Where Possibility Abounds

a 20th Anniversary Conversation with the 1995 Cohort of Jerome Fellows

This year, the Jerome Foundation is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary— the indomitable Cindy Gehrig came to the Foundation forty years ago and, during her tenure, the Playwrights’ Center has facilitated Jerome Fellowships, which are the longest fellowships that the Foundation has had in their history. Arguably, the Jerome Fellowship is what truly launched the Center from “a collection of writers hanging out and reading work together,” and moved it towards a place where playwrights could get support in myriad ways, including stipends.

Jeremy Cohen: When P. Carl created HowlRound, he invited a handful of us to talk about what the focus of the articles would be, and one of the things that Daniel brought up was the idea of bringing back together a really strong class of Jerome Fellows to see how they’d spread across the field. And here we are.

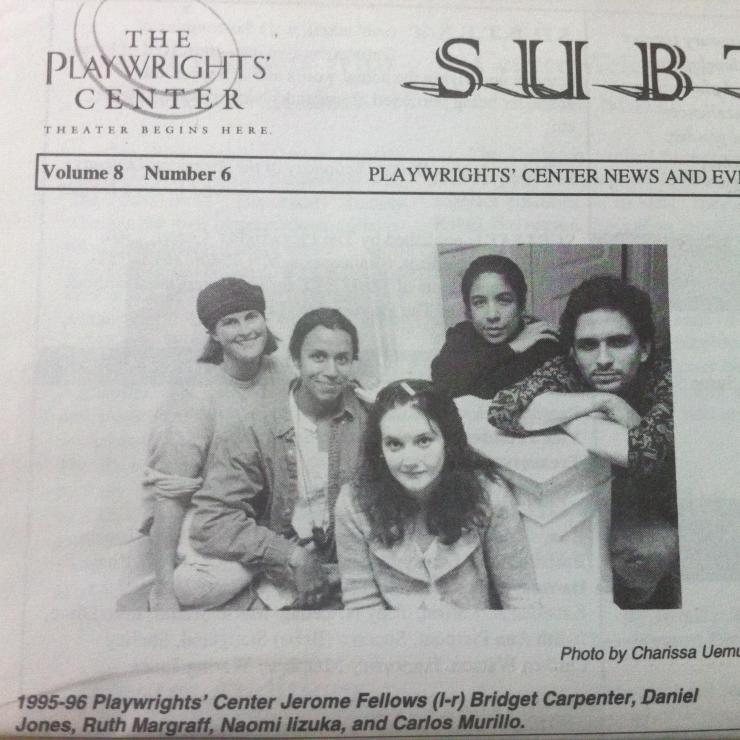

It was the fall of 1995 when you came together originally, and for the first time in twenty years, we’ve gathered for this conversation a reunion of stunning cohorts: Bridget Carpenter, Naomi Iizuka, Daniel Alexander Jones, Ruth Margraff, and Carlos Murillo—with Elissa Adams as the brilliant Lab Director of the Center at the time.

What’s exciting about your class is that you’ve all had these really amazing, radically different artistic and career trajectories. Honestly, it seems bizarre that you were all together in one building and it somehow didn’t explode with not only what you were creating then, but also with the potential of what you were about to become.

Elissa, looking back you obviously experienced a number of different writers while you were in your tenure at the Center. What specifically marks for you—individually and as a group—how this set of writers is defined?

Elissa Adams: What stands out clearly is that this class of Fellows filled the Playwrights’ Center with a sudden influx of writers in a single year who were bringing a strong interest in experimenting with form and with language, which had not been as strongly part of the aesthetic DNA of the Center up to that point. How that happened is wonderfully alchemical and one of those great moments of chance in the arts—when these five extraordinary artists came together.

Jeremy: Do you all remember thinking at a certain point in the year, “there’s something really happening here that feels different from where I just came,” or that you were discovering a different way of approaching writing and theatremaking than you had previously found?

