Nate Cohen: It's been ten years since you wrote The Gun Show. What led you to start writing it when you did?

Ellen Lewis: For ten years after my husband died, I didn’t talk about his death. I didn’t even talk about his life, actually. I’d found my way into the Los Angeles theatre world, and most folks I met didn’t even know I’d ever been married. I don’t fault myself for this sin of omission. Not much anyway. My silence on the subject of my husband was a defense mechanism. Something ruptured inside me when he died, and it took a decade before I was ready to start knitting myself back together. I was strong enough, then, I guess, to open the box of memory and darkness, and see if I could make something of it.

Nate: There’s such a profound necessity there.

I remember being really struck when I read the play the first time about how vulnerable and present it felt. How does it feel to have now had hundreds of artists poke around inside this hugely complex and challenging part of your life?

Ellen: It’s been… not such an easy thing. Playwrights have to be just as vulnerable in their work as actors, but usually not so publicly! We get to hide in our garrets when we’re spilling our guts out onto the page.

But there is no hiding in The Gun Show. From the very beginning, I understood that my job in any production of the play was to remain absolutely open to the actor who was telling the story and to sit in my assigned chair with the rest of the audience as they figured out that the story that was being told belonged to me.

Universally, the actors and directors who have chosen to do The Gun Show and invited me to be part of the process have been tremendously kind. They’d picked this play about guns and loss for a reason. They’d said yes to it, frequently, because they had their own experiences with guns and loss. We all shared our stories, and their willingness to meet my stories with their own helped me be braver about the whole thing.

I also drank a little.

I feel a lot of love and gratitude toward all the artists who went there with me, to those dark places. We held each other’s hands.

I guess that what’s changed in my relationship with the show is me.

Nate: How has your relationship to the show changed over the last ten years?

Ellen: I wrote the play when I was living in New Jersey, with the support of my little Passage Theatre playwriting group. It was really frightening to write. Thank goodness for my fellow playwrights (always!). It’s easier to be bold when you feel safe

The first productions were pretty intense. We didn’t know what to expect. You know? What the audience's reactions would be. The play is a little raw, and a little punchy, and a little close to home for almost everyone who sees it. I don’t think there’s a single person in America who doesn’t have a personal experience with guns.

In the very first production in Chicago at 16th Street Theater, directed by Kevin Christopher Fox, we worked together to craft a conversation with the audience that followed the show, inviting them to share their gun stories, in the wake of me sharing mine. And they did!

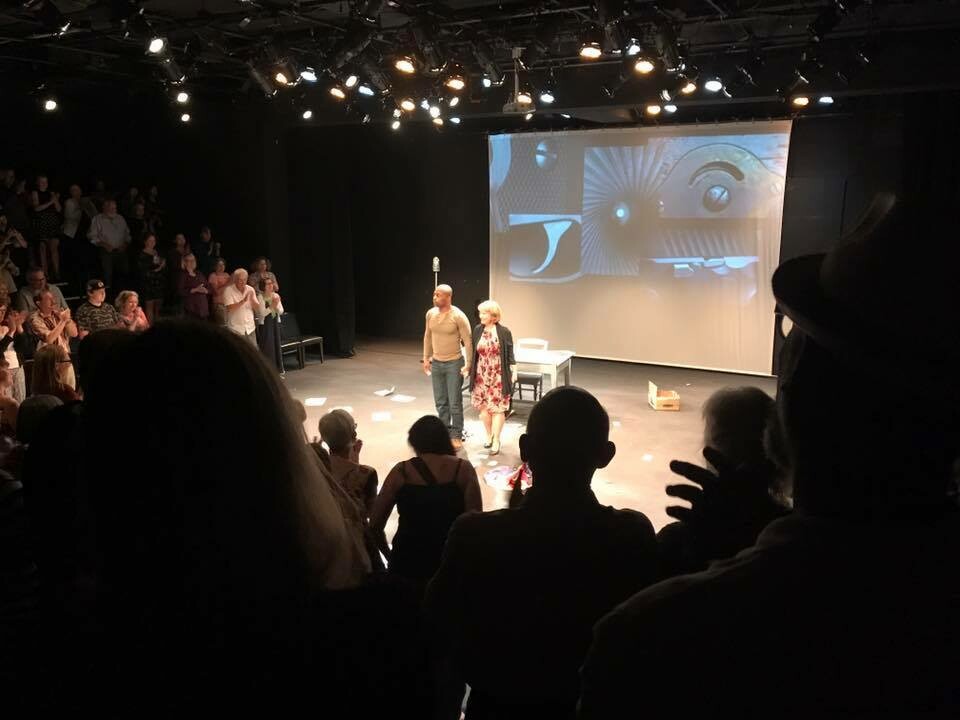

The play has had more than fifty productions over the last decade. I’ve been part of at least half of those, sitting there and waiting for the actor telling my story to point his flashlight at me, and say those words: “...and when I say my story, I mean hers.” It didn’t really get easier to be part of those productions of the play—open myself up to the intimacy of working with a new actor and a new audience. Being present. Being absolutely present. And open. Not hiding. Not anymore.

