Scene Two: Joining a Global Community

If you had told us in January 2020 that we were about to become part of a global community of creators and actors, we would have thought you were lying. It started with a seven-hour binge-watch of three versions of a single show, The Art of Facing Fear. These productions were created by a coalition of artists from Africa, Europe, the United States, and South America, all led by Brazil’s Os Satyros. Each production had fingerprints from the regions they came from and the artists that created it.

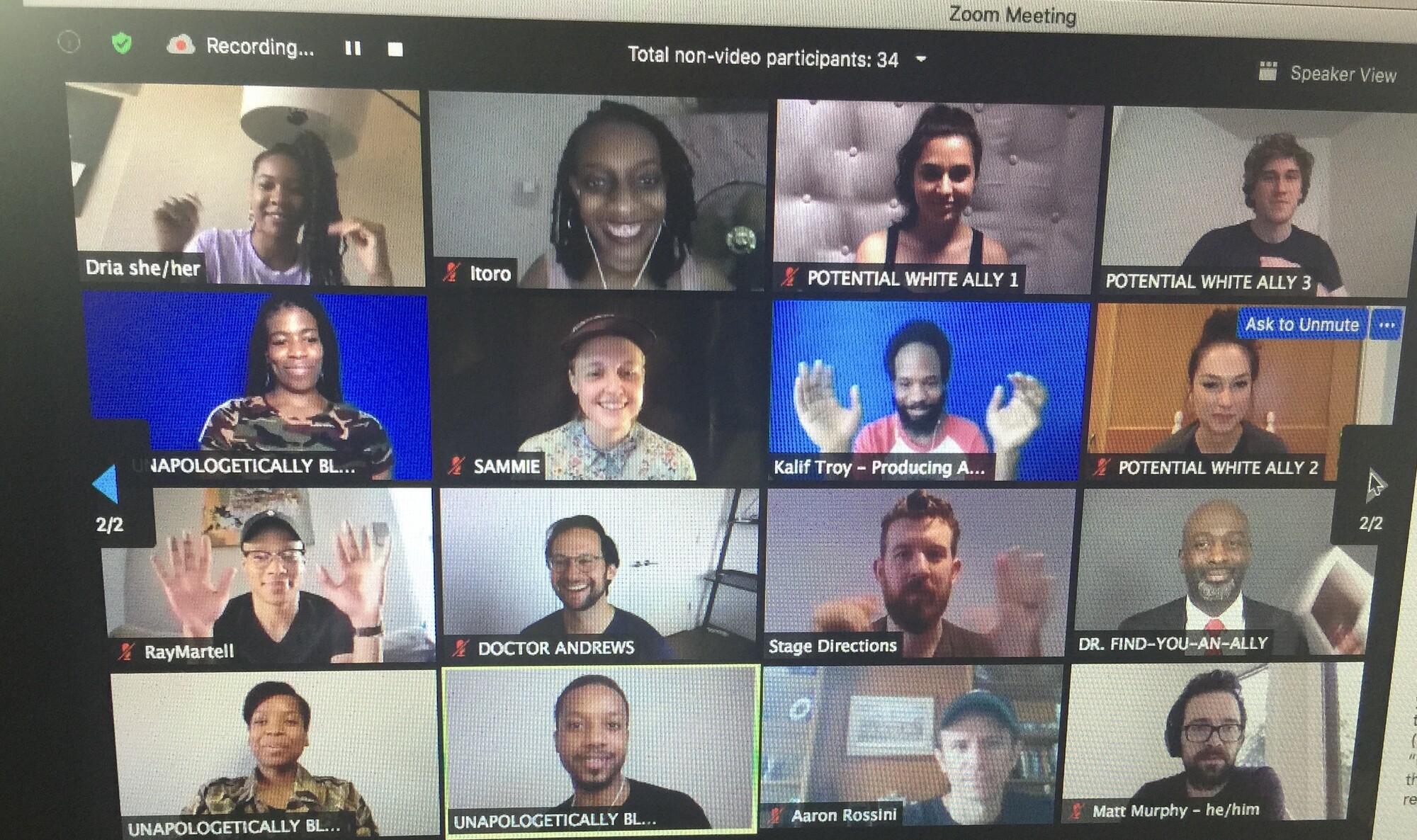

On Zoom, we talked with the production team. They shamed us with only three words: “It’s more democratic.” While theatre artists in the United States were arguing about aesthetics and egos, the international community had zeroed in on the real issue: a theatre that can be made with the devices in the creators’ hands is a more democratic theatre.

The Art of Facing Fear led to more reviews for more productions. We felt more than a connection with Os Satyros; it was a bond built from having a common mission. We all want to create a global family based on collaboration and democracy. We all want to amplify the work of the individual. We have never hugged or shared a meal with these people, yet we count them as family.

Digital theatre launched this group of artists—and hundreds like them—into a national arena where they could be seen by a wider audience.

Scene Three: Finding Little-Known Writers

We rarely knew any of the artists that we reviewed before the pandemic, which could not be illustrated better than through our experience with Tabitha Chasse’s A Pirate Christmas Carol, presented by Frank Sanchez Musicals. When theatre moved to digital platforms, Frank Sanchez Musicals—a company based on Long Island, New York—created a broader network that would not have been possible before the pandemic. One of the organizers of the show left a comment in a digital theatre Facebook group, which is how Dana found it. We are Christmas Carol devotees and have seen just about every adaptation out there, so we were sold immediately.

This Zoom play had some of the best design and performances we had seen that year. Tabitha had written the most streamlined adaptation that synthesized everything pirate and everything Dickens perfectly. She would later tell us that this was her first play, but we were so certain that she was a seasoned professional who we should have known about before. The real story was one that we had seen ever since we started reviewing: a group of local theatermakers putting out high-quality work in relative obscurity. Digital theatre launched this group of artists—and hundreds like them—into a national arena where they could be seen by a wider audience.

