I have always thought of theatre people as the community that sustains and nourishes me, through school and university, and now in my life outside of formal education. It has always been life sustaining for me. So, when asked to curate a series on UK artists in the live art scene, I took it as an opportunity to eavesdrop on the intergenerational dialogues I wanted to hear, and to share them with others.

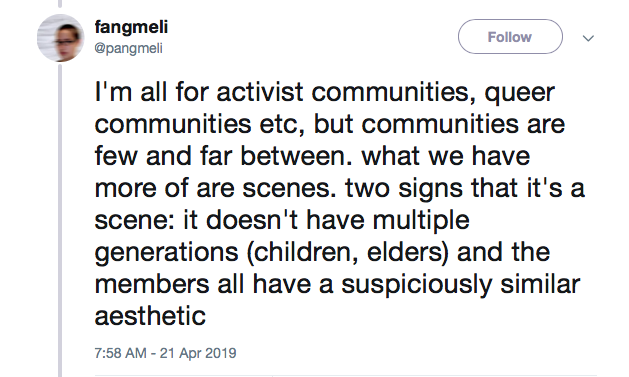

It is when different perspectives coalesce, when intergenerational knowledge is transferred across a group, that we are truly a community.

I reached out to six artists I love and respect—Tobi Kyeremateng, Joon Lynn Goh, Matilda Ibini, Malik Nashad Sharpe, Ava Wong Davies, and Demi Nandhra—and asked them to engage in dialogue with a collaborator from a different generation. I gave them no steer other than to use the space for a conversation they had been needing to have, and to have it with somebody they wanted to talk to. As the transcripts came in, I thought of Akasha Gloria Hull’s book Soul Talk: The New Spirituality of African American Women, where Hull speaks of the connection between political activism, creativity, and spirituality—how the three are intertwined in a deep way. I can see how, in each of the dialogues in this series, all three are present to varying degrees.

The urgency of political activism comes to the fore in Tobi Kyeremateng’s conversation with Roger Robinson. At twenty-four, Kyeremateng is already an award-winning cultural producer working across form, thinking about the black experience at every position of the theatre and what the generation below her will emerge into. In her conversation with Robinson, a poet with twenty-five years of experience, Robinson describes a series of collectives that came together to build new approaches to making work and to getting it seen in the eighties and nineties, which is juxtaposed with Kyeremateng’s articulated need for support systems now.

This push for the collective is also present in Joon Lynn Goh’s dialogue with Janna Graham. Goh, a cultural organizer and producer, has always had a certain clarity and rigor in her thinking about politics and organizing. This integrity shows in her choice to be in dialogue with practice-based researcher Graham, whose work has touched on social housing, workers’ rights, and support for those living with AIDS. Their conversation moves back and forth across the Atlantic and spans several types of practice: academic, community organizing, performance, and visual arts. The artists call into question the future of the institution and bravely ask that we make a new culture. Reading it reminded me of words from writer adrienne maree brown: “We are in an imagination battle.” This conversation is fighting to reimagine our futures from places of rigor, power, and possibility.

We, the marginalized, in all our shapes and forms, are always in the archive somewhere, we just have to be found, and this requires some work on our part.

The next three exchanges focus on the challenges of creativity. Malik Nashad Sharpe and Liza Johnson’s conversation is rich in cross pollination, with Liza speaking from her perspective as a film and TV director and Malik reflecting from their place in choreography and dance. There is a liquid quality to the conversation, which is heightened further knowing that, at one point their relationship, Malik was a student of Liza’s. It could be argued that performance art has a shorter lineage than other forms, but the strengths of that are apparent here: we are often only a couple of connections away from those who originated the form. The energy this can provide is present in their conversation.

Then there’s Ava Wong Davies, Maddy Costa, and Alice Birch’s conversation, the only one between three people: two critics, in Ava and Maddy, but also two playwrights, in Ava and Alice. It’s a reflexive and questioning conversation, one that situates critical writing both in the archive and in the making process, and asks probing and difficult questions about care, responsibility, and seeing the humanity in those who might encounter their words. Their writing is some of the most exciting and politicized coming out of London right now, and it’s very exciting to have them represented here.

The third dialogue that speaks to the challenges of creativity is between Matilda Ibini and Oladipo Agboluaje, two playwrights of Nigerian heritage working in a British context. There’s staying power displayed in their conversation, one of honing craft regardless of institutional support and potential familial disapproval. Their pre-existing relationship seeps through the words as they look at what has to be in place to sustain creativity: financial knowhow and people who kick up a fuss, opening the door and making sure it never closes.

Finally, the conversation between Demi Nandhra and Rajni Shah turns towards the spirit: the artist as a human within all of this, trying to find balance, growth, and healing in their work. Their dialogue is an intimate one, reflecting everything from institutional disappointment to the need for community. It holds contradictions, moments of intense recognition, and pockets of hope and agency.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here