A Home of Their Own

the Playwrights’ Center

In a lively Minneapolis neighborhood located near the Mississippi River, the University of Minnesota, and an energetic Somali community stands a renovated church, home to the Playwrights’ Center, an organization that serves the development of new voices in the American theatre. For over forty years playwrights have come and gone; because of the Center many have stayed in Minnesota while their work has been produced all over the world. Others have moved on while maintaining personal and professional ties to the Center.

Mission and management have changed, too, shifting with the times, the available money, and the needs of the field. During all those years, the Playwrights’ Center has become an institution and part of a network of organizations, most of them located on one or the other of the coasts.

The Playwrights’ Center helps each of its playwrights develop skills, release an authentic voice, and create a professional network leading to local, national, and international productions.

But here in the heart of the Midwest, far from any coastal vibe, The Playwrights’ Center helps each of its playwrights develop skills, release an authentic voice, and create a professional network leading to local, national, and international productions.

The Center operates with a staff of ten who together administer:

- The Jerome Fellowship Program that annually supports the work of four emerging American playwrights;

- The McKnight Fellowship in Playwriting that recognizes two playwrights whose work demonstrates exceptional merit and whose primary residence is in Minnesota;

- The Many Voices Fellowship, awarded annually to two early-career playwrights of color, and the Many Voices Mentorship for two beginning playwrights of color;

- The McKnight National Residency and Commission program to commission and develop new work;

- The McKnight Theater Artist Fellowship recognizing Minnesota-based theatre artists other than playwrights whose work demonstrates exceptional artistic merit.

The Center also runs PlayLabs (an annual weeklong festival of new plays written by Center Core Writers) and the Ruth Easton New Play Series (in-depth development workshops for Core Writers with public readings).

In addition, the Center runs a Core Writer program, an Affiliated Writer program, a college and university new plays program, a membership program serving 1,500 member playwrights, and an internship program. Its website provides educational resources and opportunities to playwrights nationally and internationally.

The Center describes itself as the “artistic home for 1,500 member playwrights, four Many Voices Fellows and Mentees, four Jerome Fellows, six McKnight Fellows, and twenty-four Core Writers.” Jeremy Cohen, the producing artistic director, keeps all this activity in motion. For Jeremy, “Our greatest societies have turned to our artists in times of war, of poverty, of hate crimes, of devastation.” He wants the Center “to restore the artists to a place of vision and leadership. Through playwright-driven development workshops, to building long-term and meaningful connections with producing theatres around the globe, to writing resources available for anyone who wants them. And by paying all of the artists who are working on these initiatives so that we can help sustain them to continue this important work.”

What do playwrights expect to find at the Center? Are they getting what they need? Does it, in fact, help playwrights to hone their skills, develop their voice, and find production opportunities? Do the writers receive the support they expect? Does it open up opportunities for production? We, both of us long-time theatre practitioners and scholars, decided to ask some playwrights to talk about their experiences. We began by talking to someone whose involvement with the Center goes back to its very beginnings.

Our first interview was with playwright Barbara Field, one of the three Center founders, one of five original members, and a current Core Writer. She is the author of a cherished adaptation of The Christmas Carol that was a Guthrie Theatre tradition for thirty years. She also adapted Great Expectations for the Seattle Children’s Theatre. She won an LA Drama Critics Award in 1996 for Boundary Waters at the South Coast Rep, and is the author of numerous original plays. She created the libretto for Rosina, commissioned by the Minnesota Opera and due to be produced at the dell’Arte Opera Ensemble in New York, in August 2015.

We talked with Barbara over lunch at a local bistro, the French Meadow, on October 29, 2014. She told us how the Center came to be. In 1971, three students, Tom Dunn, Erik Brogger, and Barbara, took Charles Nolte’s playwriting class at the University of Minnesota. They were casting around for a way to have their work produced. According to Barbara they “needed an umbrella to work as leverage to get our plays done.” With playwrights Jon Jackoway and John Olive, they registered as a not-for-profit calling themselves the Minnesota Playwriting Organization.

Suddenly, Barbara says, their work was taken seriously. (“You’re an entity!”) Their first one-acts were produced at the University of Minnesota Student Union. The Walker Art Center then offered them two nights for short plays and designed a gorgeous graphic. They were even reviewed!

