“That was something, wasn’t it?,” my dad mutters with a forced nonchalance.

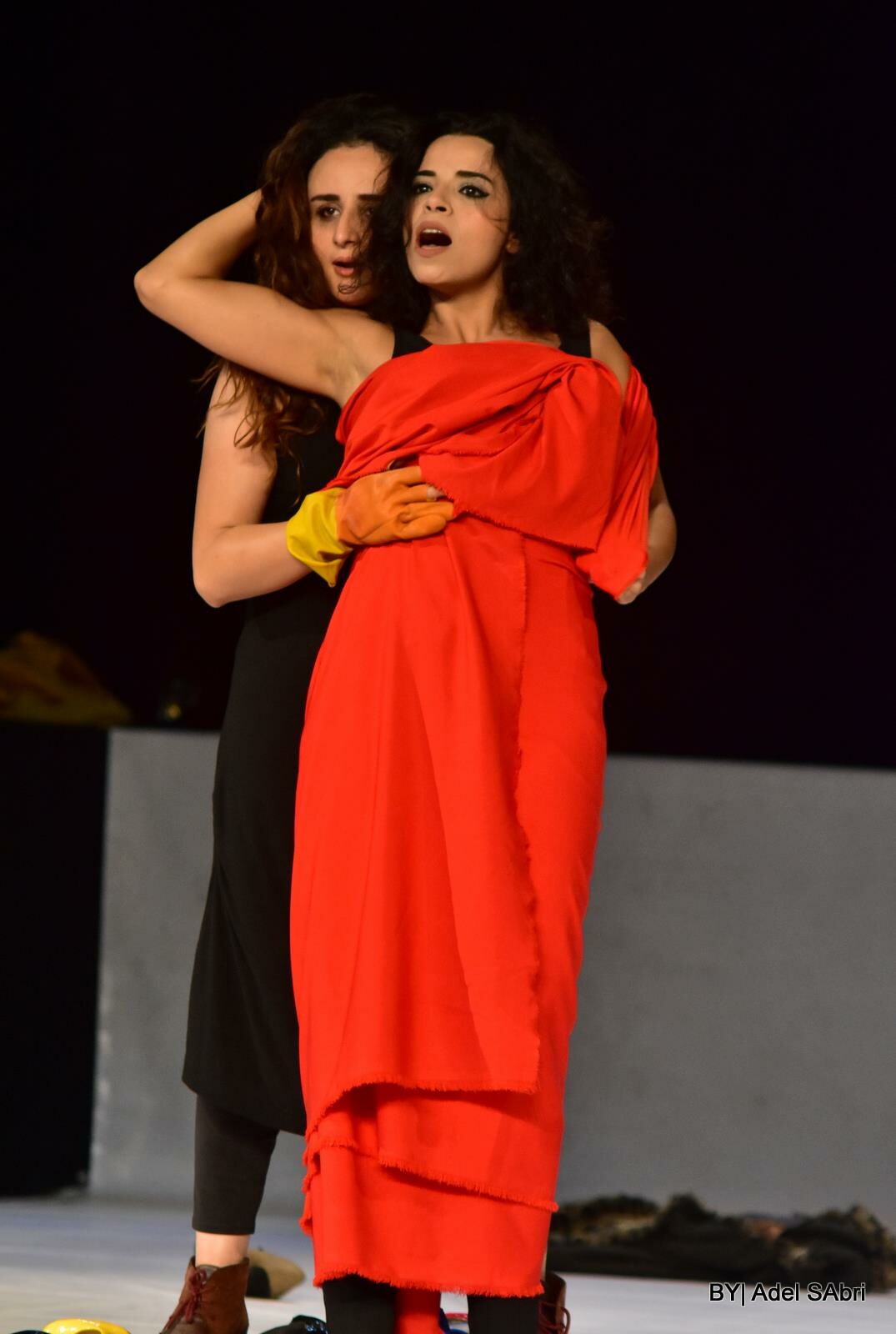

We are driving out of the parking lot of El Gomhoureya Theatre in downtown Cairo. It’s 9:55 p.m. on the 18 of September, day nine of the Cairo International Festival for Contemporary & Experimental Theatre (CIFCET). My dad had decided to join me at the last performance of the evening, a Moroccan adaptation of Jean Genet’s 1947 one-act play, The Maids, by Iraqi director Jawad Al-Assadi. In this production of the Genet classic, the tension is high as the two maids (Jalila Al-Talmasi and Rajaa Khirmaz) take turns pretending to be their mistress. Their relationship oscillates frantically from beat to beat: one minute, one of them sadistically attempts to choke the other to death; the next, they straddle each other, discussing the mistress’s last sexual encounter. It’s undeniably homoerotic.

My father is, of course, right. Al-Assadi’s adaptation wouldn’t be flagged as obscene or graphic on a Berlin or New York stage; yet here in Cairo, as a part of the Silver Jubilee programming of a state-sponsored festival, it’s something.

“I’ve never seen subjects like that discussed on stage before.”

I keep my amusement at his referring to queerness and female sexuality as “subjects like that” to myself and tell him, instead, that sexuality is not exactly a unique subject in theatre, even though it might be in this city.

I’ve explicated the elephant in the room on this ninety-five-degree night. Two blocks later, still awkwardly quiet, we pass by a traffic light. A decaying billboard close by, which has probably been there for over a year, announces that Arabs Got Talent will be accepting new auditions this summer. On one side of it, a huge sticker quoting Islamic Hadith reminds women to cover up. On the other, graffiti of President Sisi’s face adorns the wall. I ruminate over the conversation with my dad. It’s not that this is the first time censorship has come up since the beginning of the festivities. Yet the conversation with my father is the one that hits me most because I find his thinly veiled internal conflict so emblematic of the paradoxes of the Arab middle class: wanting to engage with cosmopolitanism and all it offers in culture, yet being flustered at the first threat to a conservative worldview. That paradox is in the very billboards before us. The signal turns green.

I ponder over the thing I have enjoyed most about the festival so far, which is the apparent absence of censorship. A lot of the performances (which are often graphic, explicit, or political) wouldn’t have passed the censors here if they were being presented by an Egyptian company as an Egyptian production, or if they were being presented outside the festival.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

[How can artists leverage the constraints of censorship to create innovative dramaturgies rather than approach the constraint as a hurdle?]

i think this is a question that is essentially at the heart of all theater making. how to take the challenges you face on a particular production or with a particular budget or space, and turn those into opportunities. And I think you're right, some of the best art has come during times of monarchal repression.

[How can we maintain what’s compelling about these dramaturgies beyond censored theatrical environments?]

I find this to be a very intriguing question, how to make something resonate when you remove its context. Do pieces created under this law of censorship, for example, lose their potency once that censorship is gone? I would be so interested to see some of the more controversial pieces from this festival recontextualized.

Yes, I am particularly interested in looking at how Egyptian theater created outside the context of the festival resonates if it travels to festival contexts elsewhere. Do the artistic choices born out of constraints on speech resonate elsewhere, or do they ultimately come off as arbitrary/confusing?