Successful Marathon-Length Theatre

Sean Graney's Modern Dionysia

Not many theatre companies choose to perform anything that lasts more than a few hours. Audiences, even those with enough stamina for a four-hour show, may raise their noses at the idea of theatre that runs from sunup to sundown. So what makes All Our Tragic, a half-day spectacle involving all 32 remaining Greek tragedies, such a rewarding experience for so many people?

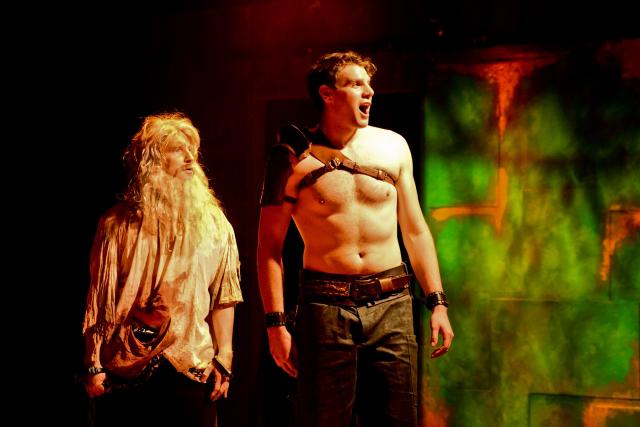

For Chicago’s The Hypocrites, it's all about the experience. This company's supersized performance takes the form of an immersive festival, one that's consistently called a “modern festival of Dionysus.” The experience includes food and breaks, and the atmosphere encourages discourse among those in attendance. None of this happened by accident. For years, one man worked diligently to cultivate the project.

Sean Graney adapted all these tragedies into one comprehensive script. He also directs the show and founded the small theatre company that produces it. To learn the story behind All Our Tragic, Graney and I met in an eclectic rehearsal and office space, a repurposed furniture factory used by The Hypocrites between performances.

In contemporary ways of watching Medea, we're missing the very social aspect of it, where we're able to discuss the finer points of the debate in the play. In contemporary society, debate isn't part of the experience of watching a play.

During our time together, I garnered a few hints about what makes this show such a success. The first clue came from the way Graney described modern presentations of the surviving Greek tragedies. I have transcribed and abridged his quotes for length.

Nowadays, when we go see Antigone or we go see a play like Medea, we show up at the theatre with our date. We get valet parking. We go to the lobby. We sit in the theatre. The lights go down. If we talk to our friend, we're shushed by the people around us. We can't open candy. We can't even bring drinks into the theatre. Medea kills her children, and we're like, ‘How are we supposed to feel about Medea?’ and then we leave and we're not allowed to talk. We just get in our cars and go and maybe get dinner with the same people that we went with, but we're missing a huge part of the experience of Medea.

In contemporary ways of watching Medea, we're missing the very social aspect of it: where we're allowed to talk about the play, where we're able to discuss the finer points of the debate in the play, where we're allowed to discuss what it means to be a stranger and how we should treat foreigners and, if we treat them badly, what happens. It's about what happens when men abuse women or manipulate women. These are just things that Euripides raises in Medea that we can't really talk about, while we're sitting in the theatre and the lights go down and the lights go up and we pick up our valet car and we go home. In contemporary society, debate isn't part of the experience of watching a play. I think that's sadly missing.

He makes a valid point. Modern Greek theatre shares little in common with the Great Dionysia, the festival dedicated to Dionysus that happened every year in ancient Athens. Those festivals brought together tragedians, actors, and large choruses to participate in a competitive performance that likely spanned around five days. At Dionysia, audiences did not quietly arrive with dates for late-evening performances. They spent the day at the festival. They ate and drank and talked.

Adapter/director Sean Graney's All Our Tragic uses the tragedies that were written for these festivals in an unexpected and surprisingly traditional way. He talks about the way the old festivals were set up and what it meant for the audiences to see multiple performances in a single day.