It dawned on them, at that point, that since they were getting such attention, “possibly they needed to make the plays better.” And that need defined the mission of the early Playwrights’ Center.

In order to grow, the Center needed a venue. At first it was located in an old fire station on the West Bank of the University of Minnesota. Tom Dunn, knowledgeable about funding, ran the Center. According to Barbara, “he was the spitting image of Paul Bunyan.”

Barbara left the Playwrights’ Center in 1974 to become literary manager for Michael Langham, artistic director at the Guthrie from 1971–1977, but returned to the Center in 1980 just as it was becoming clear that, after a series of temporary locations, the Center needed its own space. Tom Dunn hoped to buy and renovate the Olivet Church in what was then a rather “iffy neighborhood.” Waring Jones, the Center’s great benefactor, assumed the mortgage and ultimately gave the building to the Center.

We asked Barbara to assess the Center’s contributions to the theatre. She sees it as being of major importance to the local theatre community, and, along with other play development organizations such as New Dramatists and the Lark, important to the national theatre as a locus of script development.

She has observed major changes in the Center, including:

The introduction of dramaturgy, “a second eye,” as a way of improving a script;

The commitment to training actors to deal with new scripts;

The effort to pair news scripts with artistic and production directors;

The focus on getting new scripts past the workshop phase and into production seasons.

Finally, the Center brings creative people to the Twin Cities. Barbara is sure that “We have more playwrights here than we have a right to!”

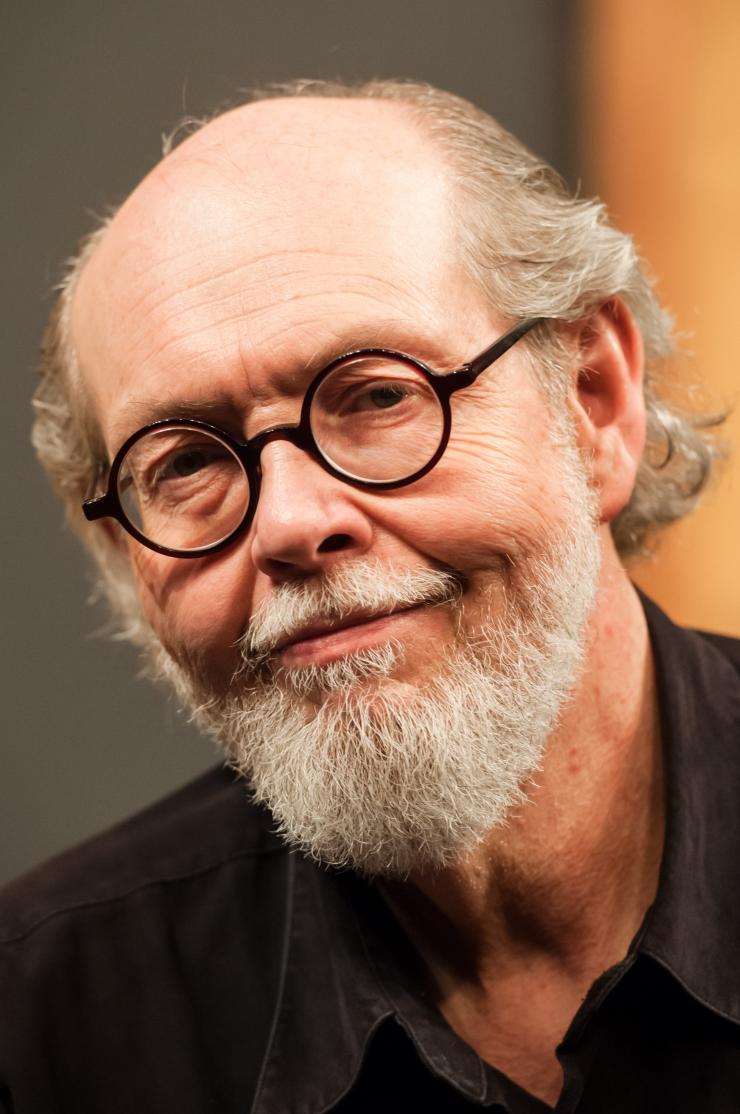

Jeffrey Hatcher

Jeffrey Hatcher picks up the story of the Center’s development. We interviewed Jeff at dinner after seeing a production of his one-man show, Jeffrey Hatcher’s Hamlet at the Illusion Theatre. Jeff’s work has appeared on Broadway, Off-Broadway, and at major theatres all over the country and abroad. He writes for both television and film. He wrote the screenplay for the 2004 movie Stage Beauty, based on his play Compleat Female Stage Beauty. He also wrote the screenplay for Mr. Holmes (2015), directed by Bill Condon and starring Ian McKellen as Sherlock Holmes. In 2000 he published The Art and Craft of Playwriting.

