How You Make/What You Make with Kirk Lynn of The Rude Mechanicals

From the Ground Up Episode #15

“The great experiment of Ensemble-based work, and those companies who are truly attuned to it, continue to experiment not just in what gets made, but how it’s made.” – Kirk Lynn

Kirk Lynn and the Rude Mechanicals exemplify the expression, “know thyself.” This company has weathered several transitions personally and professionally. Currently, with a shift from a long time rehearsal/performance/office space this company is starting to experiment with how they make what they make proving that ensemble-based work depends greatly on the individual’s dedication to the company.

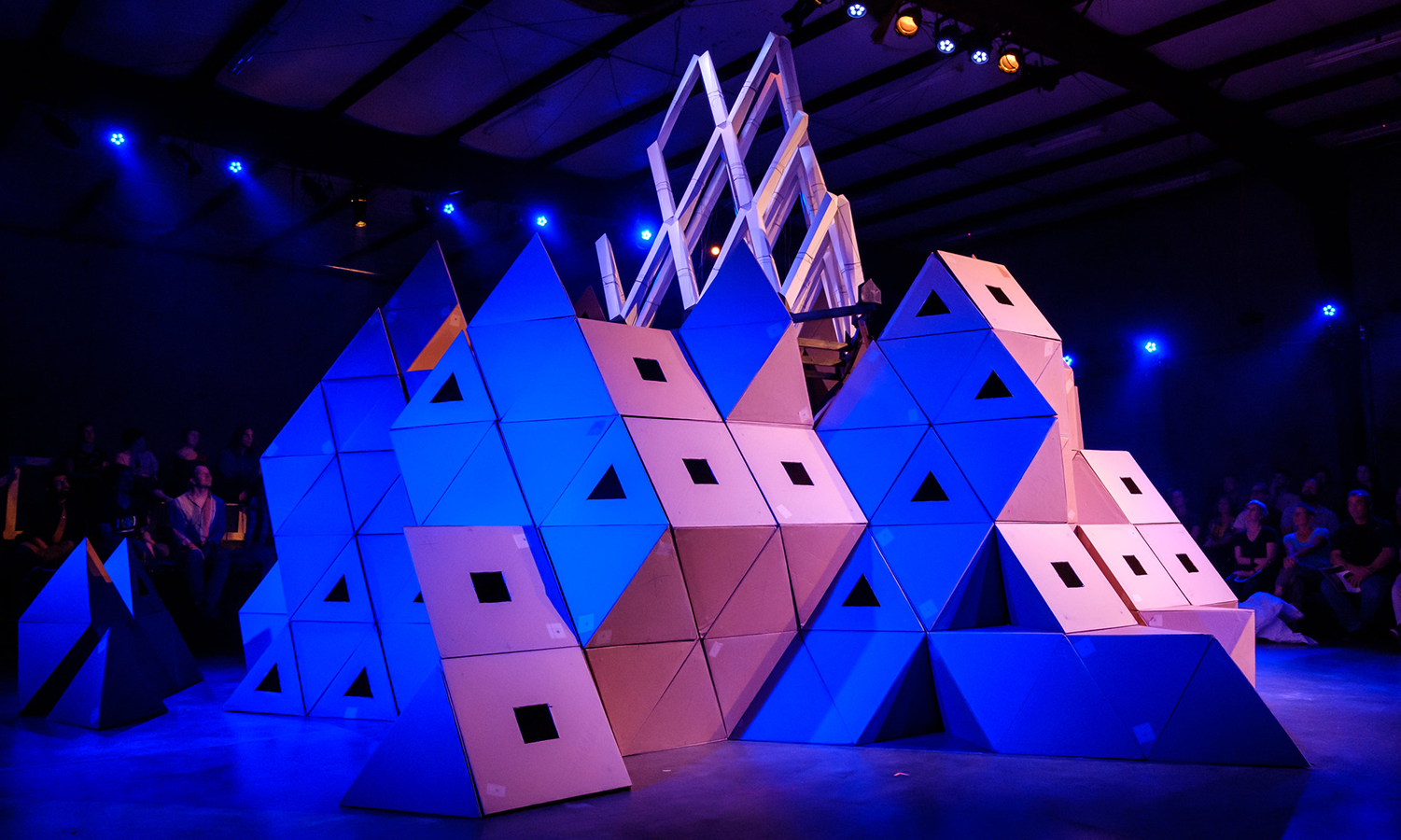

Not Every Mountain. Photo by Bret Brookshire.

Jeffrey Mosser: From The Ground Up is supported by HowlRound, a free and open platform for theatre makers worldwide. It's available on iTunes, Google Play, and howlround.com.

Dear artists. This podcast is the one that I've been waiting to share with you which is why I probably made it the last in this season. If you listened to my live TCG podcast from Miami you probably already heard me say some variation of this, but the reason why I've become a champion for ensemble based work is because I was able to observe several ensemble based theatre companies. The Rude Mechanicals of Austin, Texas being one of them. In fact, when I started a company in Boston, Project: Project Theater Ensemble, it was because this company had so inspired me by their process and their dedication to ensemble as an interrogation of the how and why we make theatre as well as the products that we could create as an ensemble.

Today, my guest Kirk Lynn, is one of the five co-producing artistic directors in the company. The Rudes wrote a play called The Method Gun which we refer to quite frequently within this episode. The play is so wrapped around ritual. Rituals we have in theatre, and in life. Because the parallels between these two things are so close in this play, it really shaped how I think about the work I want to make. And, because the play broke the fourth wall, and somehow still maintained characters' façade, I found myself captivated.

For over 10 years now The Method Gun has been a touchstone for me, and I could talk forever about it. So, please, next time we're in the same room together, and you don't know what to say, ask me why this play was so influential.

Kirk Lynn, in addition to being a Rude Mechanical, is a novelist and the head of UT Austin's M.F.A. Playwriting program, and a huge inspiration to me. When I wave my wand, I hope he is my Prochorus. There are some references within this podcast just to get you up to speed. He refers to Thomas who is Thomas Graves, a co-fellow producing artistic director. We also talk about the Off Centre which was the company's longtime office, rehearsal, and performance space. They've since gotten another space called the Crash Box which is a development since this conversation happened. He also refers to multiple projects, one of which was called The Replacement Tapes. A play that is mailed to you with a cassette deck, and a set of headphones for a group of eight or so people to perform to one another. And, finally, he mentions the name Cromer which is a reference to David Cromer, a director in Chicago, and elsewhere.