There are more of us who see what digital theatre can do, what it’s doing now, and what it will do in the future. Digital theatre needs to be good, it needs to be understood, and it needs to be accessible to everyone.

Act Three: What Now?

Scene One: The Return of In-Person

We had mixed emotions when we joined hundreds of digital audience members to watch Mike Daisey at Frigid NYC. First, there was a feeling of triumph because it was the first hybrid—meaning it was viewable in-person and digitally—show for Frigid. Second, Daisey’s piece harnessed all the pent-up emotions we had after the tumultuous election. Third, we couldn’t help but fear that this was both the beginning and the end.

Every time we have seen advances and setbacks in the fight against the virus, we have had to deal with the real possibility that everyone would turn off their screens and flood right back into theatres. Then, our sources for reviews—not to mention all the artists that we have been calling the core cadre of digital theatremakers this whole time—would exit the game. There would be no way for us to start attending every event we were invited to in person. With every twist and turn of the COVID pandemic, we have no clue what's on the other side. The one thing we are afraid of is everything going back to the status quo. We should have known better.

Scene Two: Looking Ahead

An award show we pitched as a joke in 2019 became a full production a year later, with a team of screen managers from Combined Artform on a livestreaming setup lent to us by Frigid New York. For the first time, we saw all the creators we reviewed come together to honor the work that everyone had done over the year. We hosted the show, and hundreds of people on five continents attended. Afterward, the two of us were numb for an entire week.

We found that there are more of us who see what digital theatre can do, what it’s doing now, and what it will do in the future. Digital theatre needs to be good, it needs to be understood, and it needs to be accessible to everyone. We always thought that if we weren’t talking about this then nobody was. Once we reached two hundred reviews, we needed a rest. We were tired, and we had never given ourselves permission to take a break. We know now that we’re not leading from the front, and we want to help build a unified community that has a bright future.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here