Power vs. Truth in Belarus Free Theatre’s Being Harold Pinter

“As a citizen I must ask: What is true? What is false?” —Harold Pinter

One year before he passed, Harold Pinter, an ardent supporter of Belarus Free Theatre (BFT), sent a postcard to the company scrawled with the words “I am furious” when they and their audience were arrested by the authorities at a performance in Minsk in 2007. At the post show discussion after BFT’s performance of Being Harold Pinter at the Young Vic in November 2015, Michael Attenborough, a trustee of the company, commented that Pinter was “very good at holding onto his anger.” In fact, his anger at social and political injustice didn’t waver as he aged but grew in magnitude.

It grows here too in this 100 minute exploration of some of Pinter’s best known work, palpably demonstrating the increasing outrage and individual and collective pain that drive so many of Pinter’s and BFT’s plays. Expressing the struggle between the maintenance of power and truth by incorporating excerpts from his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, the company, along with adapter and director Vladimir Shcherban, parallel an exploration of Pinter’s indistinct working methods. Pinter notes: “I have often been asked how my plays come about. I cannot say. Nor can I ever sum up my plays, except to say that this is what happened.” In Being Harold Pinter BFT also explores Pinter’s concerns with domestic abuse that, in his later plays, metamorphose into an interest in political violence, developing consciousness, and citizen responsibility.

Being Harold Pinter was part of Belarus Free Theatre’s Staging a Revolution, a two-week festival of performances and discussion platforms from Belarus Free Theatre to mark their 10th anniversary in 2015.

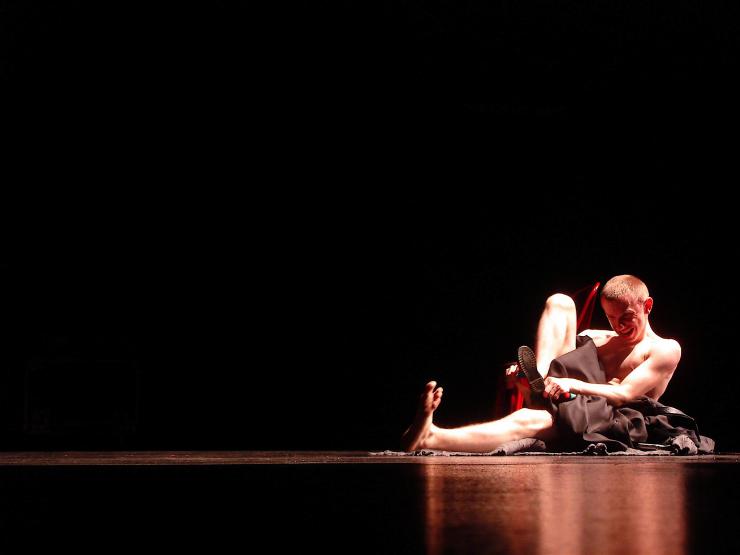

Citizen obligation is perhaps imposed on the audience as soon as they enter the Young Vic’s performance space. But when at the entrance, a man in guarded jocular fashion impresses a stamp upon our hands, is it a passport for truth or a symbol of the maintenance of power all authorities and politicians try to have over us? We must decide. Curiously, even less revealing of BFT’s purpose, is the stage: its schematic design is like that of a David Lynch film, populated with men and women androgynously dressed and set against a back drop of imposing, faceless black curtains. It feels like we are entering a place of magic, whose underbelly threatens a nightmarish violence where we are not sure what to believe, and Pinter, brought to life through actor Aleh Sidorchyk's intense and incensed incarnation, grasps his walking aid as if it is also a wand that can wave things into being. To infer that it is not what we have, i.e power, but how we use what we have that’s the problem, we later see this benign aid transforming into an instrument of torture when placed in the wrong hands.

Pinter falls and another actor sprays red paint on Sidorchyk’s head to symbolize blood. This action articulates a point about the pictorial representation of art and its power. It means blood, but it’s also just paint. “A thing is not necessarily either true or false; it can be both true and false” wrote Pinter at the beginning of his Nobel Prize Speech.