Also, some things not to be surprised by when listening, one we are having breakfast in a restaurant. So, beware some of the baristas and the dishes and some loud adjacent tables. Two, The Rudes were presenting at the Pivot Arts Festival in Chicago with their play Not Every Mountain which if it tours to you, please do go check it out. And, three, Kirk made me promise that I would bring my daughter to breakfast, and while I tried to edit most of her babbling out, our effervescent parent energy is spilling forth into every pore of this conversation so you know she's there. You've been warned.

All right folks. With no further ado, here's my interview with Kirk Lynn on June 8th, 2018.

Oh yeah, daddy forgot a bib so we're doing great. That Prince onesie is going to last forever.

Kirk Lynn: Wasn't it his birthday yesterday? I think it was Prince's birthday yesterday.

Jeffrey: No.

Kirk: I think I only know because they released an album or something.

Jeffrey: Oh my gosh, I've been off the radar for so long. Yeah.

Kirk: They released an album of him rehearsing alone in a room. It's just him and a piano.

Jeffrey: Isn't there a whole bunch of material that they're going to release too?

Kirk: Yeah, yeah. They're slowing releasing the vault.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah. The vault, yeah.

Kirk: Did you see the video of him? It's the audio of his version of "Nothing Compares 2 U."

Jeffrey: Yes.

Kirk: And, then the video is him rehearsing.

Jeffrey: Yes. Oh god. It makes me cry.

Kirk: When Olive was tiny I would write with her in a sling, and I had to write with my left hand because she wanted to suck on the pinky of my right hand. So, I would sit there. And, she would sit there for forever. It was pretty great.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Yeah. Nana. Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: So, school's out already in Austin, and so like right before I came here I was just hanging out with Olive all day, and I'd be like I've got to write for a couple of hours. And, she'd sit there and read or do her own writing. She's working on her own novel.

Jeffrey: Nice. Yes. Yeah.

Kirk: Saying things at dinner like I just don't have enough time to work on my novel.

Jeffrey: [laughing] I was just talking about somebody what it's like to have writer parents. I was thinking about that. We had a couple friends visit who were in town who are like faculty at University of New Hampshire, and they're both writers. And, I'm like it must be amazing to have writer parents because then you're always...

Kirk: Your premise is that people make books, and people have things to say.

Jeffrey: Your framework is like yeah, I have to be, I'm working on something, or I'm thinking about something, or I'm writing about this topic.

Kirk: Yeah, I wonder if that's a good thing or bad thing?

Jeffrey: No, I didn't mean to put a value on it. I was just like how does that work? Because neither of my parents did anything like that really.

Kirk: My parents didn't either, although my mom read to us all the time. So, books were like huge deal in my life.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: I don't know. It's funny, this new guy, the guy who's the new head of the Michener Center for Writers talks about this moment in his childhood, and his parents were not educated very much, and he got very bookish, and there was a moment where he thought that all books had been written, and he met maybe it was high school. Anyway, at some point there was an event, and he met a writer. He didn't meet him personally, there's just like a writer out in public. And, it was like, oh goodness, books get written. Like you could do this as a job.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: What a wild idea.

Jeffrey: Wow, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: So, yeah, I think the opposite. Like Olive and Judah I don't think it's like a big deal. It's like people just make stuff.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: One of my favorite interactions with Olive we were lying in bed in the early morning, and she was telling me that she wanted to be a pop star, and she wanted to be very famous. But, I was telling Olive, I was like well you know, you could, sometimes she was talking about what it was like to be famous, that you have to be alone or something, something totally weird. I was like well, you could be like mom and I, and you could have a family, and have friends, and also just be a little bit famous. And, she was quiet for a while, and she was like no, I think I want to be really famous.

Jeffrey: I prefer to have full blown fame monster in my life. Yeah. How's Not Every Mountain going? Are you loading in, teching, and all that?

Kirk: We just, we did actually a run yesterday. It was too long.

Jeffrey: Oh yeah?

Kirk: It's good. I mean it's been a little weird in that I just showed up yesterday going I can't be away from my, or don't want to be away from my family that long.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: So, showing up, and then trying to get into the groove of the room and everything.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: And, seeing what they're doing, and trying to be good company member, and trying to pull my load after I've been gone for a few days.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: So, it's good. We had a nice draft of a show where we felt like we had proof of concept, and now we start taking it back apart and change a bunch.

Waiter: Ready to order? Or, should I give you a couple minutes?

Kirk: I mean it's an interesting time to be here as a Rude Mechanical, and that sense of ensemble I think is changing for us over the last year.

Waiter: Uh-huh.

Kirk: I mean sometimes the threads of all these bits of conversation have, I think there's been a real interesting interaction of time, and one of the images we talk about is that when we started out we were really close, and on these, our trajectories were off by like 1% of like who wants to have a family and when, and who wants to make x amount of money, or wants to have a car.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Et cetera, et cetera. And, then as time goes on that 1% variance in two lines, like as an angle, you grow further and further apart. Then after 21 years, while there's still a great deal of love and affection, just where you are in your life is far apart. Which is not a bad, I mean I think in a lot of ways the Rude Mechs are more aligned than ever before, and yet able to recognize like wow, we lead really different lives. I mean, we're having a hard time probably post Method Gun having a hard time just finding the, you know if it takes us two years to make a piece, finding the time for all of us to sit in a room together and just do the work. I mean even things as simple as it's in a sort of almost Gretchen Rubin way of just looking at my life and figuring out what makes me happy and what makes me sad. That I don't like rehearsing at night. I like rehearsing during the day, or afternoon. The day is great, and then at night I can go home to my, I can be there for dinner, and be a good partner, and be a good... You know, be with my family, not make my wife do all the fucking cooking and cleaning, and washing the kids, putting them to bed. And, then actually spend time with my wife.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: That's an ideal life for me.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, just like that. And, then how many performers can rehearse during the day and not at night.

Jeffrey: Right.

