On Supporting Both Theatre J and Mosaic Theater

A Perspective from a Regional Jewish Artistic Director

Several days ago I made a donation to Theatre J, and also to the new Mosaic Theater founded by Ari Roth. Supporting one theatre does not mean I cannot support the other, and I indeed hope those audience members who say they will not return to Theatre J will reconsider, based on the art presented.

As the producing artistic director of the non-profit, independent Jewish Theatre Or (or is the Hebrew word for light) in Denver, working collaboratively with a Jewish arts center located in a JCC venue, we produce American premieres of Israeli plays and festivals of staged readings. I need permission for any play I wish to produce in one of the venue’s theatres, be it Israeli or not. I have been turned down on issues far less controversial than the conflict. The level of Ari’s institutional support for doing Jewish theatre is greater than anywhere else in the country, but regional Jewish artistic directors face the same pressures when choosing to produce Israeli plays. The DC JCC has been a model of support for Jewish theatre that many of us would welcome outside of DC. We need their vision locally. How else can we preserve and pass on our rich theatrical heritage?

It is imperative that Jewish theatremakers who support Ari in his new endeavor also support Theatre J. It is a vibrant, important Jewish institution that has been inspirational to all of us. Theatre J, the DC community, and all Jewish theatre artists are still reeling from his unfortunate departure. However, I am saddened to think that artists are leaving in protest and saddling the staff with even more responsibility and stress during this difficult transition. I urge all my Jewish theatre colleagues to help Theatre J weather the storm and to support Theatre J as well as Ari. We are all in this together.

With two theatres, there will be even more opportunities to tell exceptional stories with more jobs for deserving artists. There is no worse way to pay tribute to Ari’s accomplishments than for the theatre he led to flounder. Mosaic’s just published mission looks exciting, with a promise of further diversity in programming. However, there are a myriad of wonderful existing plays and new voices that have yet to be heard that can be the basis of wonderful seasons yet to come at Theatre J. It is possible for Theatre J to retain its stature and in fact widen its audience. It is ironic that Ari’s termination is doing more to create dialogue in the Jewish community than any one production ever could. It is painful, but from pain comes growth.

It is ironic that Ari’s termination is doing more to create dialogue in the Jewish community than any one production ever could. It is painful, but from pain comes growth.

By supporting two theatres producing provocative plays, we’re also supporting expanded opportunities for dialogue, which will ultimately benefit the community. The issue of how to use theatre to create dialogue is at the heart of this current crisis. I have struggled with this problem ever since producing our first Voices Festival of Israeli plays ten years ago in Durham, North Carolina. I don’t have the answers, but I have a lot of questions. We bandy about the importance of this dialogue, but what do we really mean? For any given play, but particularly for an Israeli political play, what is the nature of the dialogue we wish to have? What are the dialogue’s goals? With whom is it supposed to occur? How many people does it involve, what are their ages, and how do we structure the conversation that accompanies the performance? What are the criteria for success?

In Israel, thousands, even hundreds of thousands of people might see a given play—Israelis have an enviable culture of going to the theatre. My attention was riveted when I first learned that 500,000 Israelis had seen a play entitled Women’s Minyan. What play was such a large percentage of worldwide Jewry seeing that was completely unknown to American Jews? So I produced it and others, not because I wished to present a particular point of view, but because I didn’t know what to make of all these unique stories I was reading, and I needed the community to help evaluate if any of these plays should become part of our cultural heritage, to be passed down to future generations along with Fiddler on the Roof. I was also amazed to learn that it is possible in Israel for a play to stimulate widespread discussion among its citizens, perhaps enough to affect policy.

Is that the hope for producing a political Israeli play in our country, or is the goal more modest? Is it so we can reflect better on our own identities and reexamine our Jewish values? Is it to educate us about the complexity of life in Israel that no one can really understand without spending time there? Do we intend to purposely draw a wider intercultural audience to help address the problems the play presents? Are non-political Israeli plays just as important?

Do we need multiple Voices festivals throughout the country? A national day when theatres read plays empathetic to both Israelis and Palestinians? Perhaps it’s enough just to help an audience or two process the action that has transpired. Maybe affording a few with short-term catharsis is all we can expect. Or do we really want a call to action? Do we need the press to expand the discussion?

What if there are people with whom we’d like to engage in dialogue, but instead we are alienating them? If we choose a play that criticizes Israel, how do we also give voice to those with differing points of view so they are not left out of the discussion and do not label the play (or individual curating) anti-Israel? Must every full production with one point of view be paired with a full production with another? Panel discussions and lectures on Israel tend to draw audience members inclined to agree with the opinions of the sponsors, or those who attend are predisposed to being open to new views in the first place. Even with theatre as the prism for reflection, do we still run the risk of preaching to the choir? If people are fearful of plays they suspect are critical about Israel, how do we address that fear so they can experience the magic of theatre and not feel that public discussion is threatening? Do we write them off as partners in dialogue or look for other means to engage them? Americans are not as used to political plays, and also not as used to going to the theatre as Israelis are. If acknowledging the narrative and pain of the other is part of a necessary reconciliation process (which I am unqualified to define), is it possible that both Israelis and Palestinians can be viewed as the other? Do their respective pains need to be acknowledged equally on American stages?