What else is sadly missing is that each year, each tragedian would write three tragedies and then they would write a satyr play. There are two things happening there. Basically, each tragedian is submitting a four-act play. Medea is actually an act, one act in a larger piece. When we're watching Medea, we're watching the third part of a longer piece that's meant to be in dialogue with each other. It could be very disparate plays, but they deal with the same themes and the same concepts and they sort of feed into each other.

Then there was a satyr play, which were these broad comedies about people with big phalluses knocking over vases and doing ridiculous things. So, comedy is a huge part of our understanding of these plays. It gives us time to digest. It gives us time to look at the seriousness of the tragedy. It allows us to pull back a little bit more and laugh at things in a way that's really helpful to dialogues. You go see a production of Medea now, and if you laugh at a production of Medea now, there's probably something wrong with you.

Audiences at the original festivals enjoyed tragedies written as part of a larger story, and modern performances omit this detail entirely. When Graney created All Our Tragic, he omitted specific satyr plays, but he kept the spirit. Throughout the performance, but especially during the earlier acts, the performers joke with the audiences, easing tension and encouraging discourse.

What I set out to do was create the festival, the atmosphere, the culture that was around ancient Athens for the time these plays were written. How do I transform our modern audiences to have a similar experience to what they had back in ancient Athens?

When he first started working on his adaptation, the script was about twice as long. He knew about the Great Dionysia, and he wanted to recreate it. According to Graney, the original concept included a three-day escape to the country. The audience would spend time away from their normal lives the same way the festivalgoers did in ancient times. It would start on a Friday night. Audiences would share dinner, drinks, and a show. I had heard a rumor about this idea before, and I told him that it all sounded exciting.

It's so exciting! In the morning, Saturday morning, you'd have breakfast, maybe some talks, you'd go on walks in the woods. Then in early afternoon you'd see a chunk and then there's dinner and discussion. Then, Saturday evening, there's another chunk. Then on Sunday afternoon there's another chunk, with all these other events happening throughout it.

The original concept gave way to a much tighter version, a performance that takes place in a single day. After the determination that a three-day festival would not allow for the wider audiences that he envisioned, Graney revised the piece with the help of the theatre community. He spent time workshopping the script and made additional revisions during his time as a fellow at Harvard's Radcliff Institute. He still makes small revisions, he says. He attends the show every week.

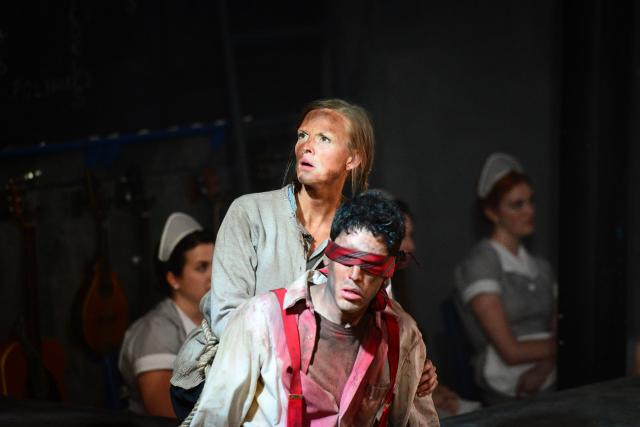

A few years before he started working on All Our Tragic, Graney tried his hand at a similar concept. He used all of Sophocles' existing tragedies to create Sophocles: Seven Sicknesses. In this early adaptation, he used a long-form style, tied together in the setting of a hospital, to integrate all of the material into a single show. It resulted in a five-hour performance.

There was a strong, heavy-handed theme in Seven Sicknesses. I noticed that all the Sophocles plays that survived touch on some kind of illness. I found that really interesting. That was a good metaphor for me to write and build a production around. It ended up being a little too heavy-handed. As I approached All Our Tragic, I was trying to think, ‘Is there a metaphor, is there a metaphor like sicknesses that can expand all 32 of these plays?’ and there really wasn't. I found myself trying to shoehorn some stuff in there, but it wasn't working, so I let it go.