Kirk: It's like small. I mean it's, they're issues that seem small, but in fact have this big impact on how we make it work. So, in the last, I would say, year and a half or two years we've been sort of saying almost like make work however you want to make work, and whatever size groups. So, in some ways Not Every Mountain was like Thomas and I really wanted to do this work, and it was a priority to us to rehearse during the day, and that the performers would be dancers which is not a strength of most of the Rude Mechs company members.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: And, so we largely cast outside the company. Although, not entirely. We work during the day. We did it on a shoestring. But, we still call it a Rude Mechs piece even though it wasn't all five artistic directors.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, Lana and Peter are making this piece Grageriart, it's based on like, I mean I would say it's sort of critiquing lifestyle design, and IKEA catalogs.

Jeffrey: Oh my gosh, yeah.

Kirk: It's really beautiful, and fun, and funny.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: But, for the most part they make it in their living room when they do presentations. I have a solo show that's going to be at Under the Radar.

Jeffrey: Was it at Fusebox, too?

Kirk: Yeah, it was at Fusebox.

Jeffrey: Oh, but that was going on... That's awesome. That's great.

Kirk: But, it's still a Rude Mechs piece. At least we're just saying everything's just a Rude Mechs piece.

Jeffrey: Sure, sure.

Kirk: But, I think that we are also conscious of like what does this mean for the company to let ensemble be redefined in this way. And, I don't know that we have answer for that yet, other than we don't want to lose each other, we don't want to stop making work, and we want things to fit into our life.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: I mean the idea was that we would then have moments where we came back together and said this is what I've been doing, this is what you've been doing, how do these things talk to each other? How does the work intersect? We also had this scheme in our minds that you could make work in a way that you could, you know, if the Guthrie is going to bring us in, and they have enough money to bring all five pieces, then they bring all those five pieces. But, if there's a little college in Vermont that only can bring the solo show, they can just bring the solo show.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: That the pieces intersect in these different sizes and scales.

Jeffrey: Well, to me it sounds like it's not just then the company being an ensemble of individual people, but a company being an ensemble of the aesthetics, the choices, the sensibility I think is the most, everyone has a sensibility, and it's a Rude Mechs show even though it's two of us are in, one of us is in it.

Kirk: And, there is a sense of like oh, well this is a well-made play that's scripted, it's around the kitchen sink. Like that's not a Rude Mechs show even if it's by Rude Mechanical because that doesn't fit that sensibility.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, I think there still is a longing, I don't think any of use imagine that we'll never work in the same way again where we sit all of us in a room and debate, and decide, and try things. But, just opening up. If it's harder to do that let's just work in a multitude of ways, and experiment with how we work.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Which to me, in some ways, is the spirit of devising which is one of the ways I teach it is to talk about just a consciousness on how you make, rather than just what you make.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So that you're thinking about well, if these are my inputs then my product will be different because we're working in small groups, or we're working in big groups, or we're inviting in new people. It's equally important for the Rude Mechs now I think we're at a phase I think where we all feel strong enough and responsive to the times to also diversify our company.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: And, that that's going to change us in certain ways. And, that that doesn't make anything less Rude Mechy.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: To sort of say.

Jeffrey: Yeah, because right now, if I remember right, the last time I looked at your website you have thirty-some, thirty-three, thirty-four ensemble members, I think.

Kirk: That sounds about right. Yeah.

Jeffrey: And, the...

Kirk: Company members.

Jeffrey: Company members. However. Do you bring people on who already sort of have that sensibility, or some folks who resonate with some part of it already?

Kirk: These days we are saying that if you work on three shows, you're a company member. I think that's the new. And, then usually by the time you've worked on three shows that you wouldn't be back for your third show if you're not in that spirit. And, then also, I think at any moment anybody in the company that exists can say oh, Susie's really badass, and essentially nominate them for company membership.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: We want to acknowledge their contribution.

Jeffrey: Like decision making for content, or like hey, I'd like to do a two person show and go in this direction with it.

Kirk: Yeah, so we still, you know we just did it not too long ago. We go on retreat, the five artistic directors, and we sit around and talk through, I mean we talk some business, but we also talk a lot of like what's happening in our lives, what we're reading, what we're moved by, what we're interested in making. And, sort of make plans that way collectively. And, it's become so casual. I mean casual may not be the right word. I think it's consensus based decision making is so in our culture.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: That there's not a moment of like okay let's vote. I mean the senates are supposed to say is are there any outstanding concerns. And, when there are no outstanding concerns, you have consensus.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: The podcast will never know how what an astounding feat of fatherhood this is to watch you talk to me, feed your baby, and feed yourself. Possibly feed yourself.

Jeffrey: Right, well I haven't eaten anything yet. That hasn't been hers.

Kirk: It's a potential though. It's a clear potential.

Jeffrey: Right, right.

Kirk: It's on the board as a possibility.

Jeffrey: Thank you.

Kirk: So, yes, we still get together and have these conversations. And, it's really interesting now also being professor and watching UT which is hierarchical. I mean, it's set up as there's a chair, and there's an associate professor, there's an assistant professor, there's a lecturer. The power of collective decision making seems all so amazing to me know. There's a kind of efficiency where, there's these different kind of efficiencies where at University of Texas I think there's a sense, and in a super hierarchical structure they're like oh, the chair said this is the new policy, you all put it in your syllabuses, and implement it. But, because there's not consensus, that the implementation is super uneven, and it's unclear whether the chair can make anybody do anything. But, where you have consensus there's a lot more conversation on the front end of what should be our new policy, how are we going to do it.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: But, then once we reach consensus because everybody's onboard, the implementation is instantaneous and efficient.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, it's like where do you want your, I think there's a feeling at UT of like oh, we don't want to talk that much, we just want clear leadership quote, unquote.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: But, in a leaderless organization there's like a little bit better vision and direction because everybody has consensus. Which is all to say we have all those meetings, and we sit and talk, and I don't, it's hard to pinpoint a moment where we decide because it's much more, it's consensus. It's when the group, in a weird way, it's like the lack of conversation in some ways implies consent because we're all agreed. We don't need to speak about it anymore.

Jeffrey: That's interesting because it sort of is, I guess that's diplomacy in general though, and that's not necessarily... But, I mean it is something, diplomacy and egalitarianess of like we all need to somehow win, or we all need to find, not win. We need to find...