Jeff came to the Playwrights’ Center as a Jerome Fellow in 1987. At the time, the Jerome was $5,000 for the year—not a fortune even then but enough to lure him to leave New York for Minneapolis. Following his Jerome fellowship, Jeff served as the Center’s Lab Director from 1989 to 1994. He is currently a Core Writer with the Center.

We asked Jeff what the Jerome and the Center meant to him back then. They were, he said, a “stamp of approval,” proof that “somebody likes you, somebody thinks it’s good enough to merit continuing on.” The Jerome signified the Center’s investment in the writer not necessarily in one particular script. And “it was really nice to find a group of people that you can talk to about the theatre, that you can bounce ideas off of. The Playwrights’ Center connected you to other playwrights.” The weekly Monday night readings “created the rhythm.” After every reading there was a discussion, and then afterward the playwrights would go out to a bar and talk to the writer. In his seven years in New York he had never had that experience of community.

We asked Jeff what has changed since his time at the Center. The recession of 1990–91 was a major financial shock and challenged the Center’s programs. In order to remain solvent, the Center considered cutting the number of workshops and readings; people questioned whether they needed to take place every Monday night. Or would it be possible to reduce services to the general membership (which cost all of $35 a year)? Once a service is cut, however, it is tough to restore it. This crisis fore-grounded the Center’s ongoing search for reliable financial support.

Jeff sees the Playwrights’ Center as part of a playwright support network, including the O’Neill, Sundance, and New Dramatists, all of which developed during the 1970s. Such organizations simply didn’t exist before that.

Barbara and Jeff have established major careers over decades. We continued our interviews, speaking with writers at different stages in their careers.