Carlos Murillo: Honestly, I felt a sort of hero-worship. Before the Jerome, I worked in the literary office at the Public Theater, so I had read all of these writers’ plays and thought they were the coolest writers writing at that particular time. So there was a little bit of anxiety because I had so much respect for all of them, but it became such a strong community. The fact that everybody was pushing boundaries in their own unique way was really inspiring. It lit the fire under us all to see how far we could go as artists.

Ruth Margraff: Before going to Minneapolis, Brown University was instrumental in Bridget, Daniel, and my lives because we had a place where we could experiment in and discover our authentic process. Austin became another place that Daniel and I met up again, and then some of us met up again at New Dramatists. There were stations along the way, but the Playwrights’ Center and the way Elissa led us to think that anything was possible, changed everything. And I don’t know if that ever really happened again with that amount of time and space.

I remember working on an installation piece at Red Eye Theater, and they just turned over a key to me so I could go in anytime I wanted to make work. There was another time when I got really destitute and Elissa let me get a check early, so I felt like I had an artistic home. Because the winters are so long, it felt like it went on years.

(laughter abounds)

And it kind of did, though, because we all kept coming back. It felt like we could return. Even to this day, I still read for the Center and am an Affiliated Writer—I can stay in the orbit of the PWC, and I think that’s wonderful.

The fact that everybody was pushing boundaries in their own unique way was really inspiring. It lit the fire under us all to see how far we could go as artists.

Jeremy: When we started the Affiliated Writers Program last year, it was our way to figure out how to take forward that spirit you’re talking about and say, “Keep coming back to us. Let us know what you need and let us try to figure out how to help you in different kinds of ways,” rather than solely being a fellowship-year only home.

Daniel Alexander Jones: I felt a tremendous recognition from the very beginning that I was in a special moment with artists who were completely ready for the opportunity that was available to them. Elissa was completely ready to have a conversation that really went to the bone. We hear so often in the field about what can’t happen and why it can’t happen. The overwhelming atmosphere of that year was not only that it can happen, but also it will happen, and it will happen with rigor and with a kind of excellence of spirit. I remember specifically the ways in which everybody was supportive of one another. Carlos made me a mixtape of David Bowie to introduce me to his music and talk about structure and performance theory and persona.

Ruth: Hey! Carlos, you introduced me to David Bowie, too!

Daniel: Ruth, you were so immersed in your language when you were working on Gat Him To His Place and I learned about how sound can tell story on its own. What I remember most about you Naomi is your precision. There was a reading of Skin, and it upped my game in terms of thinking about how spare and precise I could be with language and with gesture. The moment Bridget and I sat down next to each other we became best friends. We would sit and read plays out loud to each other over tea in that frigid winter, talking about structure and why we loved certain writers. And Elissa kept us all in conversation about what our core questions were over our year there. She reminded us and nudged us towards more sophisticated experiences of those questions. It was pretty powerful. The actors involved in our workshops got so excited about the aesthetic shift that was happening as well. These brilliant performers got to come in and do work that they rarely got to do, but had a real desire to do.

Bridget: It was so heartening because with all of us being together, there was room. I don’t think of myself as being a boundary-pushing artist, but I loved being around those people. I remember thinking that we were all so radically different from one another and yet there was plenty of room for us all in the theatre. There was enough pie for everyone, and we can all take a piece. I felt so inspired by that and thrilled! We really felt like each other’s brothers and sisters. We each had our own team, but we were all on each other’s teams too. This culture was absolutely spearheaded by Elissa who is not only an extraordinary artist, but also a great curator. I didn’t come to Minneapolis thinking that I would have time to be in a bigger conversation; I thought I would be here for a while and write some plays for grad school. But that became a byproduct—it was much more about the time that we all spent together and much less about the number of plays that I churned out.

Naomi Iizuka: Elissa had a sixth sense about how to create a space where so much writing and thinking could happen. We could fully be ourselves, and at the same time, be influenced by one another. In very real terms, she created the conditions for a kind of chemistry where each one of us transformed. It was critical that we spent a lot of time with one another. We heard and saw each other’s work, but maybe the most important thing was that we had a lot of conversations with one another about everything under the sun. I have vivid memories of talking late into the night with Carlos at the CC Club, and with Bridget at the pool hall where she worked part-time, and with Ruth at this polka bar that we used to go to, and of walking down Lyndale Avenue with Daniel. talking and laughing, being quite literally breathless, and being blown away by how his mind worked.