Violence, its partner power, truth, and falsity, dominate the mood of the play. In excerpts from Homecoming, rabid domestic abuse is the framework for an encounter between father Max and son Lenny, who snarl their unconscious words at each other. Words are as integral to the piece as what is not said (and Pinter’s all important pauses), and BFT’s fast paced delivery shores up this notion, a welcome stylistic choice that flies in the face of numerous traditional realistic interpretations. We may not physically attack each other, but what we say and imply in this furious rhythm is just as murderous, and maintains power. The question is, how unconscious of themselves and the reasons for the way they behave are the characters? And therefore, how much can they be held to account?

By the time we get to Mountainside Language some sort of clarity is emerging. The quest for truth is made easier as we understand that the authorities know what they are doing and why, and even they are bored by it. And certainly, the victims are aware. We see how linguistic oppression, imposed by the state (Belarus dictator Alexander Lukashenko stigmatizes the speaking of Belarusian) limits and controls individual freedom, even when one refuses to play the game and silence is the ethical weapon. “Language in art remains a highly ambiguous transaction, a quicksand, a trampoline, a frozen pool which might give way under you, the author, at any time” says Harold Pinter in his speech. Nonetheless, what is true of art is also true of life, of politics and our politicians.

Little scenes from One for the Road and The New World Order further explore the ambiguity of language and how it can hijack meaning. For example, a prison warden turns into an incense-burning Catholic priest. His finger-pointing turns into the sign of the cross and his torture morphs into verbal suggestion.

But it is in the excerpts of Ashes to Ashes where we experience the choking stranglehold of the maintenance of power in all its glory and where its revelation, which paves the way for the beginning of truth and consciousness, deals a fatal blow.

But it is in the excerpts of Ashes to Ashes where we experience the choking stranglehold of the maintenance of power in all its glory and where its revelation, which paves the way for the beginning of truth and consciousness, deals a fatal blow. Watching this the day after the Paris and Beirut terrorist attacks, it could not have felt more pertinent. For what happens to an organism when its eyes are truly opened and it bears witness to a reality so overwhelming, it believes nothing can be done, and is anyway, in other ways, itself struggling to exist? Here there is a need for a feeling of collective guilt and of powerless responsibility in the face of awful truth. A woman grapples with an aggressive man (who may or may not be her therapist/lover/husband) and the terror that is going on in the world around her. “How can one live with it?,” Pinter and BFT seem to be asking. The woman is drowning in remembered acts of tyranny and abuse that are not hers and that she cannot have directly experienced. Her lover remains in a state of ignorance, under the influence of the power of the politicians, but the woman, who now knows the truth, is unable to cope. When BFT end their play with statements from the cast about their own experiences of abuse and torture back in Belarus, it feels like something has turned full circle and that elusive dramatic truth meets objective reality.

The company doesn’t just fight ‘state censorship’ which they suffer in their own country, but also fight ‘self censorship’ an illness they think is prevalent in the western democratic world.

All the while, Harold Pinter’s dark brooding eyes bear down upon us from the back wall of the Young Vic’s Maria Studio. What now? He seems to be asking.

In his introduction at the beginning of the play, director Vladimir Shcherban asserted that BFT wish to carry on the work of Harold Pinter and that it is important to “smash the mirror to find the truth.” In the discussion after the show, BFT maintained they don’t know the word “impossible” and guard against any form of censorship. Looking at their track record, it is easy to see how true this is: their plays are fiercely connected to their activism and to social issues. They are constantly making work to help promote change and discussion and their relationships with their audiences in Belarus and now worldwide, are very close. The company doesn’t just fight “state censorship” which they suffer in their own country, but also fight “self censorship” an illness they think is prevalent in the western democratic world, including the UK. This “self censorship” is even more dangerous than anything state imposed.

In Being Harold Pinter, BFT says “We claim our right to be offended.” I can’t think up a better placed or more courageous company than BFT to take up Harold Pinter’s mantle; they bear out Pinter’s last words in his acceptance speech perhaps more than most:

I believe that despite the enormous odds which exist, unflinching, unswerving, fierce intellectual determination, as citizens, to define the real truth of our lives and our societies is a crucial obligation which devolves upon us all. It is in fact mandatory. If such a determination is not embodied in our political vision we have no hope of restoring what is so nearly lost to us—the dignity of man.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here