Kirk: Yeah, what's the common ground in which we all meet in this?

Jeffrey: Common ground.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, we can all see a way forward with our own actions. And, it's interesting how it intersects with art. I mean one of the things that has been nice about working with Thomas is I think both Thomas and I are less discussion based in our art making, that we don't want to spend a lot of time talking about what the show is, we just want to try it. And, that sometimes the five of us, the full collective of artistic directors talk a lot. We sit around a table, we make a lot of outlines. And, maybe it's a function too of having kids and family, and time feeling more precious of I'm less interested in talking, and just want to make drafts.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And things. And, I teach this and I practice it, I believe that the work in a lot of ways discusses itself. If you put up a draft and look at it, the work sort of tells you. You don't need to sit around and talk about what might happen if we do this. The work speaks. The work shows you. I think in the ensembles I think action versus discussion is a real, is an interesting balance to try and strike.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: You don't want people to feel shutout or silenced, and yet you can spend all your time, you could never make anything because everybody wants to share ideas.

Jeffrey: I always say show me, don't tell me. Can we just try it. We'll just do it.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: I think the logic is there for me. You don't need to prove yourself any further. Just show it. Let's just do it.

Kirk: And, I think of if one of the premises of being in the performing arts is that we make live things, and the liveness matters. I think that intersects with that practice about are we going to discuss, or are we going to do it.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Because the liveness with show us how it works, and if it works.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Whereas the theory... And, then I think this is in my mind to say because one of your interests is in funding. I mean there's an interesting divide of who gets paid what by the company, and then who lives on what.

Jeffrey: Totally.

Kirk: And, who needs what. I think both having a family, and then taste wise I want more money, so I have this full-time job at the University of Texas. Where I think there are other people who are like well, I actually want to have more, my time is more important.

Jeffrey: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Kirk: So, I don't want a full-time job, and I'll take x from the company. I mean, I think most of them not that they wouldn't take more money, especially for their art, but they don't want to teach, or they don't want to do that other extra, they don't want extra income. They want to get paid for their art, and focus on their art.

Jeffrey: Well, you rehearse if you're not getting paid for it.

Kirk: Yeah. Absolutely. I mean I think Not Every Mountain was made with, yes, I mean there's a number of projects that we make without funding. I mean now the company, we're not a very big company. Our budget's probably about 350,000 to half a million depending on if we're touring. Probably more than 350, 000 these days. So, it's not like we have zero in the bank.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, if there's a project. I mean, Not Every Mountain really was this way. I think we might have had 10,000 from the NEA which is a good pot of money. But, we made a full production out of it. And, we mostly paid actors. But, there are other projects, our Fixing Shakespeare series, our, there's a couple, The Replacement Tapes, and the Christmas Carol Karaoke, things we want to mess around with, has no outside funding and we just get a little money from the Rude Mech's bank account, we pay the actors, and then we just try things, and then hopefully we pay it back from ticket sales or whatever.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: But, we rehearse. So, I'm trying to speak in real talk because the Cold Record is a solo show that I made that I just sat in a room alone with tape recorder and made.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, I'm working without any money. And, then Alex from the company directed it, and I got her a little money from my research funding at UT.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: So, like there's money. And, UT is paying me quite handsomely so it's not like I'm working in a room without electricity or heat. It's like I have the time and the resources partly through my teaching at a research university.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. How have things changed since the loss of the Off Centre? And, moving out of the space that you had as a home for a while?

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Maybe too soon? Too soon?

Kirk: No, no, no. In fact, we're just past the one year anniversary. My belief is that Method Gun we could make 10 foot steel poles, and drop them in the ceiling, and they could swing around, and we could break all the... There was a great night where Lana was handing Thomas a highball glass, and a steel pendulum knocked it out of his hand and it shattered against the wall. And, we were like that's good, let's recreate that. And, we spent the next two hours destroying all the glassware in the Off Centre, and really butchering Lana's hand.

Jeffrey: Oh no!

Kirk: There was night when we wanted to start El Paraiso by lighting an arrow on fire and shooting it at a sign that was made out of flash paper so that it would explode.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, we spent all night dipping arrows in kerosene, and shooting them across our theatre, and realizing that archery was a real skill that we didn't have. And, then Tesla, we could show off a Tesla coil. I think all these ways in which we had a place for a real laboratory, we don't have that anymore.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, we can get space in UT. The Guthrie is letting us finish Not Every Mountain up there, but we can't set their place on fire. We can set any of those places on fire. We can't screw into the floor. I think the most immediate impact right now is that all the work that's coming out of Grageriart, Cold Record, all the work that's been made post the loss of the Off Centre is in some ways without production values. It's just this is work that you can make. It's very human. Replacement Tapes were a response to the notion that we wouldn't have a home.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Making theatre without a theatre. And, then I think over time it will be interesting to see how it impacts our style because we, I don't know that we know what our style is, but you can certainly look at a kind of physical stupidity with the pendulums, and with shooting off the Tesla coil in the middle of the theatre, and not having a space where we can do that. It's going to change things.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Kirk: And, also just like, I mean we have rehearsal space right now. It doesn't feel the same. It's not as clubhousey. It's much more corporate. It's at the Austin American-Statesman. So, if we leave a door open, if somebody brings a dog in, parking is weird, so it doesn't feel like a clubhouse any more.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: I mean it used to real be the center in Austin where you could tell students all the time oh, I think the Off Centre is free. You can have this room. Or, we just gave away the space. We met there more often because it was our clubhouse. I think some of the artistic directorship right now doesn't really like the space that we're in because it's fluorescent lights, and little cubicles.

Jeffrey: Sure.

Kirk: Yeah, it's changed things. I mean our plan now is to still, I think we're still aiming to get a space.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, when we get a space we'll hopefully turn it back into a clubhouse that we can set on fire.

Jeffrey: Yeah, right, right. Yeah, I will say that feels like a defining thing that use of objects in the room as what they are, but also in an extraordinary way, is really fantastic. Yeah, like swinging poles, and things starting on fine.

Kirk: Are you going to see Mountain?

