The Theatrical Gitano Expression of Gitanismo of the Nineteenth Century

Although the affinity for Gitanismo—a form of European cultural oppression against Roma people, which lead to an inaccurate Romani stereotype—was born in the second half of the eighteenth century, it was throughout the nineteenth century that it found its place in theatre.

The Gitanismo went from being a disruptive anti-enlightenment and anti-European trend for the wealthy classes of Spain and Europe (where there was specific performance, song, and dance à la Gitano—the Gypsy way) to becoming an almost-obsessive presence in the main theatres of the country through their roles in dance and theatre performances. This was also the time when Gitano characters found places in major historical operas, above all in Carmen by Bizet, based on the 1845 novella by Prosper Mérimée Merimee. This marked the beginning of the path of European obsession with sexualizing Romani women.

There were two popular subgenres whose dramatic structures served as the backbone for what was then known as teatro Gitanesco: the theatrical tonadilla—a short, satirical musical comedy popular in eighteenth-century Spain—and the sainetes—a one-act tidbit, farce, or dramatic vignette with music. There are dozens of works during this period with Gitano characters—with titles and texts in Caló, the Spanish Gitano ethnolect—that feature and enforce crude caricatures of Gitanos, strongly contrasting the real situation of Romani people in Spain. The social imagery of Gitanos in “theatre of the poor” shows unworried Gitanos only interested in love affairs, robbery, and parties. The best-known example is El Gitano Canuto, o día de toros en Sevilla, written in 1816 by Juan Ignacio González del Castillo.

However, all of this theatrical exposure over a century and a half had consequences for Gitano artists, who felt compelled—or socially condemned—to look and perform like these images, something that is still present nowadays for Romani people. However, in more private settings, and thanks to Gitano artists like Lita Claver, who worked in alternative genres like cabaret, the theatrical Gitanismo found one of its counter-narratives by reversing all the happy and naive aesthetics to more dangerous and controversial ones.

The Gitano Individual in the Twentieth Century

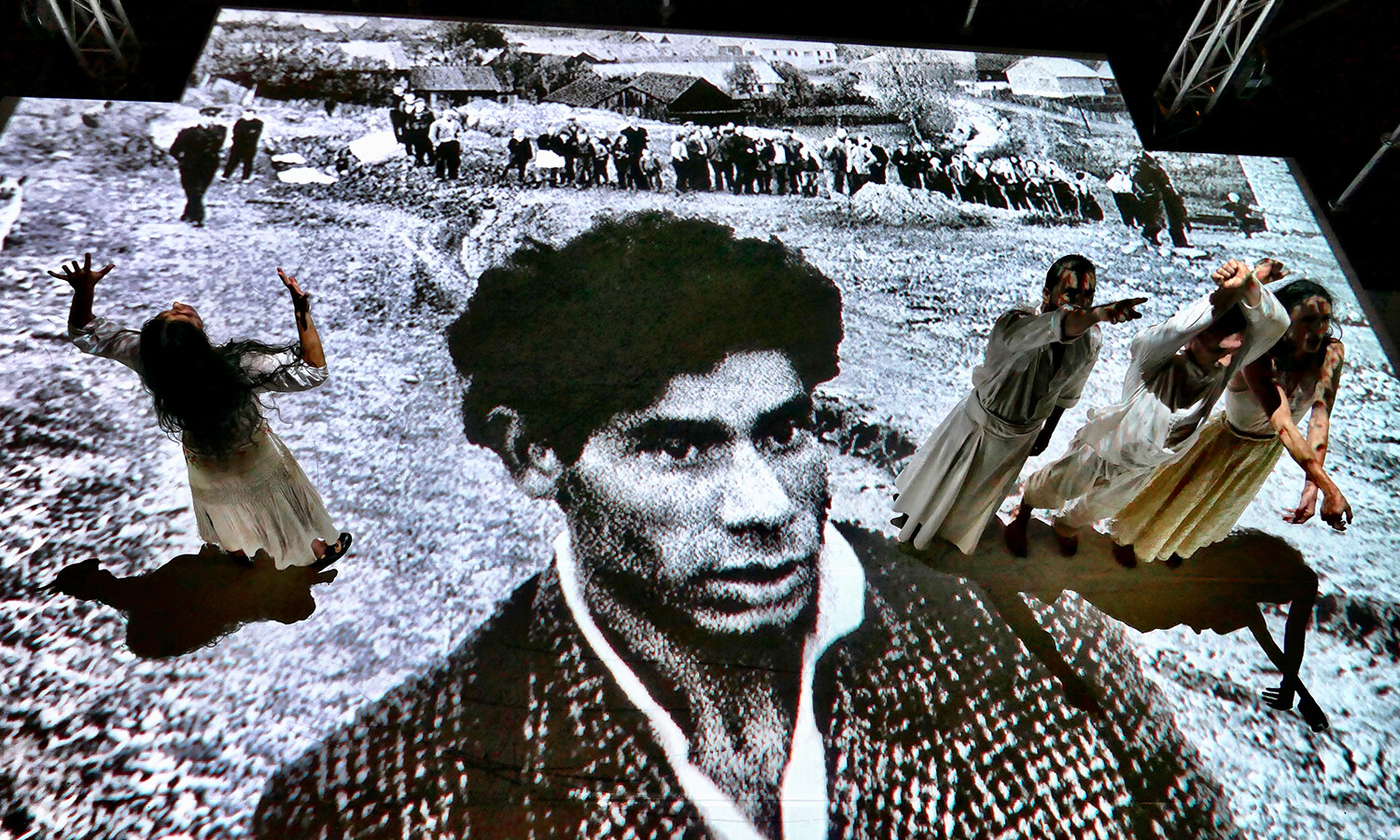

The appearance of the flamenco genre in the 1860s, which partially stemmed from teatro Gitanesco, opened the doors to a type of subjective theatrical expression that fought against the stifling corset of mediocre fiction in which Gitanos were inaccurately depicted. This kind of performance took risks with lyrical and individual expression, breaking the fourth wall with a raw and exposed aesthetic. It coexisted with other forms that continued to use the image of the Gitano as “other,” but flamenco helped Gitano artists excel in foreign environments with their own personality.

The reclaiming of the Gitano identity came at the end of the Franco dictatorship, when flamenco became a dignified art form.

During a big part of nineteenth century, many Gitana artists performed anonymously, something depicted in many of the posters from the time period, where they were announced as simply “famous Gitana dancers.” By the end of that century and during a big part of the twentieth century, as flamenco became a highly demanded product—which lead to the professionalization of many artists—many contemporary Gitana artists were leading companies and touring shows as singers, dancers, or entrepreneurs.

Some examples include Pastora Pavón Niña de los Peines, Imperio Argentina, and Carmen Amaya. On top of creating their own work, these artists were featured in classic pieces by non-Gitano writers, like Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca—an inclusion, yes, but not the ultimate signifier that would make the Gitano artists accepted as contemporary scenic and musical creators.

Although the situation of Romani people in Spain was still harsh, the creativity and professionalism of the women allowed them to excel in a predominantly male-led world. Carmen Amaya became an international symbol for Romani artists.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here