The Hungarian company continued to be active in Cluj between the First World War and the Second World War, but in much more precarious conditions due to lack of financial aid from the Romanian state (during the first years after the war) and the inadequacies of the summer theatre building, in which the troupe had to move after 1918, and which had no central heating. Janovics spent the entire wealth he had gathered (especially from filmmaking) to make the living and working conditions of his actors bearable. The Romanian company also encountered hardships: the funding was deficient because Romania had suffered huge losses in the war, the audience was scarce in Cluj, and the actors had to be brought from the other provinces and not all of them adapted to the conditions.

During the years between the two wars, the repertoire of the Romanian company of Cluj was dominated by French plays (especially Molière) and by national plays, and the playwright most often put on stage was Ion Luca Caragiale, the tutelary personality of Romanian theatre. Lucian Blaga, the most important Romanian writer, philosopher, and playwright born in Transylvania, who came to be known after the Second World War, hardly found a place on the stage of the Romanian stage in Cluj until the 1929–30 season. However, at the invitation of Janovics, Blaga’s first play, Zamolxis, premiered in 1921 by the Hungarian company (directed by Janovics himself). At the time, the Hungarian company and their audience were more open to dramatic experiments, given their longer and richer theatrical tradition.

The Opening of the Conservatory and the Second World War

In 1920, the Conservatory of Music and Dramatic Art opened in Cluj, led by the Romanian composer Gheorghe Dima. Later, in 1931, it was promoted to the ranks of the higher education institutions, and its name changed to the Academy of Music and Dramatic Art. In 1940, during the Second World War, both the Academy and the (Romanian) National Theatre were evacuated and temporarily moved to Timișoara, because Cluj and a part of Transylvania had become part of Hungary again. The Hungarian company once again occupied the grand theatre downtown, until the end of the war in 1945, when Cluj and Northern Transylvania were reincorporated in Romania (under Soviet occupation).

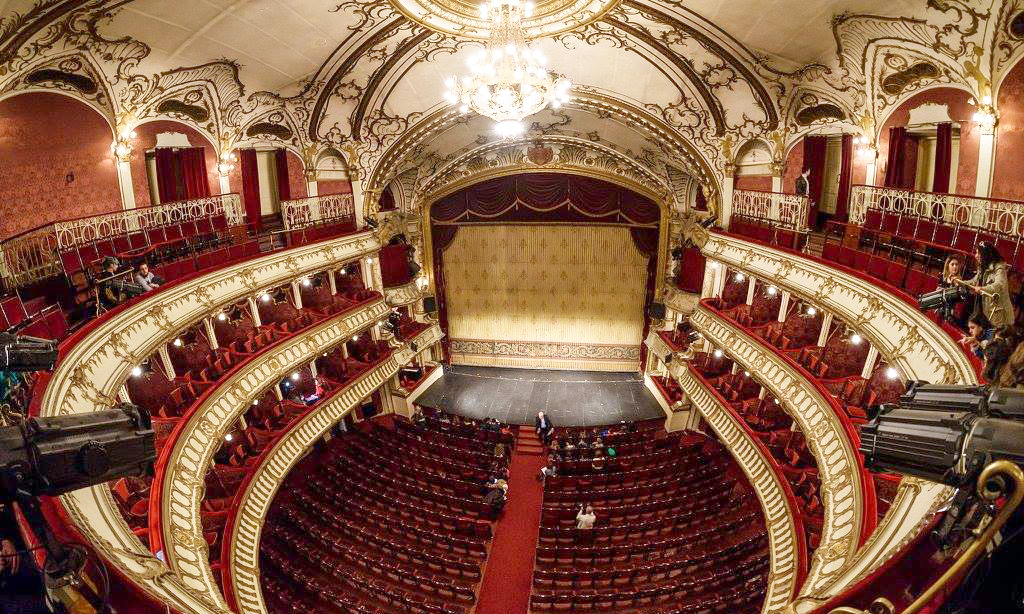

The Romanian company returned from Timișoara and retook its place in the grand theatre, where it continues to reside, and the Hungarian moved back into the theatre on the bank of Someș. Both buildings underwent important changes in the following years, the former being extended and the latter enhanced, between 1959 and 1961, with a post-Stalinist classicist lounge. After 1990, several studio halls were added.

In 1946, the communist authorities established the Hungarian Conservatory of Music and Dramatic Art of Cluj, in addition to the Romanian one, which had been established in between the two world wars. In 1948, the two education institutions were renamed Institutes of Art and, in 1950, they were joined together as the Szentgyörgyi István Theatre Institute, with courses in Romanian and Hungarian. In 1954, however, the theatrical education of Cluj was dismantled by the transfer of the departments to Bucharest and Târgu-Mureș—resumed only after the fall of the communist regime.

Transylvanian Romanians were frequently prohibited from erecting a national theatre and setting in motion a professional theatrical movement.

From the Communist Era to Today

The communist era in Romania was marked by struggles of artists to bypass censorship. Several names of theatre directors who worked in Cluj during this time stand out: Ștefan Braborescu, Radu Stanca, Vlad Mugur, György Harag, Alexa Visarion, Aureliu Manea, Dan Micu, Alexandru Tatos, Victor Ioan Frunză, Alexandru Dabija, Tompa Gábor, and Mihai Măniuțiu. Some of these directors fled into exile after years of confrontations with political pressures, among them Mugur and Andrei Șerban. Several of them were lucky enough to see the fall of the communist dictatorship in 1989 and were able to return to Romania and resume their activity, fully enjoying the freedom of art. Since then, for example, Mugur and Șerban have both staged many memorable and important productions at the Lucian Blaga National Theatre and the Hungarian State Theatre.

The creation of the first few independent theatrical companies after 1989 opened a new chapter in the vibrant and complex theatrical life of Cluj. Their emergence was stimulated by the resumption of theatrical university education in the city. Some of these companies, like Teatrul Imposibil (the Impossible Theatre), founded in 2003, had a short-lived life, due to lack of funds. Yet Teatrul Imposibil made a mark through its programs meant to promote contemporary playrights and reading-performances or shows that were staged in unconventional spaces (courts, bars, rented premises). Under its tutelage, theatre books and a magazine were edited and a festival was even held, which had an international focus at the beginning, but which then had to limit itself to the national stage.

The year 1998 saw the opening of an independent art and cultural centre, named Tranzit House, in a former synagogue close to the city centre. To this day it hosts all sorts of exhibitions, concerts, and performances. Beginning in 2009 until last year, Fabrica de Pensule (the former brush factory of the city) was an important cultural centre that hosted and co-produced visual art exhibitions and independent theatre and dance productions, a theatre festival, and all sorts of debates. It was dismantled due to disagreements between its founding members, who decided to separate and look for a fresh start elsewhere.

In 2010, the first independent Hungarian acting company from Cluj was founded, under the name of Váróterem Projekt (Waiting Room Project). Some of its performances, which are usually in Hungarian, are addressed to Romanian audiences as well. Reactor de creație și experiment (Reactor of creation and experiment) is currently the most active independent theatre in Cluj. Founded in 2014, it focuses on young audiences and has developed programs, such as artistic residencies, aimed at encouraging young performers, directors, and playrights. It also organizes workshops, performances, and other activities for children.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here