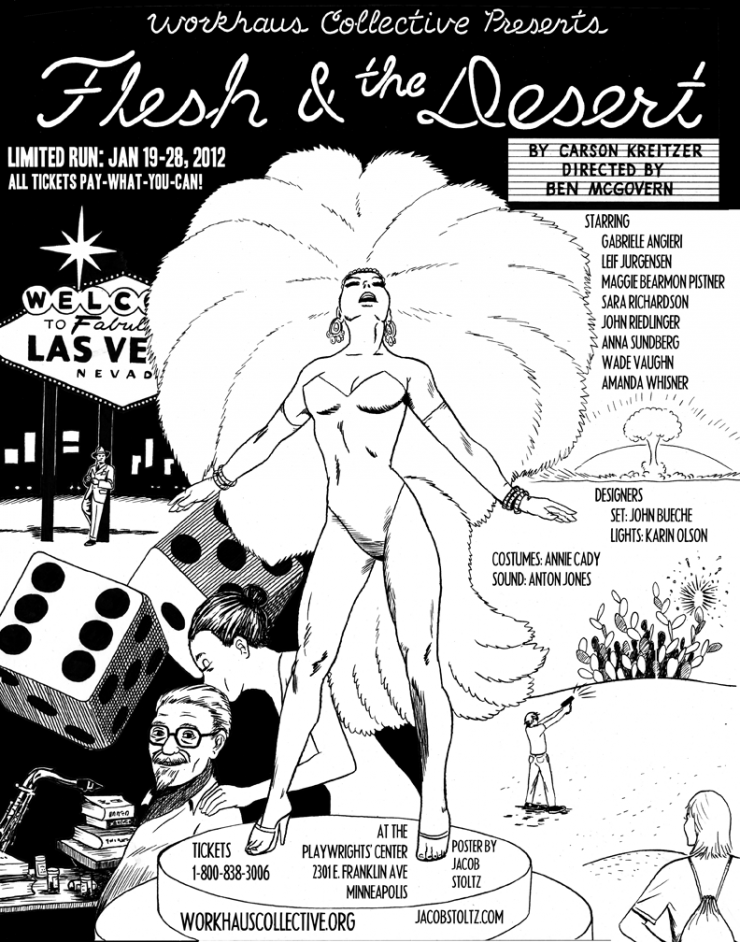

We caught up with Carson Kreitzer between work trips, interviewing her on April 8, 2015, over lunch at Blackbird in Minneapolis’ Kingfield neighborhood. Carson has created a major body of work, including a triptych of plays about women who kill. Her work has been produced in theatres around the country, including The Cincinnati Playhouse, and the Marin Theatre Company. She is a member of the Workhaus Collective, a resident theatre company at the Playwrights’ Center. She is currently working with composer Matt Gould on the book and lyrics for a new musical inspired by art deco artist Tamara de Lempicka and writing a new play for the Guthrie Theatre. Carson has been a Jerome Fellow twice, a Core Writer, and is now on her third McKnight Fellowship. She also serves on the Center Board.

Carson grew up north of New York City. Her academician parents regularly took the family to the theatre and the house was full of show albums. As an undergraduate at Yale, she enrolled in the acting program but discovered in her first scene study class that she really wasn’t an actor. She began directing.

As a director she studied the available material but nothing seemed to reflect her worldview. For example, when directing Genet’s The Balcony, she realized that the whores were never present as themselves, but only in the roles they played for clients. She found that what interested her most was not Genet’s fantastical world of make-believe but the off-stage lives of the women. She staged the play in the round making a place for the whores on the periphery of the space where they lived their ordinary lives— doing their nails, eating, and so forth.

Carson writes mostly about women, like Genet’s whores, whose stories exist on the margins of traditional narratives. These women may not be heroic but they deserve to be heard. She wants to write the “voices that are silenced.”

After Yale, Carson went to New York and won a Jerome Fellowship. The award she received was just over $7,000, half of which went to buy a used car to navigate the Minneapolis winters. Luckily, the following year she got the $25,000 McKnight Fellowship in Playwriting and then a second Jerome a year later.

She left Minneapolis to do an MFA in Playwriting at the University of Texas-Austin but then returned. “The Playwrights’ Center,” she says, “has been my artistic home since the year 2000.” Unlike New York, which offers many opportunities but a splintered community, Minneapolis provides “coherence to your artistic life,” and a chance for intimate connections.

Minneapolis also offers a chance to work with ”an amazing cadre of actors.” She can call on “my people,” actors she’s worked with again and again over the years, who intuitively grasp why “something that is terrible is actually also funny.” Twin Cities’ actors bring “a fierce intelligence” to their work.

We asked her what she has gained from the Center. For Carson the Center has been useful in different ways at different points in her career. At first, it provided the recognition that there was a path she could follow, and a chance to have her writing supported. It was wonderful to be part of a coherent group of writers for continuity and companionship, and also have the ability to “hole up and get work done.” In New York she had been pretty lonely writing in isolation.

Carson credits the Center with helping her develop relationships with theatres; when The Love Song of J. Robert Oppenheimer was workshopped at the Center’s PlayLabs, the brochure went out to theatres around the country including The Cincinnati Playhouse, where Artistic Director Ed Stern selected it for the Rosenthal New Play Prize, which meant a full production with Mark Wing Davey directing. The three of them have sustained a creative working relationship ever since, collaborating on two more productions there, including Behind the Eye, a commission for the Playhouse.

As a Board member, Carson has insights into the Center’s challenges. The two that she identified were scarcity of resources, a problem that impacts most arts organizations, and historic continuity. To address these, the Center recently created the Affiliated Writers program, which allows former Core Writers and fellows to stay involved with the Center through partnership and development opportunities, the chance to teach classes and work with member playwrights, and an online profile on the Center website. For Carson this site is a moving testimonial to the many writers whose lives the Center has touched.

Carson sees herself at an “awkward” career stage—“the barren middle, the desert.” The middle is hard; you still need support, but there are lots of new “emerging” writers claiming the existing resources. You don’t stop needing support just because you are no longer “emerging,” and it is still “goddamned hard to get productions!” There ought to be a good sexy term for people who are in the mid-point of their careers.

