A (New) Vision Grows in Harlem

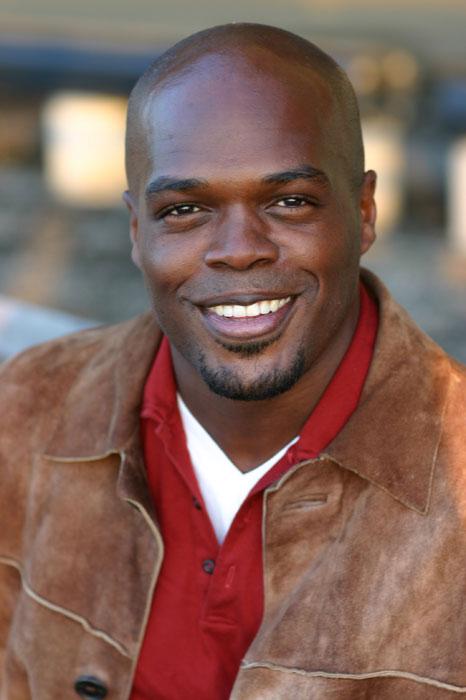

Conversation with Ty Jones

“You need to audition for this. It’s a great play.”

This is the insistent appeal issued to me by a friend two years ago after she received a casting call for the Off Broadway workshop of Radha Blank’s SEED. I’ll admit, I hesitated. As a classically trained African American actress, the years of fighting to discover and land roles that I loved had left me hurt and wary. But after reading the script, it was clear that SEED had it all: wonderfully complicated characters, gorgeous language, breathtaking plot twists, and a call to action so insistent it made my heart ache.

So, I auditioned. Five days later, I was offered the role and one of the finest creative experiences of my career began.

I find myself thinking about this sequence of events—the email, my battle-weary distrust of my own professional community, the surprising dignity and accessibility of the SEED audition process—as the time approaches for my conversation with Ty Jones. Now in his third year as Producing Artistic Director of the Classical Theatre of Harlem, the co-producers of SEED, Jones has a lot to do with how I ended up in the show. An artist himself, Jones recognizes the incredible barriers to entry into the profession for artists of color, and firmly maintains an open door policy, encouraging actors, writers and directors to take leadership roles in developing readings, productions, and neighborhood partnerships.

How this formula is transforming the Harlem community, both for artists and for local residents, was the topic I most wanted to explore with Ty during our conversation.

Bridgit Evans: For those people who may not know Classical Theatre of Harlem's trajectory, can you give some background on why the company was founded?

Ty Jones: CTH started in 1999 and the lion's share of the credit for its existence today is because of the Harlem School of the Arts. I kind of liken it to, imagine in a community if there's a baseball field that isn't being used. And you know, the grounds haven't been kept and you have a group of people who are like, "Look, we have a field here. We have something that could be of use, that could be of service to folks in this community." And you have a groundswell of people who choose to play, who participate in it, many of them for free, and present a show for the community. And that's essentially how things started with Classical Theatre of Harlem. This company's been built on the backs of young, hungry, vulnerable, passionate, talented artists of color. And I would say that CTH essentially really started to flex its muscles around 2003/2004 when more experienced actors, ones who had graduated from graduate programs, started to join the company. And as we've continued to grow and do these great plays and have a great mixture of some of the nation’s most experienced actors, I think people started to really take notice of this young company up in Harlem.

The vision I see is that I believe that CTH can be for Harlem one day what the Public Theatre is to downtown or what Lincoln Center is to midtown. And this can't be just an administrative-led type of endeavor. The artists have to believe in that vision first, because those are the people that you are going to rely on to keep you relevant while you get to that place where now folks can graduate from school and know they can go to the Classical Theatre of Harlem as an artistic home.

Bridgit: And where has it arrived today?

Ty: We’ve had some growing pains where we needed to learn how to become a first class company on the administrative side as well as the production side. And so we were able to enlist consultants who instructed us on governance, essentially how to run a company.

