent and thought provoking. The two curators managed to program shows that were perhaps more closely aligned to our Western aesthetic sensibilities.

On the morning of October 8, when the Hungarian government unceremoniously shut down the country’s major left-wing newspaper, we met Zenkő Bogdan, a Romanian currently based in Budapest, at the time serving as Eastern European Project Manager for the Center for International Theatre Development. She lent valuable context to our time in Poland.

We livestreamed a lecture by Bojana Kunst on her book Artist at Work: Proximity of Art and Capitalism, which was newly translated into Polish. This event was part of a launch of the Performative Centre, a new program of the Eastern European Performing Arts Platform (EEPAP) that shares many deeply rooted HowlRound values:

Its mission is to create a space which enables an open, animated dialogue, not subordinated to the market principles and free from hierarchical academic structures. The Centre’s main goal is to offer the artists, thinkers and culture workers time and space to think and practice instead of forcing them to produce a new event, “a cut-and-dried commodity.” … the Centre offers a space which is focused on developing the choreographic and performing arts practices and, by doing so, on strengthening a critical reflection around them in the social, political and economic context.

War and Peace by Gob Squad invited the audience to a salon to discuss Tolstoy’s War and Peace. Four audience members sat at a table on stage and answered questions relating to War and Peace the novel but also to war and peace as concepts. Throughout the salon discussion, we were presented “distractions” that related to the evening: a fashion show of characters from the book, a moving harp rendition of John Lennon’s “Imagine”—the distractions cleverly built on each other, and by the end of the night we were all in.

Next up was a concert revue Songs From My Shows by Ivo Dimchev—imagine a more tawdry and Bulgarian Taylor Mac. Parental Cntrl by Ground Control, was directed by Ferenc Sinkó and created in collaboration with kata bodoki-halmen, Kinga Ötvös, and Krisztina Sipos. It explored through movement and music three Generation Y women and their relationships with each other and to their families. Penny Arcade starred in a solo show, Longing Lasts Longer, about the dangers of gentrification, mass media, and mind control (the “integrated spectacle”). Time’s Journey Through A Room by Toshiki Okada / Chelfitsch, from Japan, presented a man trying to begin a new relationship after losing his wife in an earthquake. Birdie by Agrupación Señor Serrano of Barcelona, Spain, integrated video from The Birds with live video of action on a miniature set. As a jumping off point the show used a real-life photo taken in Melilla (a Spanish autonomous city located on the north coast of Africa) of people mid-swing on a beautiful golf course while not far behind them, newly arrived refugees climb over the top of a tall metal fence. Incredibly precise and timely, the show asked questions about migration, fear, hate, politics, and our own humanity.

Experiencing the rise of fascist and isolationist ‘America First’ rhetoric, I’ve been reflecting on the role arts and culture can play in fighting repressive government and bolstering democracy.

Theatremakers I met commented again and again that politicians aren’t acting responsibly for the people of their country, and that the ruling government remains corrupt. Everyone knows it, and everyone seems to accept it. One actress said she felt that most people still (incorrectly, to her mind) see the government as an apparatus entirely separate from themselves; a holdover from communist times, that despite the revolutions, the new governments that emerged are something the people aren’t able to impact. They stand apart. As much as it’s hard to admit, hearing these sentiments pre November 8, I felt some small sense of satisfaction that my country doesn’t operate like that; we have a functioning democracy by the people for the people. Reflecting post-election, I’m not sure I still feel this way.

Life under this new US administration has given me ample opportunity to feel a bit closer to the people I met and the world I encountered in Eastern Europe. Experiencing the rise of fascist and isolationist “America First” rhetoric, I’ve been reflecting on the role arts and culture can play in fighting repressive government and bolstering democracy.

Last month, following the mobilization for the Women’s March on January 21, Romanian citizens took to the streets to protest the government’s passage in the middle of the night of an ordinance that weakened anti-corruption laws. These protests were the largest in the country’s history—and they worked! Four thousand miles away and across a cultural divide, I felt connected through resistance, resilience, and creative expression. Next month, when we return to Eastern Europe to present the World Theatre Map at the IETM Bucharest Plenary Meeting, I look forward to meeting again with fellow theatre practitioners, curators, and producers to support one another and share innovative models of collaboration to shape and reshape culture and society.

***

Unless otherwise indicated, all photos by the author.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I enjoyed reading about your international playgoing, and seeing the photos. "Opernball" sounded especially interesting. There already may be something like this, but there should be more international festivals, so that more American audiences could be exposed to the kinds of works you described. It might be a bit more than professional theaters are willing or able to undertake, but academia might be more up to the task. Perhaps you could compile and edit a volume of some of the plays you saw?

Thank you for this report on a part of the world that I love, having toured the Balkans several times with co-productions by Blessed Unrest (NYC) and Teatri ODA (Kosovo). One correction, or perhaps a difference of opinion: Serbia’s south is not bordered by Macedonia and Albania, but by Macedonia and Kosovo. Though Serbia does not recognize Kosovo’s independence, 111 UN member states do, including the US and virtually everyone else but Serbia, Russia, their close allies, and a few other countries that fear separatist movements of their own.

Thanks again for your work!

Hey Matt, Thanks so much for pointing this out. We have no difference of opinion--I have amended my text accordingly to indicate that Kosovo, while disputed, is to the south. Thank you for commenting!