Hidden Histories

An immediate bestseller upon publication in 1962, Cuckoo’s Nest, Kesey’s hallucinatory novel of a patient uprising on an asylum ward bridged Cold War paranoia with the psychedelic counterculture that would come to fruition later in that decade. Kesey wrote the book while working the overnight shift as an orderly on a psychiatric ward at a veterans’ hospital outside of San Francisco, a job he’d acquired after volunteering as a medical test subject for psychedelic drug experiments that were conducted there in the late 1950s, later revealed to have been part of a CIA-sponsored program designed to keep ahead of Soviet mind-control technology. The book’s characters were based on patients Kesey befriended while working on the ward. Dale Wasserman’s stage adaptation premiered on Broadway in November 1963, a few weeks after President Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act into law, which has been credited (not without some controversy among scholars and activists) with ushering in the long and uneven process of deinstitutionalization that would drastically diminish the number of patients indefinitely warehoused in the kind of large state-run asylum where Cuckoo’s Nest is set.

Daniel Boyle, one of Spectrum’s founding members (whose program bio mentions his childhood diagnosis with Asperger’s, Tourrette’s, ADHD, and OCD), first proposed the idea for the group to produce Cuckoo’s Nest eight months earlier, after hearing President Trump’s comments in the aftermath of the Parkland, Florida high school shooting, where he blamed the rise in mass gun violence on the closure of mental asylums.

A few days after the Spectrum production of Cuckoo’s Nest opened—and a week after back-to-back mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton left thirty-three people dead, the United States President again returned to this dark idea, telling a crowd of supporters at a rally: “We have to start building institutions again.” He then called for changes to the country’s mental health laws “to better identify mentally disturbed individuals” in order to make sure “those people not only get treatment, but when necessary, involuntary confinement.” For decades the US gun lobby has tried change the subject of public debate about mass shootings from gun control to mental health policy, despite extensive studies confirming that people diagnosed with mental illness are far more likely to be the victims rather than perpetrators of violence. But now it is not just the NRA and President Trump who are seizing on the excuse to expand the surveillance and policing of an already vulnerable population. Andrew Cuomo, the democratic governor of New York, recently proposed tying gun-control legislation to the creation of a federal “mental illness database”—the latest example of what writers and activists within the disability and psychiatric survivorship movements have begun describing as the emergence of a digital asylum.

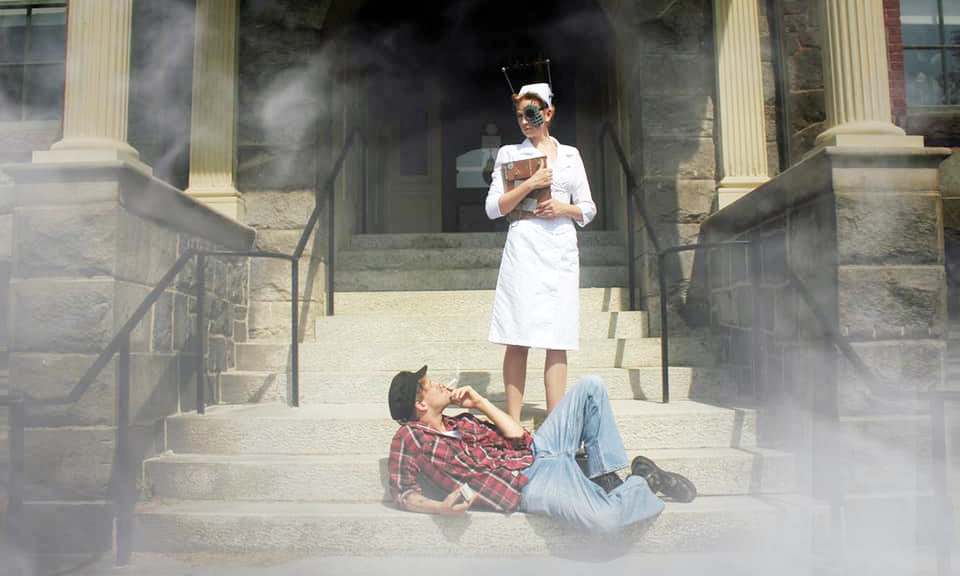

Witnessing an ensemble made up of both neurotypical and neurodivergent actors assume the roles of patients in a mental ward made for a charged viewing experience.

Cuckoo’s Nest, Now and Then

In an op-ed published on the independent news site TruthOut shortly after the Parkland shooting, disability studies scholars Anne Parsons, Michael Rembis, and Liat Ben-Moshe warned that the latest calls for a return to thoroughly repudiated mental health policies could have devastating consequences. Under the present way of thinking, they noted, “custodial mental institutions are viewed as legitimate and appropriate, rather than as a form of state-sponsored violence [which] directly contradicts the historical record.” How can returning to Cuckoo’s Nest—long a staple of high school English classes—provide the occasion to grapple anew with the ongoing effects of these histories of ableism and saneism?

Despite its enduring popularity—or maybe because of it—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest poses real challenges for contemporary readers and audiences. Many of its plot points have not aged particularly well. The seemingly voiceless Chief Bromden, whose hallucinatory inner monologues frame the narrative, is an especially grating example of the vestigial “last remaining Indian” trope. Cuckoo’s Nest is also weighed down by its painfully retrograde sexual politics: the plot hinges on depicting the ward’s inmates as passive and emasculated figures who are complicit in their own suffering and makes Nurse Ratched, rather than the male doctor or orderlies, into the ultimate authority charged with enforcing the laws of conformity.

Spectrum’s production refused to allow disability to remain a metaphorical gimmick.

Jack Nicholson’s Oscar-winning performance as the defiant, ultimately self-sacrificing protagonist Randle P. McMurphy in the 1975 film adaptation seared the character into the cultural consciousness. But it only took a few moments for Spectrum company member Teddy Lytle to shake off any lingering memories of Nicholson’s frenzied portrayal. A recent alum of the Brown/Trinity acting program, Lytle swung for the fences in the play’s first half, tearing across the stage spewing sweat and spit as he raged against Nurse Ratched and the orderlies under her command.

As McMurphy learns that he’s the only inmate on the ward who’s being held “involuntarily” and the narrative starts to churn toward its inexorably tragic climax, Lytle turned hauntingly inward. Here the production seemed to be pointedly puncturing the distinction between actor and fictional character: Lytle’s performance seemed even more resonant when considered in relationship to the raw and hilarious solo piece he performed as his MFA recital last year, distilling his private struggles with addiction and mental illness. The devastating moment when McMurphy realizes how thoroughly he’s been ensnared by the institution’s implacable diagnostic machinery became especially bone-chilling in light of President Trump’s call to bringing back mental asylums and “involuntary confinement.”

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here