My Brother’s A Keeper

Storytelling With Funk Aesthetics

When I think about funk music, I envision James Brown, Sly and The Family Stone, and Kool and The Gang, grooving, crafting, and breathing life into dance floor anthems, and encouraging us, sometimes all in the same song, to dance, protest, hump, live, and love hard as hell.

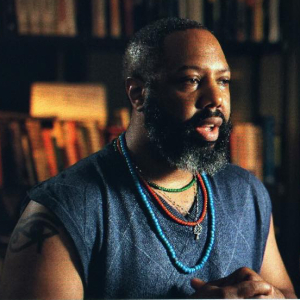

When playwright, director, and activist Dr. Herukhuti thinks about funk music, it’s often as the organizing framework for his cultural work and activism. Growing up with parents who were Black Panthers and grandparents who met while working as activists and organizers, funk was always present in his life, woven into his cultural sensibilities.

Over time, he began exploring and developing the concept of funk music as a radical, transgressive approach to examining and representing Black sexual politics—a new way to dive into and shake up our ideas around attraction, love, sex, and gender roles. He was eager to contribute meaningfully to the struggle for Black liberation.

Inspired by his lifelong love affair with the art form and the increasing use of jazz aesthetics—ensemble, improvisation, the bridge, and the break—in theatre, Herukhuti wondered, “How can I apply the funk to theatre? What would that look like?”

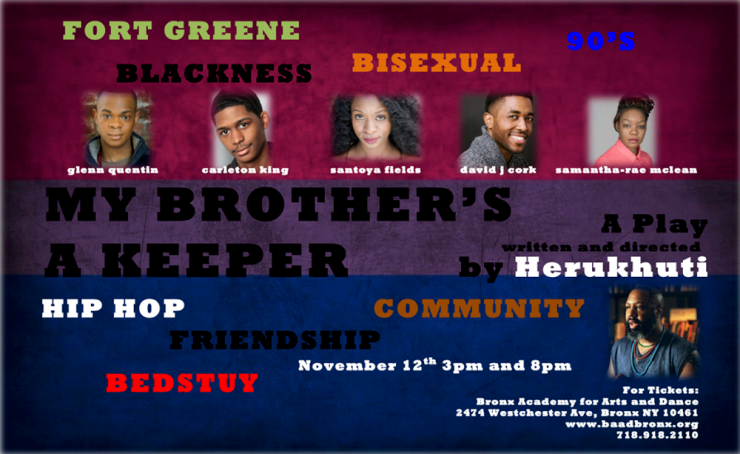

The result was My Brother’s A Keeper, a twenty-something coming of age story that depicts a weekend in the lives of five friends—Cecil, Mona, Kevin, Basil, and Charlene—figuring out love, gentrification, friendship, HIV, and sexuality in late 90s Fort Greene and Bedford-Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. After a member of the crew begins to question and explore their sexuality, biases (and infidelity) threaten their bonds, and everybody is forced to confront their identity issues.

It was a joy to see Black male sexuality explored without the usual sensationalism or tropes.

I had the pleasure of seeing the second of two workshop performances at the Bronx Academy of Arts and Dance as part of their ongoing 2016 Blaktinx Festival. It was a joy to see Black male sexuality explored without the usual sensationalism or tropes. Watching characters that talk and act like humans I know versus stereotype-based caricatures is always refreshing.

Modern public representations of Black male bisexuality are infrequent in society and pop culture and nearly nonexistent in theatre, so it’s refreshing to see such a careful depiction of an often-overlooked group. The nuances here when addressing biphobia and sexual diversity in Black American and Caribbean-Americans communities add authenticity and complexity. These folks feel like people I know, and I appreciate that.

As Herukhuti’s first play since making his debut as a playwright in 1996, My Brother’s A Keeper incorporates two other key elements of the funk that has shaped much of his life: content and form.

Here, the funk aesthetic manifests in the content and form of Herukhuti’s work. Content-wise, like funk music, his approach to theatre integrates the political with the sexual and the social. This work disrupts respectability politics. These characters are not perfect. “These people are multidimensional, and complicated. They have aspects that are not one note,” he says. “They’re not monotone.”

This work disrupts respectability politics. These characters are not perfect.

Funk’s influence also reveals itself in Herukhuti’s approach to the form, specifically the designing and directing of this play. As in funk music, his use of syncopation and silence create dynamic moments that adds an element of intrigue. In rehearsals, it’s not uncommon to see him snapping, counting out beats between action to achieve just the perfect pacing and flow. Rhythmically, he plays with the typical expectation of where or when, “in the midst of a conversation or scene, an action, sound, or response should happen. Sometimes where an action is anticipated, there is deliberate space or a beat.”