Theatre-lovers connect with All Our Tragic because this type of performance connects with its source material in a way few other performances do. This show, which could more aptly be referred to as a one-day festival, uses the same techniques that made those in ancient Athens such remarkable experiences. Graney's desire to encourage discourse and his focus on relevant social issues mimics those used in the time when Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles wrote them. Even the parts he alters nod to the spirit of the original festivals.

It was always my goal that I was not just making a play, I was making this experience, this festival for people.

Graney does not keep every custom. In ancient Athens, only men performed in the shows. While some women may have been allowed into the audiences, the number would have been minimal.

The Greeks had a democracy, but it was a definitely a flawed democracy. It was such a great advent in human culture to be like, ‘Hey! We shouldn't be clan leaders. The people should have a voice.’ Granted, they were only a select group of people, so it was flawed and there's many things you could criticize ancient Athens about, but the fact that they took that leap was huge.

So, how do we create that now? While I was constructing the piece, it was always my goal that I was not just making a play, I was making this experience, this festival for people. So as I was building it, that was always engrained in the workshop and the writing of it: How do I accomplish making this event?

With a year for the first draft and an additional three for revisions, he created the show we see today. The themes of the tragedies remained intact, a preference toward local or national laws remains a matter of heated discussion even in modern times, and he included many modern references. One character carries a comic book in his back pocket. Another carries a teddy bear. Many of the actors perform in modern attire. Graney sustains the spirit of the original festivals even with these alterations. They match a practice from the original festivals. The ancient tragedians often included direct, localized references specifically for the local audience on the day of the performance.

Every part of the show, from the choice of food to the duration of the breaks, comes from a focus on audience engagement. Graney noted that it would seem unsettling to serve meat at an event that so effectively promotes compassion, so the company serves only vegetarian dishes. They do not, however, prevent anyone from bringing their own food, and Graney jokes that some audience members bring their own beef jerky.

Graney's time developing the original eighteen-hour adaptation, his fellowship at the Radcliff Institute, and his earlier Seven Sicknesses provided the experience he needed to create something that very few other theatre companies could pull off. The Hypocrites benefits from all of this, and the resulting show supports the spirit of the original festivals. All Our Tragic invites audiences to participate, along with the rest of their community, in a modern Festival of Dionysus.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I really love the concept of reverting back to the traditional style of presenting plays; the concept of theater as a social art form has always been present (even in modern productions) but the ideology of immersive experiences as a way to facilitate the reactions and interpretations in theater is something that is lacking in many pieces. Although I feel this style has the possibility to greatly impact the general view of performances, I'm curious what the effects may be on tickets sales etc.

Obviously if an audience becomes a part of the experience it is a worthwhile endeavor; but the concept of all day pieces can be intimidating and alienating to those just beginning their interest in the theater. With many regional and community theaters struggling to meet their running costs, there seems to be a financial implication and risk with these types of work that could discourage their viability in the industry.

Absolutely. When we think about traditional theater, specifically ancient Greek tragedies, it's important to remember that society placed a completely different value on the theater of the time. In some cases, governments could even reimburse citizens who could not otherwise afford to attend a festival. That does not happen today.

If we want to spur the same kind of debate (or inspire the same kind of multi-day festivals) that they had back then, we're going to need to consider new methods.

Graney grasps this concept well. His eyes light up when he discusses the old festivals of Dionysus, and he alters his productions based on the feedback of a much larger theater community. When we chatted, he told me that he had to work diligently to shorten All Our Tragic into a single-day event after producers told him that it could not work as a three-day festival.

This type of responsive coordination between writers, directors and producers seems to be a necessity for those companies who want to create immersive, festival-style productions.