Can we demonstrate that discussion itself is a strength in Jewish values, and that the broader the discussion, the brighter that Israel’s light unto the nations will shine?

Let theatre of reconciliation address the reconciliation process within our own Jewish (theatre) community. Both Theatre J and Mosaic will move forward, and let us together define a process of dialogue that will engage a wider audience, not only in DC, but throughout our country.

***

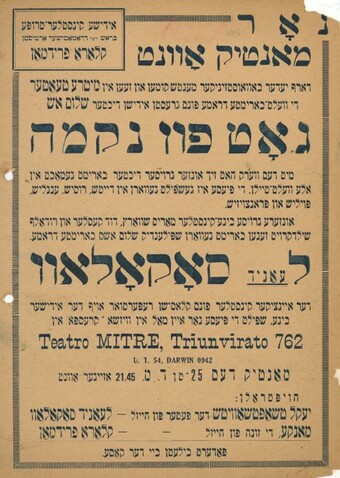

Photos from Productions at Theatre Or (or is the Hebrew word for light)

Photo 1: Albert Banker, Megan Hatch, and Carol Bloom in Savyon Liebrecht’s Apples from the Desert. Photo by Sarah Roshan.

Photo 2: Jeffrey Blair Cornell and Diane Gilboa in Motti Lerner’s Hard Love. Photo by Sheldon Becker.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Diane I applaud your interest in bringing a wide range of excellent Israeli plays to American audiences. I am involved here in Israel with a few translation projects. The desire is very mutual to bridge Israelis and Americans through theatre.

You stress the importance of dialogue. I agree. But I don't see evidence (yet) that the DCJCC is willing to engage in full and open dialogue; it appears that certain subjects, and viewpoints, are to be considered out-of-bounds. That's their privilege -- just as it's mine to opt out of such a narrowly-restricted "dialogue." Unfortunately, several issues have become conflated: how the DCJCC dealt with a "problem employee" brought things to a head, but how the organization has recoiled from work that probes sensitive, important issues drives to the heart of what dialogue is even to be permitted. As a child of the '60s in America, I resisted the "my country, love it or leave it" rhetoric that designated any dissent from "official" narrative as disloyal or unpatriotic. Questioning "received truth" is a fundamental function of the theater; it's one of the things that makes theater so vital. Yes, it's transgressive. It's uncomfortable. But it's how a society learns about itself. Some may shy away from truly open dialogue -- it's their option, so be it. I'd like to stick with Theater J; I have no doubt they will continue to make some good theater... within limits. But Theater J has to toe the line imposed by their the host institution. If I believe in the importance of dialogue, as I do, then I have a problem. They've made it clear they don't want to engage with me -- and that's when I exercise my option, namely to vote with my feet.

Your call is to support a theater that won't allow for the complexity of addressing Israel's occupation of Palestine. I would no more be interested in supporting a theater that only did plays in which x group is villainous and y group is heroic. It isn't promoting dialogue to present one aspect of a political equation. And it's whitewashing a current climate of devastating inequity. When JCC's can make advancements toward a free Palestine, and an Israel accessible to non-Jewish people, then I'll be able to celebrate those theaters with a clean conscience.

I have certainly have criticized the cancelation of the Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival which is ultimately what led to the firing of Ari Roth from Theater J -- and even noted that a discussion of the complexities Arab-Israeli conflict in general and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in particular is one that Israeli dramatists have wanted to have. However, the notion that a Jewish theater (or really, any Jewish cultural institution) must make this the main focus of their programing, when the Jewish people have, amongst other things, a continuous literary tradition (and all the accompanying controversies) that predates European civilization, is absurd: There are many compelling themes and topics for Jewish theater to tell.

The Voices From a Changing Middle East Festival did not come to an end -- instead, it has a new home at Mosaic, and judging from Roth's past programing, the programing will likely not be exclusively (or even primarily) about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict -- though it will undoubtedly be addressed. A case in point: the photographs used to illustrate the article are from productions of Savyon Liebrecht's Apples From the Desert and Motti Lerner's Hard Love which are both about the schisms between Haredi Orthodox Jewish communities and secular Israeli society.

Now, given the dedication to Jewish culture in general, and Jewish theater in particular that both Roth and Gilboa share, it seems quite normal to embrace diversity -- in terms of both discussion and in programing, So supporting both theaters is eminently reasonable from that point of view: Jewish theater is not, and cannot be limited to just a few themes or to the repercussions of a single historical event in the 20th century.

http://artsfuse.org/120628/...

I cannot wait to see how Ari Roth brings his curatorial gifts to the Atlas on H Street (you can read his insightful explanation of his vision and values here: http://dcmetrotheaterarts.c.... And I fully expect to continue to see thrillingly good productions at Theater J on 16th Street (my five-star review of the current show, Aaron Posner's "Life Sucks," is here: http://dcmetrotheaterarts.c.... The way I see it, having both Theater J and Mosaic Theater Company in town means one thing and one thing only: more great theater.