Smaller cities in the region tend to have a single city theatre, or two, where minorities are numerous. In Cluj’s case—the second-largest city in the country—there is both a Romanian and a Hungarian state theatre (and two opera houses). Despite their long-standing traditions and ample budgets, neither were able to respond to the ways in which the city had grown and changed after the second millennium. While the independent artists were searching for new aesthetics and more contemporary topics that spoke to younger audiences, the state theatres remained busy smoothing the careers of visionary directors.

In Cluj, a city ceaselessly battling with Bucharest when it comes to culture, artistic directors have chosen to dispose of the seemingly provincial idea of theatre for the people in exchange for productions made for the elite. But in this quest for higher art, big theatre institutions lost connection with the younger and less privileged audiences, and dismissed the very different aesthetics and politics of colleagues working in the independent field. This, from my experience and based on the research of fellow Romanian theatre writers, is generally true everywhere in the country: although state subsidy, in theory, allows for artists to experiment, take risks, and flourish, the generous amount given to state theatre institutions is usually spent on maintaining the artistic status quo.

But in this quest for higher art, big theatre institutions (…) dismissed the very different aesthetics and politics of colleagues working in the independent field.

As a citizen who grew up with the local state theatres but came into adulthood together with the local independent scene and by entering the international professional circuits, I developed a love-hate relationship with the big theatre institutions of the city. My first-ever job in theatre was playing the violin at sixteen years old in a performance by the Romanian National Theatre of Cluj, while during my bachelor’s degree I spent long hours volunteering for various performances at the Hungarian State Theatre of Cluj. I fell in love with and decided to pursue a career in theatre because of these experiences. When I entered the dramaturgy class in the Faculty of Theatre and Television of the Babeș–Bolyai University in 2009, I hoped at some point I would work in one of these institutions. But by the time I graduated, I was disappointed to realize the local state theatres had not grown with me. So I signed up for a master’s degree in theatre studies in Budapest, while simultaneously starting to carve out my career as a freelance artist.

In the years I spent both in the Hungarian capital and back at home, I survived with the help of a diverse set of skills that allowed me to work on a range of things in and out of the theatre profession. Apart from participating as a theatremaker, dramaturg, director’s assistant, and musician in various productions, I also wrote reviews and essays, translated texts and interpreted post-show talks, organized festivals and tended to international guests, spoke in panels and moderated discussions, and held seminars and workshops. I have grown to love the impossibility of defining a sole role for myself but, more importantly, I have come to realize the ambiguity of my work has suited my artistic purposes and helped me sustain a life and career as a freelancer in independent art.

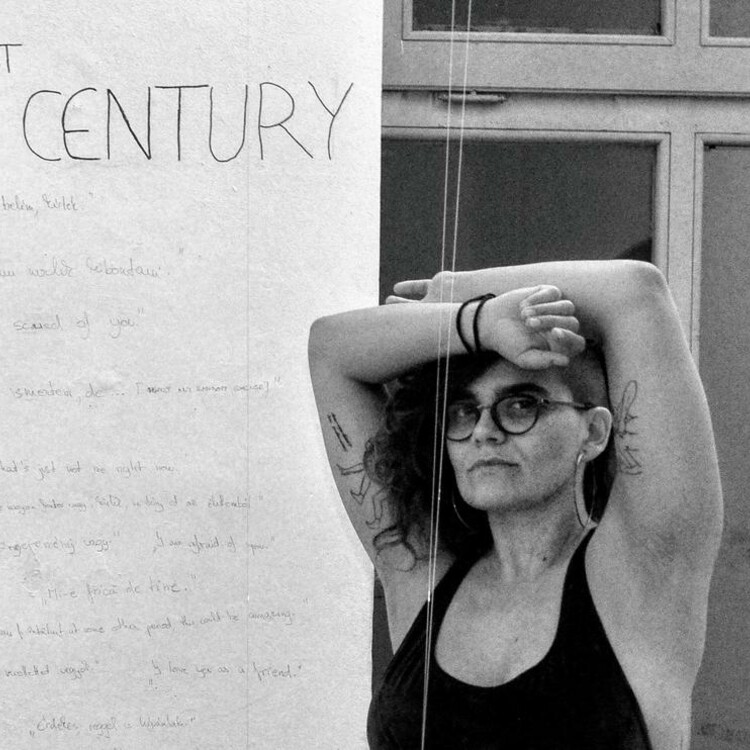

Like many others, I am lucky to have found in myself the will and appetite to fill in some of the void left by the opaque world of big theatre institutions, and to work until burnout to learn to create art that is more accessible and radical, friendlier and braver. Being an independent theatremaker in Cluj means creating a parallel reality where artists and audiences matter. It’s about working part-time at jobs outside of the profession. Not having health insurance, nor being able to put money away. Always going back to the question “Why am I doing it?”—a bit more often than is healthy—and to answer it authentically. It’s about learning new skills, never stopping studying, finding other ways to make something work.

It’s about becoming enraged and working to prove the world wrong. Wanting to believe fully in what you are doing.

Being an independent theatremaker means being dependent on the modest grants you have to apply for every half a year or so, paying the same rent as someone working in IT while earning half as much money, forgetting about all these things when you go into rehearsal. It’s about finding power in the closeness of the spectators in the under-heated black box you perform in, finding an infinite amount of joy in the playfulness that the performative present tense allows for, and finding a community in the people you collaborate with and in the audience you perform for. It’s about becoming enraged and working to prove the world wrong. Wanting to believe fully in what you are doing. And being silly, experimenting and failing, learning hard, opening up, and being forgiven.

To be an independent theatremaker in Cluj can also mean failing and then ceasing to exist, as faults—whether they are ours or the system’s—can be fatal. This is why the city’s independent scene feels as if it has reached its own untimely peak: the handful of tiny places mentioned above are struggling to engage the ever-growing number of younger professionals and are forced either to mindlessly over-produce or to stop their activities temporarily or definitively. Independent theatremakers have to constantly reinvent themselves to be able to compete for a life in the sector outside of the big institutions, and some of the more radical reinventions result in leaving the profession behind. To be independent means always considering this possibility, being prepared to give up, to resign, to let go. To say to one another: it has not happened yet, but anytime, who knows.

I have not yet given up entirely, although I am also constantly in search of non-theatre-related projects to help complement my earnings from the artistic ones. I have also not yet given up entirely on the state theatres, although mostly, when I go, I sit in boredom and sadness in the auditorium, fantasizing about a better theatre and a better performance, wondering, Were the performances I watched and loved here at fourteen years old any good? Is it possible I have changed while the institutions have stayed the same? Or is this artistic stagnation a new phenomenon, born approximately at the same time as the independent scene?

I will never know for sure. Change is a tricky thing, especially when one stays in one place for a long time. I have had the privilege of leaving my hometown and then returning, by choice. Accepting my hometown as my new home allowed me to form a stronger bond with it. But I have to ask myself: How will I be able to keep this relationship alive if this time I plan to stay? I have found my community, the people I want to work and learn with, and I also have found plenty of things to do. But the structure in which I am able to work is fading constantly. I am an independent theatremaker in Cluj, and the next time we meet I hope I can say this: I have not had to let go yet, and I don’t want it to happen, so fingers crossed.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here