Elsewhere in the production, he employs polyrhythms (in this case: actors operating at different rhythms) to create funky syncopations within a scene. The actors play with syncopation to provoke audience responses.

When it came to conceptualization this work, Parliament Funkadelic was a big inspiration.

Their albums came from people recording and existing in one space for twelve hours, twenty-four hours. The result is a special funk, a gumbo created when you have immensely talented artists sharing an intimate area, coming, going, eating, interacting, experimenting, and working together for a long time. It’s beautiful.

Speaking of his own creative process, Herukhuti references with reverence those marathon groove and recording sessions that spurred Parliament Funkadelic’s sonic masterpieces. Whereas staging a production in your living room could be seen as a major limitation, he considers it a benefit. The forced intimacy of piecing a show together in Herukhuti’s living room fostered closeness among the cast and allows all those creative juices to stew together to produce a rich, textured piece of work.

Echoing a sentiment shared by stage veteran Viola Davis, Herukhuti acknowledges that so often the work Black actors have to choose from is stereotype-driven, resulting in flat, one-dimensional, unrealistic characters (or “types”) instead of people that act and feel like real people. It’s why it was important that he humanely portray both the mundanities and the complexities of Black life.

I had to explore those undiscovered aspects of us and our humanity. And share stories—regular black folks doing polyamory, navigating biphobia, exploring their sexuality, for example—that we rarely see done right if at all, on stage or on screen. And I had to do it in a responsible, authentic way. It was both a challenge and a gift.

Thankfully, in addition to writing and directing plays, Dr. Herukhuti is a sexologist. Studying people through the lens of sexuality gave him invaluable perspective of the world and how people worked, social dynamics, and human interactions and motivations.

“When I’m writing and directing, I often draw from my work as a social scientist. I’m thinking about what I know about how people interact and behave, and the complexities of communication, like subtext and saying one thing and doing another,” he says. “I’m much more clear about our complications and internal contradictions.”

Among the many issues tackled here, My Brother’s A Keeper explores the effects of gentrification in 90s Brooklyn, and how “beautification” and rapid development affected these communities on a social level. The influx of new neighbors with new cultural ideals and so-called “improvements” that resulted in rising property rates altered not only the residential and cultural makeup of a neighborhood, but also eliminated historic places of fellowship.

In a scene that explores infidelity and the vulnerabilities of polyamory, Charlene (Samantha Rae) reminisces with Kevin (Glenn Quentin) and Cecil (David J. Cork) about the beauty and cultural significance of cooking among Caribbean communities. Where she comes from, cooking for someone is akin to “working in the tradition of healers, griots, root workers of the ancestors.” The Jamaican/Vincentian-American restaurant owner gives some insight on how skyrocketing rents and disappearing mom-and-pop spots affect the surrounding communities on a social level.

“Restaurants are an essential part of our communities. It’s where everybody comes together. Men go to the barbershop, the women to the parlor, church people to church. Party people to the club,” she explains. “But everyone comes together to eat. And they socialize with their neighbors.”

Today in Bed-Stuy, it is still depressingly common to see restaurants that fed generations of your family be unceremoniously replaced by yoga studios, juice shops, and acting schools for dogs. As New York City's two-time mayoral candidate Jimmy McMillan would say, the rent is (still) too damn high.

The first spark for this play came at an Emerging Voices LGBT writing retreat for the Lambda Literary Foundation. At the time, Herukhuti was exploring the possibilities of a polyamorous relationship with his girlfriend, and he struggled to find relatable examples of this type of union.

“I didn’t have any models of Black folks doing polyamory, other than the image of a man with multiple wives. I had no models that weren’t patriarchal or designed to serve men,” Herkukhuti says. “There was nothing about two people coming to appreciate and embrace the fact that they could experience pleasure with multiple people and it not affect or diminish their love.”

That hunger for representation and the biphobia he received when discussing his bisexuality with Black gay men were the driving forces behind My Brother’s A Keeper. This play was a way to grapple with and speak back against ignorance, prejudice, discrimination, and oppression he faced.

With so few prominent openly bisexual Black men—New York Times columnist Charles Blow is a rare example—this play expands and adds depth to necessary conversations around the beauty of embracing the full spectrum of sexuality.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here