Jeremy: Was there a moment during that year that felt like you were hitting a wall and then, something enlightening or transformational emerged? What challenging moment has played out in different ways on your path?

Ruth: Elissa, the way you would stand in front of a large group of people was inspiring. To this day I try to have that sort of poise. It was like learning how to be.

Bridget Carpenter: And remember I taught you how to drive a stick shift, Ruthie? You bought a truck and you didn’t know how to drive it.

Ruth Margraff: Yes, of course!

(laughter)

Bridget: We learned how to be in the world together. There’s something so comforting about reflecting in one another’s growth—we’re all learning as we go along anyway. Learning that there isn’t a blueprint.

Carlos: Each encounter that I had with every one of the writers in this group pushed me in ways that I think have had long term influence. And Elissa modeled the idea that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all way of working and there shouldn’t be a preconceived notion of what a play or performance should look like. It was a model of dealing with each of us on our own idiosyncratic terms, but at the same time, pushing us to be more of who we were as writers, and extending ourselves beyond who we thought we were as writers. It’s one of the values that I bring into the classroom as a teacher—dealing with young artists who are just starting out and feeling their way through finding their voices. Rather than try to impose some kind of external ideal, I find ways of helping them carve out their own path. Yeah, that was a really huge influence over the course of the last twenty years.

Ruth: And thinking about how to develop those plays in a correlatively idiosyncratic manner. Elissa’s dramaturgy was specific to each world of each play, and from play to play. We all learned to participate in that dramaturgy together; we developed our own way of looking at dramaturgy within each world. If we had learned a cookie-cutter dramaturgy, all the plays would have ended up looking alike, which happens in the field too often, unfortunately.

We learned how to be in the world together. There’s something so comforting about reflecting in one another’s growth—we’re all learning as we go along anyway. Learning that there isn’t a blueprint.

Daniel: As a group, we wrote our country. We wrote the worlds that we lived in: our United States of America, and our world at-large. We also found speculative worlds that involved science fiction and dreamscapes that felt like the future we were born to. They were very personal and reflected vantage points, specific to each writer and their own journey. When I think about the aggregate of the work that happened during that year, I reflect on the impact that it had in our community. I think all of us had really compelling conversations on how to move that work forward with every artistic director in the Twin Cities.

And you asked where the tension is for us, Jeremy. For me, it’s been very interesting as an artist twenty years into my career to look back. I’ve heard so often what can’t be onstage and why can’t audiences get it, which is why risk is reduced. That year reminds me that it actually happened and that people responded to the work. This crisis of diversity that we have around gender parity, and racial, ethnic, and cultural representation is as old as dirt, and we’ve encountered it. The way we dealt with it then was to make this work, which made the world we wanted.

Elissa: To me, it seemed so...obvious that this was an amazing group of diverse and extraordinary voices who represented what the future of American theatre should and would be. But when you all began to go off into the world, your paths were often harder than I had expected them to be. I thought, “How is it not clear to everyone else in the American theatre the extraordinariness of these voices? These are the artists we need to listen to!” Now, eventually, you all found your way and have made a real impact on the theatre landscape, but I got so caught up in the richness and excitement of that Jerome year and the quality and power of the work each of you created that year, I just expected that you would be welcomed and embraced unequivocally. Naive, perhaps…but driven by my belief in what a remarkable group you were.

Naomi: It was definitely a world filled with possibility that created a kind of artistic freedom, which is very rare. It really felt like whatever you wrote, however you wrote, and whatever the work looked like, it would be seen and heard on its own terms. Elissa saw our work and she spoke to us about it—she had faith in us, while provoking and challenging us. Looking around at Bridget, Ruth, Daniel, and Carlos, I’ve also been emboldened by their boldness.