Idris Goodwin, a Core Writer at the Center, is an innovative young playwright and spoken word artist whose work is inspired by Beckett and Spaulding Grey, as well as by hip-hop and breakbeat poetry. We interviewed him via Skype on January 7, 2015.

Originally from Detroit, Idris got into theatre because he “liked making things.” He majored in film, video, and screenwriting at Chicago’s Columbia College. He took a theatre course or two but “didn’t get into it.” He says he was drawn into the theatre by accident when “someone asked me to do something,” and he learned by doing.

Eventually he left Chicago to participate in a playwriting workshop at the University of Iowa. After Iowa he earned an MFA in Creative Writing from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. How We Got On, his first play after the MFA, “really clicked,” with both audiences and critics. It was about 1980s teenagers from the suburbs in love with hip-hop. It was chosen for Actors Theatre of Louisville’s 2012 Humana Festival and will soon appear nationally in other venues. His play, This is Modern Art (based on true events) addresses the lives of graffiti artists and asks questions about what constitutes art; it opened at Steppenwolf Young Adults this year. In This Corner…Cassius Clay premiered at the Kentucky Center in Louisville. Idris, who lives in Colorado Springs and is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Theatre and Dance at Colorado College, has also developed work closer to home at the Denver Center. In 2015 Idris was commissioned by Oregon Shakespeare Festival to participate in their American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle.

Idris visited the Center in 2003 and submitted a script for consideration, and although that script wasn’t selected, he was resolved to connect with the Center. He didn’t think he could “consider himself a serious playwright otherwise. “It is all about name; people hearing your name. It’s a badge. You are serious. It is what you want to do with your life.” Idris has been a Core Writer since 2013.

Early last March, the Playwrights’ Center mounted a Ruth Easton reading of Idris’s The Realness about a young student, a tourist in the world of hip-hop and spoken word performance who finds both love and friendship.

We asked Idris how useful workshop productions were. He pointed out that he started out mounting his own work and says he is happy to have institutional support of any kind. He is thrilled when his work is done anywhere. As someone used to producing his own work, he was pleased to be able to make requests of other producers and have them honored. “Workshops have only benefited me,” he says. “Development is the way we live and eat and meet each other.”

When we asked Idris what would help him in his next career step, he responded that he needs time—time and “a room and I need some actors. The Center provides that and much more.” He’d like a wider actor pool. He writes in a hip-hop aesthetic and needs a certain type of actor to bring the material to life. And Idris Goodwin is changing. “My first play,” he says, “was a blatant rip-off of True West. Now I am ripping off August Wilson.”

Rhiana Yazzie, a two-time Jerome Fellowship recipient, didn’t know much about the Twin Cities arts scene when she decided to move to Minneapolis; but she did know that there was a sizeable Native community. A member of the Navaho Nation, Rhiana was interested in learning about a new Native community.

Rhiana has been commissioned by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival to contribute to American Revolutions, a cycle of plays springing from “moments of change” in the direction of American history. She also writes for young people; Chile Pod, written for La Jolla Playhouse, has been performed for 18,000 children in Southern California. She is the founder and artistic director of New Native Theatre, a Twin Cities company “presenting a new way of looking at, thinking about, and staging Native American stories.” We met with Rhiana at the Playwrights’ Center on December 8, 2014.O

Rhiana’s undergraduate degree is from the University of New Mexico. She says with a laugh, that she got into theatre “for the money,” a $400 writing fellowship that committed her to try to write plays.

Finishing school, Rhiana went to work in arts administration, writing grants for East West Players. But arts management wasn’t what she wanted and she started looking around for something more satisfying. She found the Playwrights‘ Center on her own while browsing through Dramatist’s Sourcebook. She applied for and won a Jerome Fellowship.

Rhiana started New Native Theatre in response to her experiences trying to cast her first Jerome Fellowship workshop of The Woman Who Turned Into a Bear, a play intended to be produced with Native actors. There are lots of Native people in the Twin Cities, many of them frequent participants in traditional performance, but they have historically had limited access to theatrical institutions.

Rhiana knows that, “I am writing work that people don’t want to look at or think about yet.” She wants to see the Playwrights’ Center do more to foster the growth of Native playwrights, particularly given its location in the heart of one of the most politically active Native communities in the country. Rhianna is the third Native American to receive a Jerome Fellowship.

