The puppets that arrived in New York City in 1738 were certainly not the first here. Puppets had been created way before then by the Lenape people, who lived in the area for centuries; some of the tiny finger masks they made to represent the god of hunting, Misinghali'kun, in religious rituals still exist. And the Dutch had a tradition of puppetry dating back to the fourteenth century, so surely itinerant Dutch puppeteers existed in New Amsterdam, the colony that their countrymen established in 1624, four decades before the British took over the city and renamed it. But the first-known specific record of a puppet show in New York is an advertisement in the New-York Gazette newspaper, from February 1738, for The Adventures of Harlequin and Scaramouche, or The Spaniard Trick’d, to be performed at Mr. Holt’s Long Room for a ticket price of five shillings.

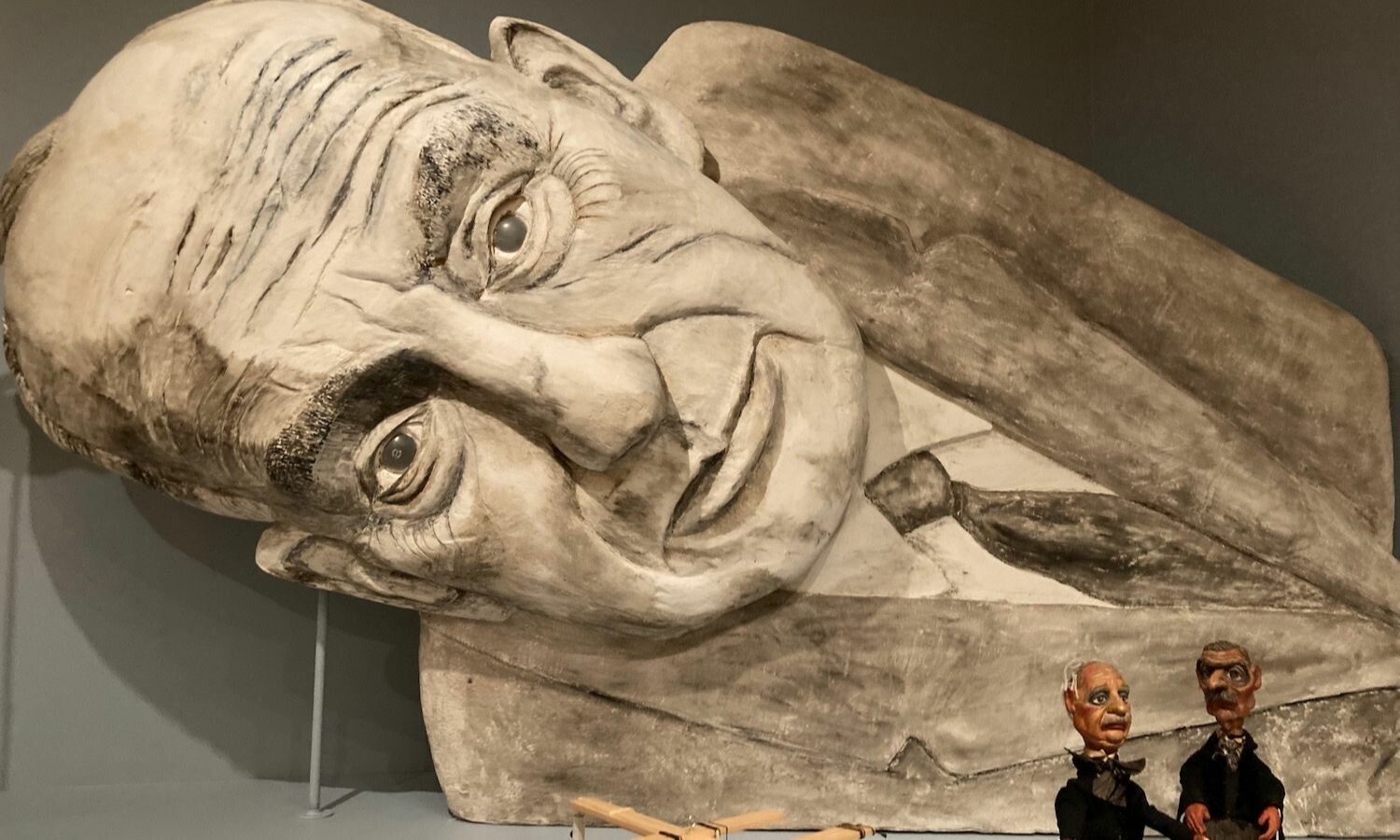

Both Harlequin and Scaramouche are characters in Punch and Judy, which is “probably one of the oldest continually performed puppetry traditions,” Monxo López explained to me, after he had shown me the exhibit of the Lenape finger mask and the reproduction of the Punch and Judy ad. Now he was pointing out different puppets, from Italy, Germany, Poland and France, each of which was a variation on the Punch character. They were among more than a hundred puppets on display in “Puppets of New York,” the exhibition López curated for the Museum of the City of New York, located in East Harlem.

“Almost every culture has developed their version of Punch”—a political puppet who “speaks truth to power,” López said. And nearly every culture’s puppetry, as his exhibition made clear, found its way to New York City.

“The Chinese were among the earliest here. There were the big dragons used in the Lunar New Year celebrations, and the small hand puppets from Chinese opera, and also Chinese shadow puppetry. Chinese shadow puppetry was here in New York City as early as 1799,” López said, pointing to a poster from that year for just such a show, called Ombres Chinoifes. (The title was in French, although the puppeteers were Chinese.)

López was giving me this tour on the first day of New York City’s first-ever official Puppet Week. Launched in August, it also featured another exhibition he curated, along with Leslee Asch, entitled Puppets of New York: Downtown at the Clemente, a look at the puppetry of a dozen living, avant-garde New York artists, which was taking place at the Clemente Soto Vélez Cultural and Educational Center on the Lower East Side. These and three other exhibitions were hooked to the second biannual International Puppet Fringe Festival of New York, also headquartered at the Clemente, offering three weeks of live in-person and virtual puppet performances from some dozen countries, as varied as Argentina and South Korea; India and Côte d’Ivoire.

“New York has for a long time been the global capital of puppetry,” said the festival’s artistic director, Manuel Morán. But even for New York, this was an unusually concentrated dose of puppetry.

Puppet Week offered something else as well. It encouraged a different way of looking at this ancient form of theatre and the lively, varied, often cutting-edge expressions of it that have been continually forged in this city of immigrants.

The press and the public ate it up. Here was a chance to revisit such beloved characters (all of which were on display) as Oscar the Grouch from Sesame Street, Trekkie Monster (a kind of Oscar alter ego) from Avenue Q, and Julie Taymor’s beasts from The Lion King, as well as earlier American TV favorites Howdy Doody and Lamb Chop; Shari Lewis’s daughter Mallory even performed with the feisty sock puppet both at the exhibitions and in the festival.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thanks for the heads up, Jonathan. I'll try and catch the virtual panel discussion live later today (I'm in Los Angeles) or in a re-broadcast if they post it archivally. The Puppet Fringe Festival looks beautifully inventive as so much of the great puppet work has always been. Thanks again!

Jonathan -- thank you, I loved reading this. The connection you make between the long presence of puppets in NY (and the US) and immigration is profound. Really enjoying thinking about this and reading about some of history of puppets in New York. There are first-rate puppet-makers around the country who continually remind us that theirs is a beautiful art form. Thanks again!

Thanks James. Puppetry is the one theatrical art form that I think makes the clearest connection between the local and the global. There's a panel discussion that touches on that topic tonight (August 31st) as part of the fringe festival -- http://puppetfringenyc.com/ta…