Carlos: Elissa assembled an incredibly diverse group of writers—in terms of background, culture and aesthetics—yet it was so effortless. No hemming and hawing about it, or worrying and twirling your mustache in the corner wondering how to please an audience. The Center’s leadership didn’t put obstacles in front of us like: “This is what a season should look like. This is what our world looks like so…write that.” Twenty years later, our field is still having those conversations and I want to smash my head against a wall because it seems like everyone’s creating powerful work and it’s more difficult than it should be. The Playwrights’ Center certainly has remained one of the antidotes to that way of thinking. But once we all departed Minneapolis, it was a very difficult reawakening.

As a group, we wrote our country. We wrote the worlds that we lived in: our United States of America, and our world at-large.

Jeremy: Can you talk more about those challenges you’ve faced in the field? How do you reckon that within yourselves and with what you’ve come up against in different phases of your career?

Daniel: Many of us left for communities where there were many other playwrights who reflected these aesthetic or procedural ways of thinking about work. Ruth and I did a lot of work in Austin, Bridget went to LA, and Carlos came back to New York. So, it felt like there was a generational uprising of new work and new voices. One of the things that my own journey brought me into contact with was structural resistance, which, in that horrifying way, locates both in larger institutional conversations and also in individuals within those institutions who resist change. New work often has a different language. If you don’t speak that language, it means that you have to either learn it or accept that there are people in your house that speak a different language than you.

Ruth: It’s interesting to look at the institutional model of development that regional theatres and Broadway and performing arts centers ran—and the RAT (radical alternative) theatres were disappearing because they were burgeoning at the end of the '90s when the funding changed. The RAT theatres were the ones doing Mac Wellman and Erik Ehn’s work, and they would do some of my work. There was BACA Downtown, which Bonnie Metzgar ran for a while, where folks like Mac, Suzan-Lori Parks, Laurie Carlos, and Erik came through. I would never have predicted that we’d all end up in universities.

(laughter abounds)

At times I thought the university was the last patron of the arts; at times it’s been my refuge and strength; and at times it’s also been just another corporation. But I think it’s interesting (and a bit shocking) that most of us ended up leading playwriting programs in very different institutional academies. It tells me that our ideas were too big and bold, but our students will parse out little bits of that, and that will enter the field. We need people like us teaching the next generation, but we may not be honored in the way where we get many productions. It’s like Mac and Erik, who I still feel need more honor in terms of productions. They’ve mentored thousands of artists into a new generation.

Bridget: It’s definitely a validation of our voices that you guys have taken on a leadership mantle. Nobody went to sleep at night as a kid saying, “I can’t wait to lead a playwriting program.” Right? But I actually think that’s a huge thing. Because I didn’t go to sleep at night saying, “I’m going to write a TV program,” either. So I think there is a kind of deepening about continually asking how you are going to tell your story, your life story. I think everyone went to sleep and woke up dreaming, “What’s the way that I’m going to etch it out?” You can’t predict the specificity of it, but it speaks to a voice and ideal that is large and forward that you need to pass on, and that’s a mission that goes with it. To me, what you’re describing is the Paula Vogel story too. A lifetime in academia, but her drive was always: I need to write these stories.

Carlos: And of course there’s a sense also of, “What’s the aspiration?” We make this stuff that most people don’t really want. But we believe in it, and it reaches whomever it reaches. In the classroom, what we can bring to the table is the sense that career is important, but it’s not the whole thing. There’s something powerful about tapping into the individual vein of truth, story, or language. Each of us as writers reach beyond ourselves because we share a core belief in what theatre potentially could do if people go along with it. Sometimes I go back and forth, you know. Am I a snake oil salesman to my students because I’m trying to sell the idea of “capital T theatre?” The field doesn’t have a lot of room for “capital T theatre,” but at the same time, seeing transformation and having the ability to see beyond one’s own limited personal property allows you to extend beyond your own reality.

