Karen: Kosovo achieved independence in 2008 after the final bloody war of ethnic cleansing that marked the breakup of the former Yugoslavia. Your work has been described as acts of “literary reconciliation,” can you explain this?

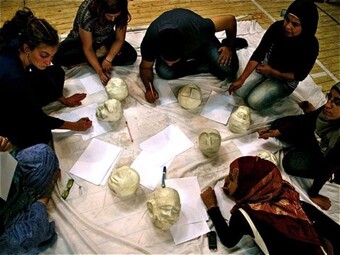

Jeton: After the war, the level of hatred was huge, in both Kosovo and Serbia. With other Kosovar intellectuals and artists, I became involved in several cultural projects. Somebody had to start that. We were the first to collaborate with Serbian artists on several collections of translations of fiction and drama between the two cultures and in coproducing and exchanging theatre work.

People saw this as if we were collaborating with enemy, but now, after ten years, our work is seen mostly as a pure cultural act. Still, there is no common sense of shared history of the past. In Kosovo, Albanians see themselves as the victims. In Serbia, Serbs see themselves as the victims. Of course, with Serbian intellectuals, you can discuss any matter related to the war and they are open and aware of the crimes that the Serbian military forces have committed in Kosovo, but the majority of the population on both sides does not want to enter into this dialogue.

But, if everybody is a victim, then who was the one to commit crimes? Responsibility and confrontation imply recognition of what happened. This is intellectual responsibility, and this is the contribution of intellectuals for reconciliation.

Karen: Where were you during the war?

Jeton: I was young, still a student, and I sometimes wrote speeches for the local commander of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in my hometown. Some war propaganda. I wasn’t exactly in the army—I wasn’t doing the fighting, but I was working with the fighters. It felt safer to be with them.

I was also often thinking of my Serbian elementary school teacher Bora and asking myself: Would I be able to kill him if I met him? Would Bora be able to kill me? The answer in both cases was “No!” So, focusing on this bit of “humanity” in that period of total dehumanization helped me easily connect to the cultural dialogue with Serbian artists after the war.

When it was over, I was writing plays about war and I believed that I was helping myself, healing my own traumas, but also, in a way, documenting the war and making some sort of war chronicle. But my writing at that time was characterized with pathos, with the inability to see the war with more colors than just black and white.

When that happens, you come to a situation where you know what you are writing is not what you would want to write, but on the other hand you have no force, no capacity to write differently, to see things from another perspective. I worked hard in order to change how I wrote. It was like coming to see your drama as somebody else’s drama. I escaped with a lot of effort into a new way of writing.

This was important for me because then I was free as a writer. Then I was not only fighting the other demons, the demons of “the enemy,” but my own demons as well. I was fighting for my own personal freedom, but also for the freedom on the stage. I wanted to be able to write what I wanted to write and have it seen by an audience.

My play One Flew Over the Kosovo Theatre was cancelled by the government. A minister of culture intervened and called off the production.

We couldn’t allow the actors’ faces to be seen clearly on the poster. Because yes, we were afraid.

Karen: That play is a comedy about a group of theatre artists commissioned to create a piece of entertainment to celebrate the independence of Kosovo, but over the course of their rehearsals they unmask the enormous corruption within the new government.

Jeton: Yes. At the beginning of our rehearsals, we sent out “fake” press releases saying we had the full support of the government to produce the play about Kosovo announcing its independence. These releases were published and people said, “You are working with the government?” But the play was actually critiquing the government and the press releases we sent were meant as some sort of public interventions. One said that the only five copies of the play had been stolen, but the actors had already learned their lines, so we could continue. It also said that we suspected Serbian spies or the Russian KGB were trying to prevent the play.

The Kosovo government did not believe this, of course, but closer to the premiere they desperately wanted to cancel the play. In the end, we did it, but it was a fight. Ambassadors to Kosovo from Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, who were our supporters, told us that we must not give up. They urged us and supported us as we fought to do the play.

People also said the play was funded by Serbian money and it was an “anti-national” play. Later, when we toured the same play in Serbia, the Serbs said it was a provocation because they did not recognize Kosovo as an independent country. In Serbia, as in Kosovo, we had to often invite the police to protect the theatre during the performances.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here