How do we continue to create amid crisis? Over the past few weeks, this question has been on the hearts and minds of many theatre practitioners around the United States and other parts of the West, where theatre tends to rely on a privileged system of access to physical spaces, resources, and bodies. Ongoing responses to COVID-19 have complicated things, to say the least. Seasons are being cut short, gigs are being canceled, and Broadway has shut down. HowlRound’s recent discussions on ways of gathering and artists in a time of global pandemic attest to the uncertainty of the moment. And because of this uncertainty—at the same time that the United States continues on an outbreak trajectory matching the direst predictions by public health officials worldwide—it is not clear when or at what rate the situation will improve. We are left with playwright and poet Bertholt Brecht’s “dark times.”

But, of course, the concept that underpins theatre is possibility. (This is not to say that it is always positive possibility, but possibility nonetheless.) Such possibility has reasserted its relevance, not least in a recent writing, performance, and production experience I had with Washington, DC’s Convergence Theatre. At the exact same moment that the pandemic became real, the experience of moving my show, Snapshots, from physical to virtual space—resulting in a livestreamed performance on March 27 that was only available through HowlRound TV—can offer lessons for others struggling with similar challenges.

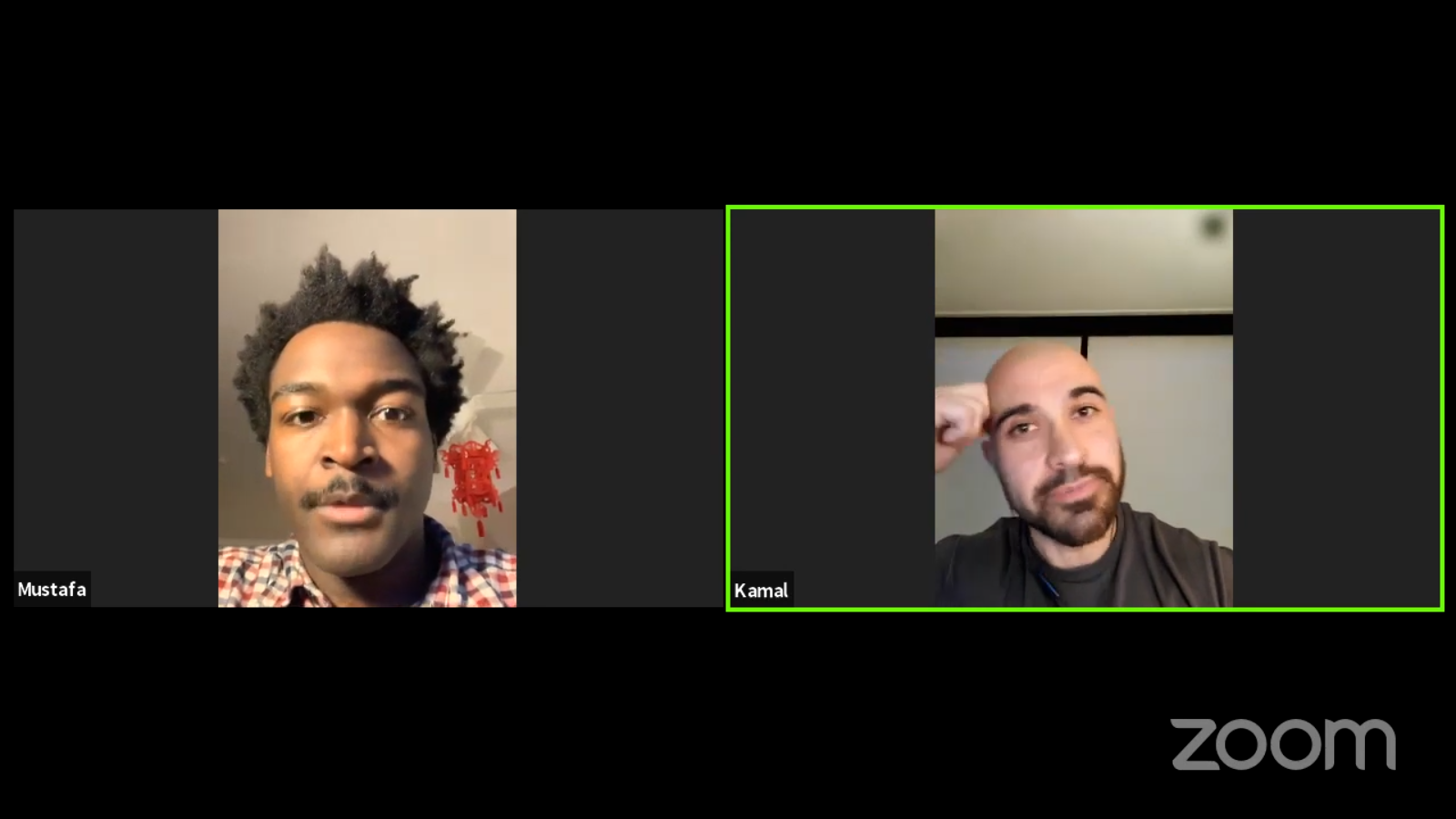

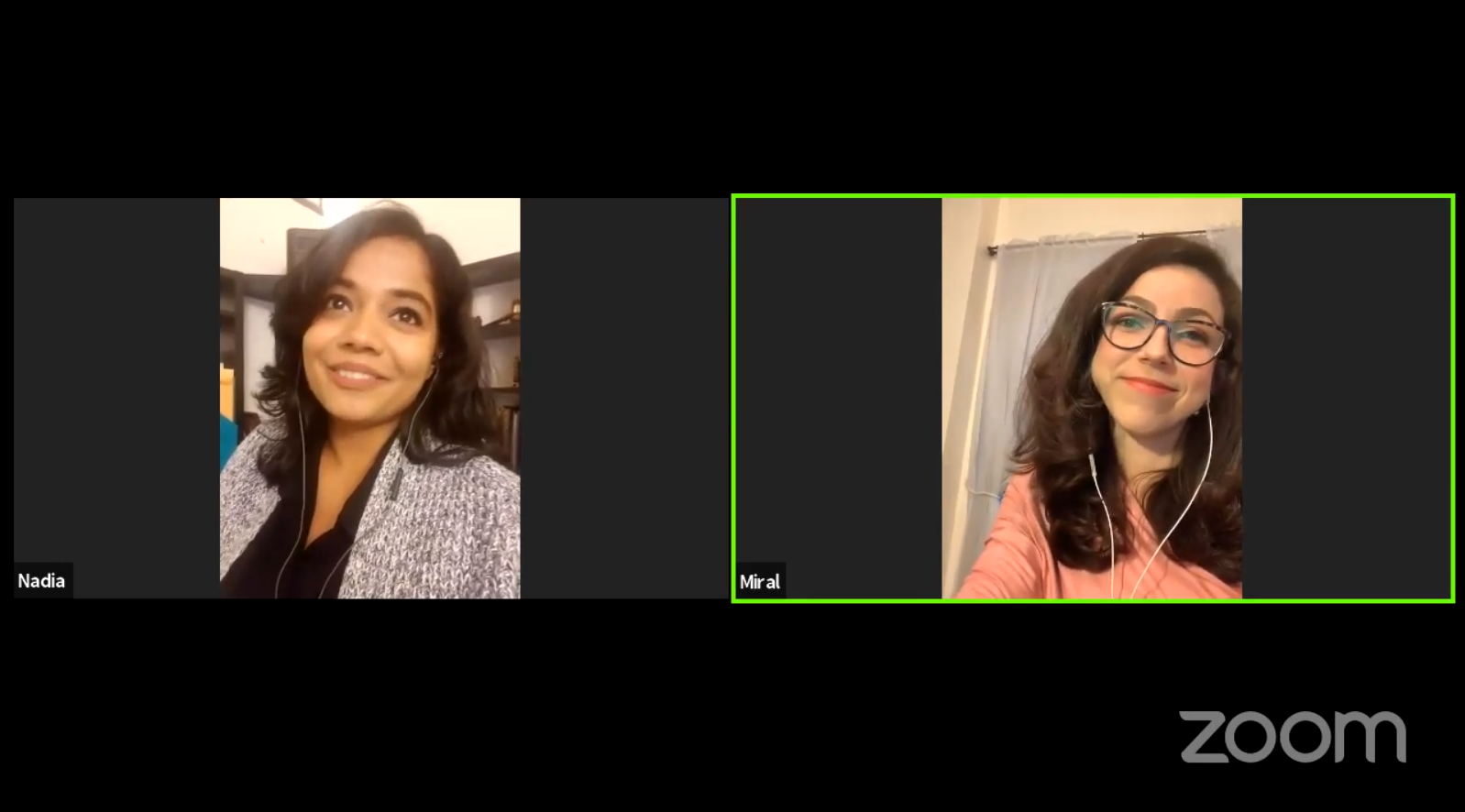

Snapshots is a play I wrote while living in the United Kingdom. It examines the intersection of Islam, sexuality, colonial history, and cultural appropriation. Snapshots was first written as a series of phone calls between four characters living and working in different parts of the world. The piece spun off from my involvement with Memories of Partition, a 2017 monologue-writing project with Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre (RET) about the legacy of the 1947 Independence and Partition of India. Through that project, Snapshots’ main character, Mustafa, came to life as a Muslim man of color questioning his sexuality while talking on the phone to his lover. The monologue was ultimately censored by RET for its strong language and sexual content. Convergence Theatre—a nomadic and multidisciplinary theatre collective with which I’ve been associated since 2015—has since become a home for the work, quickly adapting as the piece and everyday life have twisted and turned. Indeed, it is actually because of the pandemic that Snapshots has a significantly wider potential, reach, and impact than would otherwise have been the case.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here