Daniel: Playing a little bit of the devil’s advocate—or the angel’s advocate: with Fun Home and Hamilton, we suddenly have structures that more closely resemble the structures we were playing with than the structures in the mainstream when we were writing. It’s about persistence. It’s not only about the theatre, but also our society, and our culture. The winnowing down and narrowing of representation, language, and the caging definitions of what it means to be a person are things that concerned us then and still concern us even more as adults. Some of us have families, and some of us consider our mentees, or our students as family. So, I feel there is still an urgent need to continue to embody, represent, and teach the ways that are not limiting. They are limited only by choice and not by capacity. One thing I remember from our Jerome year was how many conversations I had with people who said they didn’t like experimental theatre, but really loved the work that we were all doing.

All: Right, right.

Daniel: Inherent in all our work, whether it’s experimental in structure or not, is a pedagogical aspect. Carlos and Ruth, you taught us how to hear your plays in your plays. And Bridget, you taught us about the underbelly of so many of the familiar relationships that we thought we knew so well; you found a way to turn it and reveal something else. And Naomi, you taught us about the collision of mythos, history, and the future; to have a character as an archetype and a street-corner kid at the same moment. I think it’s about the worth of being an artist who puts story into the world that is both complicated and accessible.

Naomi: If I stop to think about it, it makes sense that many of us are now at universities running MFA programs. At its best, a university is a place where you’re working from a spirit of inquiry and you’re embracing experimentation. I’m at UC San Diego now where the sciences are huge. When we talk about what we do in theatre to our colleagues in the sciences, we talk about how the theatre spaces we work in are like laboratories. We talk about how experimentation is at the core of what we’re doing in theatre. I find that way of thinking genuinely liberating. There’s a strange way in which those of us at universities are replicating this extraordinary world that Elissa built for us during our Jerome year—the focus was always on the work in whatever shape it took.

Ruth: I never got the sense from you, Elissa, that you would participate in a hierarchy of: “This play can move here," or, "this play will never move there.” But I think to continue to hear those caging ideas of "where this play can go" is so limiting and demoralizing. I didn’t know until after the fellowship that I should stop using the word “experimental” and try hard not to describe my work that way. There are many labels that can so quickly become tracks that you never get off, and it deadens the work

Carlos: I mean, here we are twenty years later and we’re all still alive, and—

(laughter)

Bridget: Kudos! Wow, we’re really setting the bar low. That’s all we had to do?

Carlos: But there’s something incredibly comforting to know that when I pull up my Facebook, I see you all doing your thing. It’s quite bolstering to me in those dark times we all have as artists. Here’s a crew of people that I knew twenty years ago who are still on their feet and haven’t lost the plot, or haven’t strayed away from who they are as artists. For me that’s a huge, huge gift.

What’s crucial is finding that balance between being open to the world and the various paths that open up to you. Be alert enough to see those paths, and brave enough to take them, while at the same time, tend to the core of who you are as a writer.

Jeremy: At the Center twenty years later, we’re trying to ask a lot of these same questions, especially seeing that there are large swaths of the institutional side of theatre that are focused on the buildings and how it all operates—and very little about the care of the artists. What a privilege to go to work every day and focus on the individual artist. Which, of course, keeps the bar really high, to ensure we’re always meeting each playwright where they are and how they are on any given day. And to really be challenging them to say: not only are you the artistic director of your time here, but also you need to ask for what you want. Not just what you need, but what you want. So, thinking outward. What do you feel like you’ve learned since—given the spirit of twenty years ago and everything you’ve learned since?

Bridget: Ruthie, I love what you’re saying about the unpredictability of it all. I felt like in this family of playwrights I learned to be my true self. And I learned to be a playwright in the world. What I couldn’t have predicted was that I actually also wanted to be other things, which is why I started writing other things. If you’d asked me, “Are you going to start writing television or film?” I would have said “No” because that was definitely not how I defined myself. And in a way it’s still not how I define myself—not because I don’t love it, because I do, but I came to it later. I came to it already fully formed as a playwright and somebody who was ready to use my voice in a different way. I would say that everything I ever learned I could boil down to: I like being a beginner. I like learning new things. That’s how my storytelling has evolved. That’s the part of the process that I really like, and I didn’t know that twenty years ago. I just knew I had some stories that I wanted to tell and explore.