Her theatre is part of a small, loosely connected group of Native theatres, but the nationwide number is small. The company does a couple of productions a year and runs classes for Native people, many of whom have never had the chance to do theatre. Rhiana believes that for many Native people, “doing theatre is massively healing.” New Native Theatre’s first project was a twelve-hour Native theatre marathon. The theatre has also commissioned and produced 2012: The Musical!, probably the first full-length Native musical comedy. The theatre is currently working on a podcast about the lives of Native women.

Rhiana Yazzie, a two-time Jerome Fellowship recipient, said the most important thing the Center has done for her is to validate her; she can go into the world wearing ‘a badge of success.’

Rhiana knows the Playwrights’ Center can’t “protect me from reality,” but the staff has been an ally in problem-solving. Rhiana appreciates the investment that the Center staff makes in each individual playwright.

Rhiana says that the most important thing the Center has done for her is to validate her; she can go into the world wearing “a badge of success.”

We joined Kate Tarker for lunch at the funky Seward Café on December 19, 2014. Kate’s plays include THUNDERBODIES, An Almanac for Farmers and Lovers in Mexico, Laura and the Sea, m.a.h. (a museum play), and the ten-minute play Paper Cut. Her next piece, Good Job Horses (A Majestic Comedy), which she co-created with Theatre Forever, was presented at the Southern Theatre in Minneapolis earlier this year. In addition to writing, Kate has mentored high school students and taught playwriting at Wesleyan.

Her path to the Center began with the visual arts. At Interlochen Arts Academy, which she attended during high school, she imagined herself a painter. There, she mingled with a mix of talented people, including some formidable theatre artists who taught her that theatre represented an eclectic amalgamation of the arts. This was a provocative idea.

Postponing college for a year, Kate traveled to the Congo planning to work on an art project; the project quickly deteriorated turning her life “into a surreal play.” She was eighteen and immersed in a culture in which social tensions were high and much was at stake. She began to keep a journal. As she developed an ear for language, her awareness of the ways language serves as an instrument of domination grew.

As a student at Reed College, she participated in lots of co-curricular activities, including theatre, and was invited to attend the Kennedy Center Playwriting Intensive. It was this experience of meeting living playwrights that determined her path.

After graduation she made the pilgrimage to New York where she found a home at Primary Stages/ESPA, and had a reading at the 59E59 Theatres. She was accepted into the MFA program at Yale Drama School, graduating in 2014. Not yet ready to return to New York, she applied for a Jerome Fellowship and came directly to the Playwrights’ Center.

She applied for the Fellowship because “graduate school had gone by quickly and I wanted a chance to slow down and work.” She had a portfolio of short plays that called for more effort; the Fellowship has given her the time to work without being rushed to complete a project.

Although Kate loved New York City, lots of people she admired had worked at the Playwrights’ Center at one time or another, so when she received a Jerome Foundation Fellowship she was ready to sign on.

For her, the strength of the Center’s program is that “it meets you where you are.” She, for example, “came to Minneapolis to hang out with the clowns.” Clowning “enables me to find room for my stupidity and that allows me to play more wildly. It gives me permission to align my intelligence with my stupidity.” The Center helped out, introducing her to two of the region’s most experienced clowns, Dominique Serrand and Steven Epp.

The threesome collaborated on a Playwrights’ Center workshop of An Almanac for Farmers and Lovers in Mexico; Kate says Serrand and Epp helped her find “the most poetic, essential, and funny aspects of the play.” With their insight, she was able to strengthen the plays “comic truth … and to reinforce its ritualistic aspects.” She loved the high level of playfulness in the workshop.

Being in Minneapolis has allowed Kate to be “open and surprised about how theatre can be relevant.” It has enabled her “to get back to the roots of my motivation and to live in an art-affirming way.” Minneapolis, she believes, has “a very healthy audience—healthy and not jaded.”

“The longer I am here,” she says, “the more I feel like the Center staff know me, understand me, and are getting to know my voice in a deep and continued way. It’s not a fling. They are set up to have a long-term relationship with every playwright. It is a pleasure to be known and understood and aided.”

