On the surface, Burrnesha is not as dark as Stiffler. It is a truism that in many of Neziraj’s works, there is always some half-hidden ambiguous redemption (even The Handke Project has this)—and this piece is no exception. Some redeeming factor allows the “victims” of the stories (I use the term loosely) to claim back some control.

Sose lives as a man in the Albanian mountains until Edith convinces Sose to come to London and talk about being a sworn virgin on television—as if she is a living exhibit. Edith is oblivious to her exoticizing attitude towards Sose. Even worse, when Julian hears about Sose in London, he decides he must have her on his show to boost his flagging drag career. But because Julian doesn’t think Sose’s story is enough to wow London audiences he wants Sose tell the audience she went to prison after murdering someone. According to Julian, “Art is the lie that saves us from reality.”

Julian’s attitude toward Sose is one of patronizing welcoming. He has all the power, yet it becomes apparent that he is the one who is ill-at-ease and insecure, not Sose. In confirmation of this, Julian exasperatedly tells Sose that she is the real drag queen, not him. But Sose is not in drag. This moment in the play is terribly important and appears to be the center around which everything else is based. Sose is a sworn virgin so she can survive, something Julian fails to understand.

The central message—that women who become sworn virgins are courageous and brave—is powerfully underlined in the play. Erson Zymberi, director of Burrnesha and artistic director of Gjilan City Theatre, told me that thinking about sworn virgins kept him awake at night. He refers especially to one story he heard where someone was in terrible pain during her period and had to hide her anguish from the male companions she was with. In his confession lies buried a deep understanding of what sworn virgins have to go through and what they have to give up.

This contrasts with Julian’s attitude, and though he’s a fictional character, he probably represents a response that is commonly experienced by sworn virgins. In comparing Sose to a drag queen, Julian totally misunderstands Sose’s cultural background and the context for becoming a burrnesha. In order to explain it to himself, he compares Sose to the closest thing from his own Western culture: a drag queen. Thus, Sose is othered and her experience explained away using an inaccurate Western contextualization. Sose’s story is not so much wrested away from her but transformed and made alien into something else. Neziraj admits that this idea of the West reframing and recontextualizing other cultural experiences to make things make more sense to them is a preoccupation in his work.