One of the things that I've learned along the way is about cultivation. That's what it ultimately comes down to. We have to be able to reach out to our community because they're the ones that are essentially going to say, "Yes, we need you. We want you. And we want you to stay and we need you to stay." I think there are a number of challenges that come along with that because you can't be all things to all people. But what we've done I think is a bit unique because we will do your cannon of classic plays. And then what we have asserted with our Future Classics program is that there are plays that have yet to stand the test of time, but we feel that they will ultimately become part of that cultural lexicon of great classic plays. So we like to dust off the word ‘classic’ a little bit. We also love, when we can, to tip our hats to the forgotten years of a number of artists, particularly writers of color in the '60s and '70s, who were writing these extraordinary plays that weren't seeing any real fruition towards production. So we like to try to look through that historical content of these great plays and try to put them on their feet.

Bridgit: Why Harlem?

Ty: That's a good question. I think Harlem, for many years, would be considered sort of a depressed or an enervated community or hamlet in Manhattan. And whenever, regardless of the situation, whenever there are situations or circumstances where people are in need, often times you see some of the greatest and most extraordinary things happen out of places that are so unexpected. And I think Harlem got beat up to the point where we were at that place. It was time for something great to happen.

And I think with the new investment that's been heading up to Harlem and the Washington Heights area, I think we're starting to see that momentum again. And people are looking at Harlem as a destination place for restaurants, for cultural visitations.

I firmly believe that the core of any revitalization of any community is the arts. I think a perfect example here in New York is the Upper West Side—at one point in time not the most neighborly place to be in. And then you have the Vivian Beaumont at Lincoln Center and that extraordinary investment from Rockefeller. I mean the Vivian Beaumont at one point in time was going to be an indoor skating rink because of the troubles that they had gotten into. Rockefeller came in, of course a number of other funding sources were cultivated, and now look at the Upper West Side, probably one of the most—let's put it this way: the real estate there isn't cheap. You know? And Lincoln Center is the core of that.

I believe that, with the community of Harlem emerging, it takes a village of business, political, community and cultural leaders to find substantive and creative ways to engage the challenges of being a sustainable institution, an arts institution in any neighborhood. With Harlem, it's emerging. It's evolving right before us. Some people call it gentrification. Some people see it as a revitalization. But I think both would agree that to move forward we've got to say that Harlem and its community matters.

Bridgit: Classical Theatre of Harlem is one of the most resourced and recognized theater producers in the Harlem neighborhood. In what ways does CTH collaborate or bolster the efforts of younger companies that may be operating at the Off Off Broadway level?

Ty: The simple answer is that social media has been a necessary tool for small companies, including ours. And it is a great way of bringing together companies that have similar missions to help one another out in bringing audiences to their productions or to their shows. One of the companies we've worked with recently was the Hip Hop Theatre Festival. We worked together on co-producing SEED. We are always in touch with the folks at the New Black Theatre Festival. We do e-blasts for one another. We even exchange artists on our reading series. The list goes on and on and on. It's absolutely important for all these small companies, I believe, to work together in order to sustain themselves.

Bridgit: And how do you sustain a company in Harlem?

Ty: What it comes down to is cultivation. I recall a conversation that you and I had about how upwards of 50 to 60 percent of foundation money is going to anywhere between two and five percent of arts institutions. And those institutions happen to be institutions that have budgets of five, six, seven, a million dollars or more. And so there seems to be some inequality there.

Now there's a couple of ways to look at that. There seems to be a sort of insensitivity, if you will, of not recognizing all this other great art out there that might be produced by women and artists of color. And then the other side is that these institutions have done well at cultivating. And younger, smaller companies would do very well to learn how to cultivate within their own community. And so for myself, for example, I've had talks with Oskar Eustis at the Public Theater. I've had talks with Bernie Gersten over at Lincoln Center. I want to learn how in the world with these budgets of $20 to $30 or $40 million, how you do it? How do you make that happen?