I would say to any young playwright: be kind to yourself, and be open to what you want to keep coming. Because I think the younger me would have felt guilty and not a pure artist if I said I was going to write television or film. And now I write anything, and I love every part of it. And that’s because I got this time in paradise at the Playwrights’ Center to forge my voice.

Daniel: There’s so much out here to eat, to taste, to feel, and to keep that spirit of openness always is key. In thinking about emerging writers, and this generation of writers and theatre makers that I’m encountering, they’ve got it! There’s a consciousness emerging—a tidal shift. So the thing that I would offer from twenty years ago is that little glimmer, like a compass in the very core of who you are that guides you toward making, guiding you towards other people that you meet that feel like artistic family. This glimmer guides you toward people that might scare you a little bit, but you feel like you have to go talk to them because you’re going to learn something. Really guard that with your life. It’s your compass. The world will tell you “no” a million times, and unless you keep that alive, you can’t tell yourself “yes.”

And there’s a necessity in carrying your work to term, bringing it into the world. That may come through a submission, or it may come through a relationship with an institution. As a writer, learn how to produce your work. Learn how to have different versions of the work. Have a performance piece, have a book, have a TV show, and have a web series.

Bridget: Pivot.

Daniel: For damn sure! Because if you keep smashing up against the same wall, time and time again, nothing’s going to happen. I wouldn’t have a career twenty years later if I hadn’t dug down and made a number of the things myself that ended up being pivotal. No one gave me permission to do it. It led me to moments where I had a recognition, or connection with other artists. But in those in-between times, when it’s not coming from the outside, go back to that compass and then be willing to do that work. Keep the glow.

Ruth: It’s funny where that compass takes you, you know.

Naomi: Yes! You have to be able to adapt. What’s crucial is finding that balance between being open to the world and the various paths that open up to you. Be alert enough to see those paths, and brave enough to take them, while at the same time, tend to the core of who you are as a writer. I think the trick is how you do that. I always come back to the idea of having a tribe, or a family of artists that push you, and inspire you—they’re the people that you come home to. Like Daniel said, I’m a big believer in making things happen and not waiting for permission. It comes back to that sense of possibility that Elissa instilled in us in that year. It’s not so much about circumventing theatre institutions, but seeing all the compelling examples of work that have sprung up and thrived outside the familiar institutional models. I tell my students that it’s an incredibly exciting time to be a playwright. Whether they’re writing for theatre or writing for a TV show, this is an historical moment where possibility abounds.

Carlos: I think back on who I was twenty years ago and how narrow your blinders can be in terms of what you think the trajectory of your life is going to become. I didn’t think very much about being married, having kids, or leaving New York. There are so many things that I tied myself to, but when you’re young, it can be hard to see that life is quite large and unexpected. Things happen to you, you encounter people, and situations that take you on all kinds of exciting turns. I’ve learned you can build a life that’s actually very large and inclusive of so much. My art is very, very important to me, but so are the two children that I’ve raised, my family, and the work that I do with my students. Each aspect of your life informs other aspects of your life: your family changes your perceptions about art, and the art changes your perceptions of your family. So, a deeply complex life is possible, and it isn’t limited by choosing a path that doesn’t provide so many material rewards.

All: Hear, hear!

The Playwrights’ Center Jerome Fellowships are awarded annually, providing emerging American playwrights with funds and services to aid them in the development of their craft. Four $18,000 fellowships will be awarded for 2016-17, in addition to $1,750 in development support. Fellows spend a year-long residency in Minnesota and have access to Playwrights' Center opportunities, including workshops with professional directors, dramaturgs, and actors. The final application deadline for the 2016-17 Jerome Fellowships is Thursday, November 19. Please visit www.pwcenter.org/programs or email [email protected] for more information.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Such a beautiful article and such a testament of the time. Congratulations to all of these vital and essential artists, each one a hero.

I loved reading this -- what a great celebration of five wonderful writers and Elissa supporting them with grace and future. Thanks for putting this together.