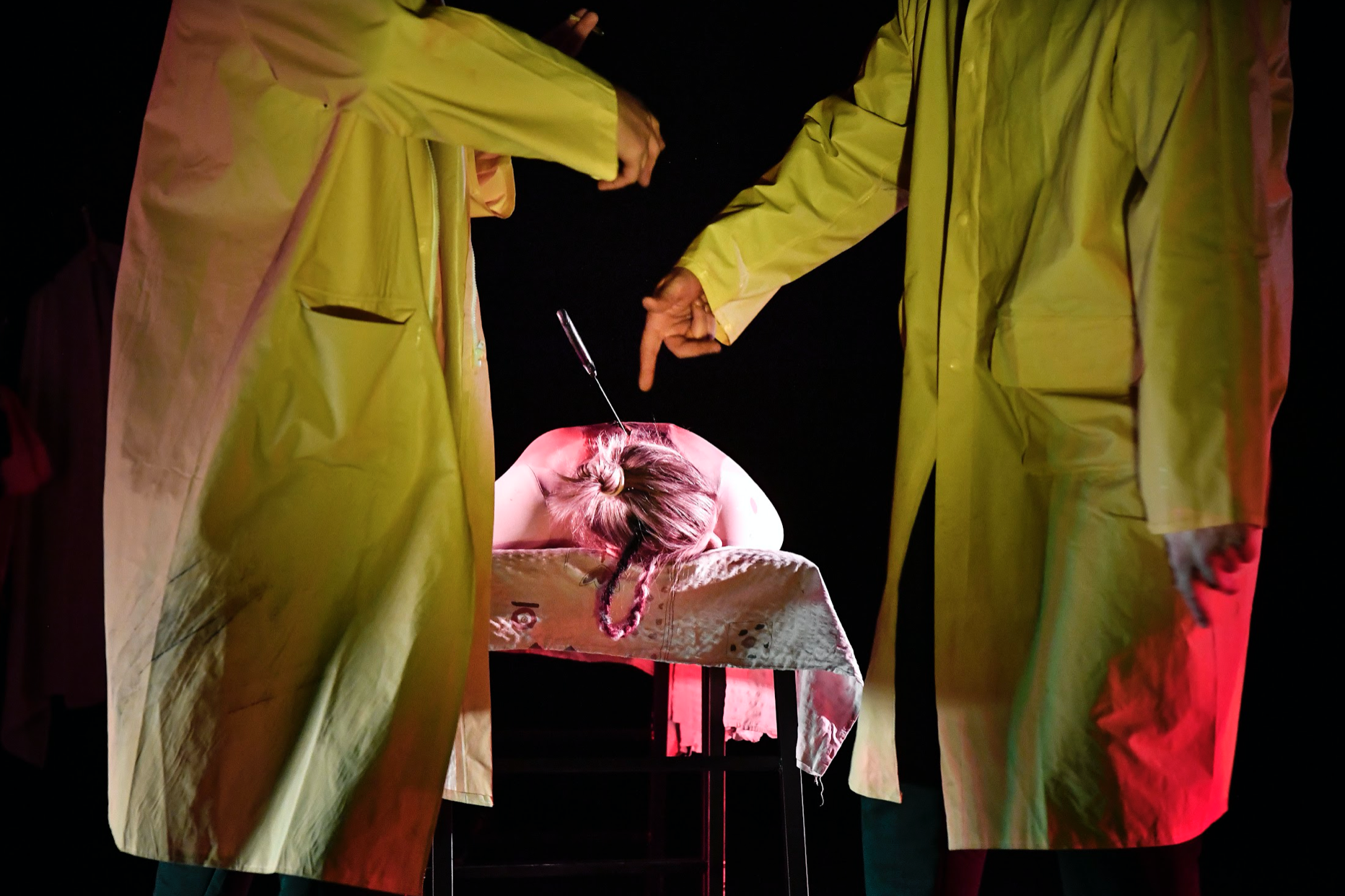

Zymberi explores how the story is told and mistold through the use of microphones and a TV show format. Sose and Edith face off against each other on the mics across a narrow stage space (reformatting Oda Theatre’s playing space drastically). The effect is reminiscent of a catwalk or a lecture space as the audience, sitting on raised seats, might feel they are being called upon to judge Sose. Sose is made into a spectacle and, one could argue, is being put on trial. Is she interesting enough for a Western audience?

But for a really clever and brilliant moment, Zymberi turns the tables on Julian and gives him a taste of what it feels like to not be in control of his story, the mic pointed at him demanding that he speak because the security of his life depends on it.

At the top half of the stage is a mirror, angled enough so that only the back bottom halves of the actors’ bodies (almost from knees down) are reflected. The effect is to encourage an audience to look at the characters when they don’t know they are being looked at in an act of inconsiderate voyeurism. Zymberi explained that he was interested in exploring Sose’s inner and external lives—how she sees herself on the inside and how she is seen on the outside. It is the outside that Julian and Edith, to a certain extent, try to control.

The play then makes a move to explore the psychogeography of such spaces because, of course, the inner and the outer are never and can never be separate zones. Thus, the playing space also becomes Sose’s home, Soho Theatre, the TV studio, and an oda e burrave—a room where Albanian men meet. There is nowhere for any of the characters to hide. Zymberi creates a playing space where each character’s psychological experience of the other’s behavior is apparent and exposed. This is seen in moments like when Edith kisses Sose and dares her not to feel anything or when Julian finally understands how he has wronged Sose and travels to Albania to seek “forgiveness.”

In total contrast to Stiffler and Hava’s circumstances, Sose is able to take better control of her story in a kind of moral cleansing. When Sose forgives Julian, the mic is used as if it is a gun causing Julian to think Sose is going to kill him—a reference to Julian’s earlier attempt to fabricate Sose’s life story. Instead of shooting Julian though, Sose aims the gun at a deer that is supposedly behind him. But for a really clever and brilliant moment, Zymberi turns the tables on Julian and gives him a taste of what it feels like to not be in control of his story, the mic pointed at him demanding that he speak because the security of his life depends on it.

What have these plays got to do with gender violence in the Balkans (specifically Albania and Kosovo) and in wider global societies as a whole? Both shows make it clear that gender violence is a societal phenomenon and use that to question who gets to tell whose story and how. These stories have both been able to reach people in different ways. Though critical of Kosovan society, because of its success Stiffler was invited by the country’s Ministry of Justice to take part in the country’s sixteen days of activism against gender-based violence (10-25 December 2022). Neziraj shared that a Balkan woman from New York happened to come and see Burrnesha when it premiered in Prishtina. Immediately afterwards, she found Neziraj and Zymberi and said that the play helped her make sense of her own life, as it helped her to understand that she is a Burrnesha as well. Both these narratives have reached and touched people in unexpected ways.

Basha told me that her grandmother always warned her about men and boys when she was growing up: “Boys can hit you. Men can kill you. Police won’t care. Doctors will judge you. Judges won’t believe you. Now go out and live your life.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here