Jeffrey: Yeah, tomorrow night.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: Mountain is just cardboard boxes. There was just a New York Times article that was like singing the praises of cardboard. It was talking about all these big corporations like Nintendo, and Google.

Jeffrey: Oh, yeah! Yes.

Kirk: And, a lot of their big innovations are them making shit out of cardboard.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, I was like, I mean Not Every Mountain is, I mean it's a lot of Thomas's brain making these beautiful, magnetized tetrahedron pendulums. But, the manipulation of those simple objects.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. Thank you.

Kirk: To make this beautiful mountain, hopefully beautiful mountain.

Jeffrey: But, yeah, it's the everydayness being changed into a mundane, even though arrows and steel poles are not necessarily mundane everyday. But, like transformed into like a metaphor, or is really the style and the aesthetic that I love about y'all.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: I think that's great.

Kirk: I think there is a sense of we want to, I don't know how I would put language around it, but we want to make a rupture and invite beauty into the room. And, the tools that we have to do it are the shit...

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: We don't have another way to do it except by forks, and knives, and hammers, and the dumb shit that we have.

Jeffrey: Right, right.

Kirk: But, there is a desire to make something really beautiful. The Mountain feels nice in that regard. And, there's an interesting, a different kind of sustainability, but then Thomas was really interested in making set that it's all put together. Look, I'll show you some pictures.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: One of my favorite moments was when we put it together. It's all binder clips and cardboard. It packs flat and then we can ship it anywhere for super cheap.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Thomas is super excited that he's got it so the set, it fills up a theatre with a mountain, packs down so small that he can fit everybody's bicycles into the van that's delivering a set to the Guthrie so that everybody can bring their bicycle.

Jeffrey: That's so cool.

Kirk: That's so geeky and fun. The most expensive part about this set is the rare-earth magnets that keep it all together.

Jeffrey: Oh.

Kirk: Everything else is like a paper product.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. I remember you telling me back in the day that in the early days you were sort of like you were creating the titles of plays, and then you were saying hey, we've got three shows, but you hadn't written the shows yet.

Kirk: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey: How did that change? Or, the choice of shows, or the generation of shows, change with the company? Like did people want more... Was there a desire for more stability? Or, different ideas? Or, some other generation means?

Kirk: I wonder how much it's changed. I still think there's this notion, I think both Stop Hitting Yourself and Field Guide which had these beautiful commissions from Lincoln Center, LCT3, and Field Guide from Yale Rep. And, we basically sort of pitched a title and a concept, but the way we make work is to go off in a room and devise for two years. And, so the show doesn't exist. And, so as we start working, we figure out what the show is, and it meets the title. We have no idea what we're doing. We have this sort of rough notion that we want to really make a play that would tell people how to live. We thought that was a fine idea.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: At some point we met the brothers, like the show became this other thing. Or, it didn't become another thing. It didn't exist. It was just a... So, I think we still, I mean essentially think about how it intersects with funding models. To get all five people in a room, plus whatever the cast, and designers, and all of that we need funding.

Jeffrey: Right.

Kirk: And, those things usually we pitch first without knowing what they are. It's not unlike publishing maybe, if you get an advance. If you get a two book deal, your next book doesn't exist.

Jeffrey: There's a trust in the content.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Or a trust in the method.

Kirk: In the process.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: But, so I mean I guess there's different kind of projects. Some of them like Cold Record, or Replacement Tapes, there's an actual idea for a project and let's just do it, figure out how it gets done.

Jeffrey: Uh huh.

Kirk: And, it's not funded until it gets finished. And, then there are projects commissioned. So, I think there's still, I mean it depends on what the goal is, how we're doing it.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: We still sort of pitch ideas, and then fill in what those ideas are later. We earnestly aim for making a show about advice and how you tell people how to live, and why literature wants to do that, or what part of literature wants to do that. And, then by following that road, and spending two years working on that, you find yourself in another place. That's really a, you know, Method Gun was title, and we sort of had the concept that there was a really dangerous acting exercise. And, I think that was all we knew. And, then we got to this notion of thinking about truth and beauty and what the relationship of the two is. But, then the character Stella Burden arrived later. And, then the disappearance of Stella Burden arrived even later than that.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: It just sort of grew organically.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Sort of what you need. Whatever you need to create the myth of this method kind of thing.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: I know we talked to Charlotte Canning, and one of things that's at the University of Texas, and I think she led us in this strange way of talking about how great directors have these relationships with great writers, and we thought a lot about it. I think that's how the character of Stella Burden really rose up.

Jeffrey: What were some of the growing pains between in the years? Where did you feel like oh, you know, we...

Kirk: They're all still happening. I mean it's good to be 21 years-old, and to be established, and to feel secure, and all sort of feel awkward 12 year-olds at the same time.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: I mean I think we struggle a lot with being in a collective, like being in a marriage, being in a family, being in the ongoing maintenance of our relationship is always difficult and fraught. We love each other very much. Uncertain of one another's motives. None of those things means we don't love each other or want to be with each other all the time or are our favorite collaborators, but just the daily interactions are fraught. I feel, these days, even seven years into having a daughter feel anxious all the time about balancing my family and work life is complicated for me, and complicated for me and my wife, and then complicated for me and the Rude Mechs. Just this week, being like well, I can't come that whole time so I'm going to come in on Thursday. I feel, there's a part of me that walks into the room feeling guilty for not being there. And, that's not necessarily good for the room. And, then finding the way to work together. Hoping that everybody else does well. He's doing what he can, and we're doing what we can.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: I mean the growing pains were made sort of emotional maintenance.

Jeffrey: Were there like hurdles that you were like oh, if we can only get this then we'll be at this rung of the ladder. If we can only get this.

Kirk: I would say this, I think now there's a momentary, what feels like wisdom, to feel like oh, we take joy in the work, and that's the most important thing and all the other stuff who cares. At other times there's feeling of like oh, we need more money, we need a space, if we had space, if we only had more time, time is a big one. I don't know that I believe any of those right now.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: You know, us getting health insurance for everybody was a really big deal.

Jeffrey: Sure.

Kirk: That felt like a huge thing.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, now I'm 46, people are getting older in the sense that we actually need health insurance. We never had a catastrophic event when we were younger, although we had times when we were like, there had been moments when being in a collective where we pooled all of our money to buy somebody a car, or we pooled all of our money to help out with bills, with medical bills or whatever.