I guess that what’s changed in my relationship with the show is me. I wrote it because I needed to write it. I wrote myself into it because, I guess, I somehow knew that the writing alone wasn’t going to do the trick—give me that gift of transformation that I yearned for, though perhaps I didn’t know if I deserved. And it worked. I’m here, my whole, messy, honest self, on the other side of hundreds of performances. I’m not doing the duo version as often anymore. Maybe… maybe I’m ready to let it go

Nate: I love all that. Watching you watch the play was always the most fascinating part of it to me. When we were working on it for close to a year and a half, it was really powerful to see how your engagement with it changed. For the first week or two of our initial run in Portland, I remember feeling very protective of you. Shawn and I talked about both wanting to be there because we had the impulse that we wanted to be able to stop the show at some point if it was going a certain way. By the time we were touring in Europe, it felt like you were sharing the emotions out instead of fighting them off.

What the play does, which I continue to believe in and feel is necessary, is reject mindless, simplistic, binary side-taking in favor of thoughtfulness, complexity, storytelling, story listening, and embracing the fact that we’re all in this together.

Ellen: I’m grateful for your protectiveness, even if you never had to fight anyone for me.

No one ever has come after me for talking plainly about guns. We had a guy in West Virginia who shared that he had his gun on him at the post-show conversation, which TJ Young, our moderator, took in stride with remarkable aplomb. I remember a couple coming up to me one night and telling me I hadn’t changed their minds one bit, and they were keeping their guns. A few folks—in different cities, different productions—told me that my husband would have found another way to kill himself if he didn’t have a gun. That… hurt.

But what happened much more frequently was someone putting their arms around me and telling me about the person they’d lost to gun violence—suicides and accidents and murders. I’ll never forget the woman sitting beside me during the show in Chicago one night, who reached over and took my hand during the fifth story.

What the play does, which I continue to believe in and feel is necessary, is reject mindless, simplistic, binary side-taking in favor of thoughtfulness, complexity, storytelling, story listening, and embracing the fact that we’re all in this together. That seems more urgent than ever.

Nate: This was something my students brought up. A lot of them felt really uncomfortable in a good way, in the way I think the play is trying to achieve, with some of the “pro-gun” talking points. I hesitate to call them that, since I think a huge and fundamental purpose of the show is to move past the binary of “pro-gun, anti-gun”, but the talking points that stem from the “pro-gun” side of the political spectrum. One of them talked about the fact that she had grown up in New York City, had never seen a gun in her life, and didn’t know anyone who owned one. The girl sitting right next to her, who was a friend of hers, said, “Oh, my dad has six,” and she was totally shocked.

This was something I know I struggled with hugely in my own relationship to the piece. I have pretty strong feelings about gun violence in the United States and have done a substantial amount of activism work around gun control, so having to sit with this play was something that took some concentrated effort on my part.

As part of our original production in Portland, we collected “Gun Stories” from people in our community. One that really affected me was something a carpenter (John) at Artists Rep in Portland told us. He’d grown up on a farm in rural Idaho (I think it was Idaho?), and he and his younger sister had to walk almost a mile to get to the main road to catch the bus to school. One winter when he was ten or eleven years old, his parents started noticing cougar tracks in the snow in the mornings following him and his sister out to the main road. This is a part of the world where cougars are a major safety concern, and a hungry full-grown cougar could absolutely attack and take down a couple of elementary school kids. But because of their work schedules, his parents weren’t in a position to walk him and his sister to the bus stop every morning, so they called the school. The solution they came up with was for him (John) to carry a shotgun with him as they walked out to the bus. When they got to the bus he would hand it off to the bus driver, who would in turn give it to the vice principal to lock up in his office during the day. When they got back off the bus at the end of the school day the bus driver would give him back the shotgun, and he’d carry it across his chest as he and his sister walked back up the road to their homestead.

This story blew my mind. It was so far removed from my own lived experience growing up in the vast urban sprawl around Chicago that I sort of didn’t know what to do with it.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here