Bridgit: CTH is very much a company that was born and is driven by the leadership and energy of performing artists, not administrators. As the company has grown, you mentioned the growing pains of being an artist-driven company that is now absorbing a lot more expertise around administration and governance. I'm wondering what you feel is the viability of CTH, as it continues to grow in Harlem, to continue to be an organization that's led by artists versus administrators?

Ty: Yeah, I do believe that it has to be led by artists. But these artists need to make sure that they have a certain skill set on the commerce side. I think that that is not the only, but definitely a formula, towards some success. The companies that are tiny like ours, we really don't have the room to fail. It's interesting, when I brought up Lincoln Center or you bring up the Guthrie or even the Public Theatre, when those big foundations came in to help them out or the city came in to help them out, they give them room to work out their kinks, work out their vision over a few years until they were able to sustain themselves. So let me start off with the vision. The vision I see is that I believe that CTH can be for Harlem one day what the Public Theatre is to downtown or what Lincoln Center is to midtown. And this can't be just an administrative-led type of endeavor. The artists have to believe in that vision first, because those are the people that you are going to rely on to keep you relevant while you get to that place where now folks can graduate from school and know they can go to the Classical Theatre of Harlem as an artistic home.

Bridgit: If you had the opportunity to make three recommendations to funders about why and how they could invest in developing the theater environment in Harlem, what three things would you encourage them to consider?

Ty: Another great question. I believe that, with the community of Harlem emerging, it takes a village of business, political, community and cultural leaders to find substantive and creative ways to engage the challenges of being a sustainable institution, an arts institution in any neighborhood. With Harlem, it's emerging. It's evolving right before us. Some people call it gentrification. Some people see it as a revitalization. But I think both would agree that to move forward we've got to say that Harlem and its community matters. So for those that are, let's say, on the gentrification side, they have to be able to say, "Okay, as we move forward we have to make sure our cultural treasures are implanted and remain alive and vibrant." And then the folks who are sort of part of the new gentry and the newer investment that's come into Harlem, they know that in order for the community to thrive you need the arts and you need to make sure that you engage all those folks that I mentioned before in several different communities.

And I feel like with CTH, we're positioned to bring these communities together. I'm excited actually about that opportunity. Our audiences are diverse economically, racially, gender-wise, everything. And through the arts, if we can get these people together, talking, fellowship, I think extraordinary things can happen. And it's important that we have a place to store our cultural treasures because there are some hard lessons that Harlem has gone through and lessons that we've all learned. And if we don't want to see that sort of thing happen again we have to make sure that whatever side of the argument that you're on, that from here on out we have to say that Harlem matters.

Bridgit: Ty, thank you so much for talking to me.

Ty: Thanks for the conversation.

Mr. Jones is the Producing Director of the Classical Theatre of Harlem. He was recently seen in the critically acclaimed production of ENRON. His Broadway debut was in the role of Lt. Byers in Judgment at Nuremberg, and was also seen in the Tony Award-Winning production of Henry IV and Julius Caesar with Denzel Washington. He won an OBIE Award for his portrayal of Archibald in the revival of the critically acclaimed Off-Broadway production The Blacks: A Clown Show. Also for the Classical Theatre of Harlem, Ty received Audelco Nominations for his performances in Macbeth, Trojan Women, Ain't Supposed to Die a Natural Deathand won Best Actor for his portrayal of Nat Turner, in Emancipation: Chronicles of the Nat Turner Rebellion. As a writer, Ty Jones' play Emancipation: Chronicles of the Nat Turner Rebellion, premiered for the award-winning Classical Theatre of Harlem. Mr. Jones received his MFA from the University of Delaware’s PTTP Program.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

This is one discussion about Harlem arts and its institutions that makes practical sense. Thank You