Jeffrey: Wow, yeah.

Kirk: Those times seemed long ago now. It mattered to us. I remember just milestones of like the first time we got a Rockefeller, which is a MAP grant. We made photocopies of the check, and so everybody could have a copy of the check and like play this game where we'd drop it and we'd be like oh no, don't drop my Rockefeller check. Will you help me pick it up? It's so huge. When what was our more outreach sort of sided program and now Off Center Teens. Like I felt the moment where we matured where we started thing consciously about not just making our art, but giving back to the community in some way.

There are moments when it feels like oh, nobody's doing our work, or we're not a part of the national conversation. We really have to struggle to get seen, and to be back in the nation conversation which probably seems ludicrous to other people who are like I've never been in American theatre. And, then funding always feels like how do we get into this cycle, and who's getting funded now, and how do we develop more. And, I think right now there is a big consciousness around how do we diversify our company. Collectives are very insular in a lot of ways. There's a lot of hidden I would say bias. I mean some of the things we were talking about are like how do you know it's a Rude Mechs piece, or that's a Rude Mechs person? A lot of those things are coded, and dismantling that, and finding ways that we can both dismantle our own bias and our own racism, and also make the organization look attractive and inviting to people who feel themselves outside of this insular world. And, if there's any feeling now of like oh we're really, I think when our company matures in that direction that'll be a new milestone.

Jeffrey: So, you had national recognition, but you're also, one of the things that I really love is you're super dedicated to Austin, and your home, and all of that. When did you start saying how do we look outside of our local bubble?

Kirk: I mean I think our founding was in the sense that there was a kind of work that wasn't being done in Austin. I mean I was writing in this very sort of absurd style, and Shawn had just come back from NYU and had all this influence of Deb Margolin and Karen Finley and Holly Hughes and the City Company of Richard Schechner and the Wooster Group, and making work in that spoke to and about Austin and the current situation already has this national feel of like, it's like when punk hits Iowa or whatever. It's like oh yeah, that music, the feelings that the music speaks to are already there, and the subculture can sort of coalesce around it. I think Austin was ripe at that age for the feeling of what it means to be in a collective, and to not feel alone, and to speak collectively, and to speak as an ensemble was there and that it could coalesce. And, now I would say it's almost like, now there's a really healthy, thriving sense in which the work in Austin is frequently devised, and frequently made by ensembles, and it feels great.

Kirk: But, I think so at first there was already a sort of a national consciousness just in the way we wanted to make work like other people in he nation were making work. Then we wanted to speak back to those people, and to those scenes, and to find a way to say that what's happening in Austin matters to the national conversation.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, I think maybe some of what you were saying at the beginning of our conversation that this work is valuable, and it's not seen enough that too often a sort of centralized, perhaps even efficient way of working, gets seen the most. I mean, I'm an author, I believe in the singularity and the beauty of the author's voice. I think magical things happen when you sit in a room alone and write slash pray. Whatever the fuck you're doing.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: And, I don't think scripts get written alone. There's all sorts of supportive, trusted readers, partners, ensembles, actual directors, the people who actually sit down and first read a script when it's ready to be read aloud. And, those people mostly get erased. So, I think a lot of work that is not credited is being ensemble based. It's in fact being supported by this large, and you could encourage people to have more fidelity toward the ensemble that lifts them up. It is in the, to the extent that there's some sort of hierarchy. I mean it's just easier for most foundations to fund individual writers than to fund communities. The writer is easier to be seen than the director, or the dramaturg in some ways.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: But, there are little, you know NEFA funds ensemble work in a nice way.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Or, things are changing I think.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Absolutely.

Kirk: I think there's a lot of political interest right now, but I absent that I think a lot of foundations were getting interested in this notion of how do I fund communities instead of big regional theatres.

Jeffrey: Uh-huh.

Kirk: And, I think anywhere in the world you can look at. You could basically look at any regional theatre's artistic director salary and you could steal all that money from that person and you could fund 100 artists.

Jeffrey: Totally.

Kirk: It's ridiculous. And, I think that should be done more often.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Most people don't need that much money. The same could be said of a professor perhaps at a regional institution.

Jeffrey: I was going to say that I think I was listening to a podcast, and they were talking about interviewing Oskar Eustis and his idea at the Public was to their next capital campaign idea was to fund artists rather than spaces.

Kirk: That's a great idea.

Jeffrey: Et cetera.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: So, I think, yeah, stealing money from whomever, like however you acquire the money, putting that back into the artist. It's such a, I guess also in this interview it's Oskar Eustis is so overtly communist, or talks about that sort of shared wealth, or shared ability to make things that I find that really interesting. So, I don't know if I'm going anywhere with this. But, I find that his idea of like yeah, we should be making this. The artists are what are making the work the thing that we value. And, the artists are seeing things in our society that we need to be seeing.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Let's put the money into them instead of into infrastructure.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Yeah. So, how can we fund that time?

Kirk: Yes, and he already has infrastructure which is really nice.

Jeffrey: Yes.

Kirk: He has a bunch of spaces, and can use those spaces which doesn't mean that his vision and his dream is wrong. It's just that it's also a luxury to have that space.

Jeffrey: Totally, yeah.

Kirk: All those spaces. And, a luxury to get paid when he gets paid. And, then from that position it's easy to think about well let's get everybody paid.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: I mean, I feel that way. I make $100,000 or whatever at the University of Texas and then I can start saying oh, artists should always be paid.

Jeffrey: Do you think that we're getting close... I'm hearing more and more about theatres, about large regional theatres, that are sort of bringing in the smaller ensemble-based works, and there are secondary stages and spaces, like the Guthrie that you're going to where they're making an effort to bring in ensembles and make this like national known work more visible in their local regional space. I'm wondering, I don't know, do you have any take on that? Do you feel like that's, is it a trend? Is it something that we're going to be moving toward? Or, is it just a way for that wealth to be shared in some way?