Harrison Rivers, a soft-spoken African American, is one of the 2015 recipients of the Many Voices Fellowship and has just received a McKnight Fellowship. When we interviewed him on November 4, 2014, he had barely unpacked but felt at home in the Twin Cities and at the Playwrights’ Center.

Harrison grew up in Manhattan, Kansas. As a kid he dabbled in the arts and continued his experimentation as an American Studies major at Kenyon College. After graduating he moved to San Francisco and, following his mother’s suggestion, began to write. His first play, Prophet’s Wife, was a “big messy play filled with spectacle and rich in themes.” On the basis of this opus he was admitted to graduate school at Columbia University.

There weren’t a lot of African Americans in his class, but Harrison found a copacetic multi-ethnic group of friends. One night they went to the Public Theatre to see Passing Strange; this exuberant musical about a young black man’s search for identity spoke directly to Harrison. He discovered that there was an audience who wanted to hear stories about middle-class black people that he could tell.

After Columbia Harrison remained in New York. He heard about the Playwrights’ Center while doing a project at New Dramatists. He was tempted by the Many Voices Fellowship but reluctant to leave New York. He wasn’t sure about returning to his Midwestern roots; he was afraid that the Midwest represented professional isolation.

But after nine years in New York he was ready to take a chance. A phone call from Jeremy Cohen helped him decide to accept the Fellowship.

Harrison finds that it is good for his work to be in a quieter place. He likes it that the Center is an “unconstructed place“ that flexibly tailors its assistance to individual need. It is great that there is a physical space where he can be with people “willing to enter into my bubble.” Christina Ham, the Many Voices Coordinator, has become his mentor, his dramaturg, and his ideal reader.

For Harrison, a recent Center workshop of And All the Dead Lie Down is the best thing to come out of his Fellowship so far. Both director Faye Price and Christina Ham helped him find larger possibilities in what Harrison had seen as a small personal story. He is happy that the Many Voices Fellowship has given him the freedom to work at whatever ideas excite him. In addition to revising And All the Dead Lie Down, Harrison is working on the books for three different musicals, each with a different set of collaborators.

Harrison is optimistic about how the fellowships and the relationships he is building at the Center will affect his future. He has found a new professional network and Harrison is confident that “his name is being spoken in different rooms” now.

Conclusion

The young students who naïvely began the Center did not know that they were creating an institution, nor did they have a clear vision of what it might become. But from their creative energies, an institution evolved. Polly Carl, the former producing artistic director of the Playwrights’ Center and director of HowlRound and creative director of ArtsEmerson, observes that “there aren’t too many writers who have had success in the theatre who haven’t been there (at the Playwrights’ Center) at some point in their careers. …That said, its a challenge moving forward. I think what is required is how to look at the way the theater is evolving aesthetically and culturally and hold its relevance amidst tumultuous change—in a landscape where politics, social justice, and art can no longer be siloed from each other.”

The young students who naïvely began the Center did not know that they were creating an institution, nor did they have a clear vision of what it might become.

The Midwestern location, far from being a barrier to the evolution of the Center, has been a strength. Coming to Minneapolis has provided fellowship recipients with a new community, both personal and professional, in which to develop their skills. The area has served each playwright differently, but many of them have found that the Twin Cities are a good place from which to nurture a career.

While fellowship recipients expressed appreciation for funds that allowed them to practice their craft, the real value of the award is that it serves as validation and an encouragement. The Center has been an important source of money and personal support for scores of playwrights whose images now adorn the “Affiliated Playwrights” page on the Center website. Outside acknowledgment provides an incentive to keep at it and not to take up that abandoned accounting career.

The Center’s focus on the development of the writer rather than a specific play is its greatest strength. Since there is no production deadline or obligation to finish a specific play, the playwright is free to experiment and follow her or his creative impulses wherever they may lead. As a corollary, the Center is successful in meeting the needs of the individuals who come its way, whether that need is a connection in the Native American community, a talented mentor, or a group of clowns.

The Playwrights’ Center is positioned as part of a network of organizations across the country that provides different types of support to playwrights enabling them to thrive. As Idris Goodwin pointed out, “there are lots of excellent playwrights developing work right now.” The existence of the Playwrights’ Center and places like it inspire and promote that abundance.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Paul Bunyon, Barbara?