Kirk: I mean, my gut reaction is this, that I think we're at a great age of playwriting. There's all these fantastic, there's so much great work being made, and almost all of it has the same flavor. It works the same way. And, then after a wonderful period that I would describe as maybe 20 years of like a lot of great, well-made plays, the differences are not that amazing. And, I do think with ensembles you think of somebody like Radiohole. They just taste it. Like it looks nothing, it looks and tastes nothing like a well-made play. So, the difference between any two well-made plays is infinitesimal. And, the difference between frankly any two Radiohole shows, but like Radiohole in a well-made play is vast.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, so I think that the sense that diners have become more aggressive in the kind of palates that they want to experience, I think that consumers of art want a wider palate. And, so ensembles I think can provide. I think formally you automatically because you're inviting three, four, five different minds to speak in a single voice, you get this richness and depth of flavor that you just don't get in a single authored script.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, I guess the short answer is I think it's smart of artistic directors and big regional theatres to think about how we offer a wider palate. How do we offer a palate is as ambitious as all the local restaurants that are near and surround us.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Is the fare that our cultural institution offering as challenging and diverse as what this coffee shop we're sitting in with its cayenne inspired coffee. You know, regional theatres have worked a lot like diners in some ways of oh, we do the standard bacon and eggs, and we do it really well. And, we do it over and over again, and now I think it feels great to look at ensembles. I'm sure, what other things are we not looking at? I think Philly seems like a town that has this dance theatre just falling out of its wazoo. How do we get more of that out in the world? I mean it seems like Pivot has brought us here. One of the things that they do is bring a different flavor into the Chicago theatre that's like okay, we've got storefront on lockdown, let's do some other stuff, too.

I mean do you have a sense that you're going to make devised work? Or, that you're going to do everything?

Jeffrey: I mean, I feel like where my heart is is in devised work. Like I really feel like my thrust, and my energy all goes into that. But, I've had my, when I was in Boston I was doing a little bit of both because I did start a company to do devised work, and then I was doing everything else, a new play kind of stuff.

Kirk: Yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey: So, my personal take has been to do a little bit of both. But, most of what I was doing in Boston was new plays regardless, like across the board new plays. At the same time, just now, I did my first old play. Not really, but I did Twelfth Night for my thesis project.

Kirk: Oh cool. Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Jeffrey: And, it was the first time that I've done Shakespeare.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: So, that was exciting. I feel like I have the tools to make something new out of something classic of some sense.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: And, I'm kind of interested in maybe looking at that right now. Like just exploding the text. Who says we have to honor this dead guy's text anymore, you know, kind of stuff.

Kirk: I would also argue in this like steady of the relationship of playing and writing, the notion that Shakespeare one of the reasons why he's so serviceable is because he's playable that it really is like music to be interpreted where I would argue the trend in a lot of well-made plays right now is not to offer, is to offer clarity and a point of view. Where Shakespeare's offering a much more complicated. The idea of a musician interpreting of like we can make Merchant say a lot of things. We can make Twelfth Night say a lot of things.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: Because he's purposefully written a text that's playable.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: The bad guys are good guys, the good guys are bad guys.

Jeffrey: Yeah. Well, Shakespeare is still like humanity, right? Like it's still speaks to humanity, and that's just like the point of view, what you want to say.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: New plays are so like we're speaking to an issue that hits the playwright's heart.

Kirk: Yeah, and we have clarity about that issue. We know, yeah.

Jeffrey: In attempt to get more national sort of visibility I think, have you ever had a non-Rude company do a Rude show?

Kirk: We have a couple times. Somebody did Lipstick Traces in Chicago I think. Pavement Group? It was a thousand years ago. They may not exist anymore. I still follow David Perez who's a standup comic now on Twitter. He's funny as shit. I think he was the artistic director of Pavement Group, and other than that I think it's just a couple times here and there. I think occasionally someone says can I do it, and we say sure. Cherrywood got done by a high school.

Jeffrey: Right. I wasn't sure if that was a Rude show, or if that was a you.

Kirk: Yeah, it's sort of, I mean it was a, you know it's uncharactered dialogue. It's just a list of dialogue. And, so I made it for the Rudes to like, so that trying to think about new ways to collaborate as a writer and an ensemble.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, so it sort of works as just a script you could send out, but oh and Cromer did it here in Chicago.

Jeffrey: It happened at Mary-Arrchie.

Kirk: Mary-Arrchie, yeah.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: Yeah, in short, yes. God, we had a conversation recently about, you know frequently in our shows we address one another by our names. We say that was a good scene, Tom. And, in Lipstick Traces they frequently say thank you, and then the actor's name. So, the actor's playing a character like Guy Debord, but at the end they say thank you, Robert. And, we had a big discussion about who to, what name should they use. Should they use the original actor's name, or should they use the name of the actual actor? I think we decided they should use the name of the actual actor.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Because that's the human.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, some of that's borrowed all the way back from talking about being influenced by the Performance Group doing Dionysus in '69, and really conflating that notion of like I am Dionysus, son of Zeus, my name is Thomas Graves, my mother was Margaret Graves. Like conflating the sort of personal and sacred in this way.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: But, yeah, I think we're totally open to it. I think usually we think like oh, once we stop touring, and we're not carrying it around, anybody can do it. But, we haven't also, I mean Lana is preparing the Lipstick Traces script for publication by 53rd State.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: And, she's actually doing this beautiful graphic novel. I think once some of our scripts sort of exist in the world, right now they just get emailed around. Like I have no idea, I heard Cromer did like teaching exercises from Cherrywood first, and I have no idea how he got the scripts.

Jeffrey: Oh, funny.

Kirk: And, then when they called me to ask for the rights, I didn't know that anybody had the script. I never sent out the script.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: So, somehow it got out. That's always really fun. Jamal from the Universals, when the days of LimeWire, told me this great story where he'd got on LimeWire and he was downloading something, and he saw that the Universals were on LimeWire, and he first thought was like fuck, somebody's stealing my shit. And, then his second thought was like we fucking made it.

Jeffrey: Someone's stealing our shit.

Kirk: Yeah, somebody's stealing our shit.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. I think that's what I was thinking about because I have a couple of plays by the, I have a Pig Iron collection of plays.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: And, I'm like oh, I wonder how often these get passed around. Or, how often they get done. I haven't really dug any research. But, 53rd State Press does that. And, I was like oh. But, an interesting way of like a source of income, and like a nationally known sort of way to like publication is a way to pass it around, and like scripts being passed around.

Kirk: I don't know which. I mean, you could be pretty stupid to do our plays. You have to want to build steel pendulums, or you have to want to have a Tesla coil.

Jeffrey: Tesla coil.

Kirk: A book review insert.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah.

Kirk: There's a great book. I don't know how to pronounce it. I think it's by Ontroerend Goed which is this Dutch company.

Jeffrey: Okay.

Kirk: I think they're Danish, Dutch.

Jeffrey: Okay.

Kirk: Europe has all these countries. We don't need to know each and every one of them.

Jeffrey: Right.

Kirk: But, I know the title of the book is All Work and No Plays and there's a collection of about nine of their play scripts, but I think they have the text from the scripts, but more importantly they have these detailed notes of how they devised it.

Jeffrey: Oh.

Kirk: I think what they're encouraging you to do is not just like quote our actors saying these things, but go through the process by which we made this play and come up with your own. I love that book. It's so great.

Jeffrey: That's great. That's great.

Kirk: And, they had a piece I saw in New York called, yeah it was Once and For All Shut Up and We're Going to Tell You What We Think, or something like that. And, it was fifteen Dutch 15 year-olds doing this beautiful movement sequence, but also telling adults like this is what it's like to be 15. At the center of this, this beautiful monologue about like you'll tell me not to drink too much, or smoke too much, or stay out too late, but I have to do it for myself. I have to experience it myself.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: That's a funny baby.

Jeffrey: I know, right. Can I run us through the lightning round and we can put a pin in this animal?

Kirk: Yeah, yeah let's do it.

Jeffrey: What's your favorite salutation?

Kirk: Howdy. Like that?

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Yeah, I say howdy all the time. I think people think that it's ironic because I'm from Texas, but I say howdy because my dad says howdy because that's how I was raised.

Jeffrey: That's how it happens, right?

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Your favorite kind of transportation?

Kirk: Subaru Forester. I have a family.

Jeffrey: Dependable.

Kirk: Absolutely.

Jeffrey: Yeah, yeah. Sponsored by Subaru.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Your favorite exclamation?

Kirk: Oh, people tell me what I say. What's new is what I say to people all the time. Oh, that's another salutation. Favorite exclamation? God, I don't even know. Fuck me. Probably.

Jeffrey: That sounds good. Fuck me. Yeah, yeah, yeah. What is the opposite of the Rude Mechanicals?

Kirk: The Rude Mechanicals. We are our own opposite.

Jeffrey: What would you be doing if you weren't doing theatre?

Kirk: Oh, I would be writing novels, or reading novels, or hiding. Yes.

Jeffrey: Or hiding? Maybe both. What does ensemble mean to you?

Kirk: Ensemble means, group marriage is what came to mind. Long term, complicated conversations.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: Great. And, then what's your favorite kind of ice cream?

Kirk: I'm just vanilla. I like vanilla.

Jeffrey: Yeah.

Kirk: The reason it's the classic is because it's the classic.

Jeffrey: Right? Right? And, vanilla is a flavor.

Kirk: It is a flavor. Absolutely.

Jeffrey: I'm just saying because my wife gets mad at me because I don't do chocolate. I'm like no, vanilla is...

Kirk: Chocolate is bullshit. I don't really care for chocolate. There's this great ice cream in Austin called Amy's and they put all sorts of shit in their ice cream. And, that's one of the reasons I get vanilla is because then I get vanilla with gummy bears, or vanilla with fruity pebbles, or vanilla with they crush shit into it. You know what I really like is, you know those circus animal cookies that get dipped in icing and then sprinkled.

Jeffrey: Yep.

Kirk: Vanilla ice cream with those shits. That's good shit right there.

Jeffrey: That's where it's at.

Kirk: Yeah.

Jeffrey: That's awesome. Kirk, thank you so much for your time today. It's been a pleasure chatting with you.

Kirk: Thank you. You were brilliant.

Jeffrey: Yeah, and Amelia appreciates it, too.

Kirk: Thanks Amelia. It was nice letting me hold you. All right.

Jeffrey: I am so proud of this conversation. This podcast ties so many of our other episodes together. The ideas of efficiency that Corrina Schulenburg talks about in the Flux Theatre Ensemble episode. The growth of a company with Michaela Petro. The ensemble growing pains of who leaves, who stays, and how do I keep making as an artist with a life slash lifestyle change as Ova mentions. The idea that the space in which we work can be influential to the aesthetic fingerprint of the company Michael Fields mentions. Kirk drops how New England Foundation for the Arts is funding in a different way. And, we touch on how non Rude Mechanicals have performed their work just as Quinn at Pig Iron Theatre talked about as well.

It's refreshing to hear Kirk talk about their unique understanding of themselves in the national theatre scene rather than just the Austin, Texas scene. As well as his understanding of what regional theatres can be for the ensemble based national scene. The Rude Mechanicals are currently questioning their ensembleness which to me is what any good company should do. Part of that comes with the change of their rehearsal space, but also because they are growing as humans do with different lifestyles. They ask and answer the question how can we continue to be creative even if the work we want to do is on different timelines. They trust one another, and they have such a similar sensibility that of course they might not be in the same room together, but they still trust that the product that they are making represents the company. They are staunch supporters of one another, their family, and family's change, and grow, and evolve. And, it's a way of working that honors one another, and eliminates ego from the work. And, it's really a beautiful sense of self-knowledge as far as I'm concerned.

In the fall, the Rude Mechs are producing the next installment of the Fixing Shakespeare series with Fixing the Last Henry in which Kirk takes the lesser produced Shakespeare plays and rewrites them line by line in contemporary English making sure to update the crude words, and sexual puns, cuts it down to 10 characters, gender screws it for parody, and then edits the whole thing with no fidelity to the original text to get it all down in under and hour and a half. Whoo!

Okay, this is our last interview episode of the season. There will be one more audio essay I'm putting forth after this so stay tuned for that. I'll have more news and updates in that outro about what we might be doing next. As always, get in touch with me at [email protected], or hit my up on Facebook or Twitter at ftgupod.

All right. Thanks, and we'll see you next time on From the Ground Up.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here