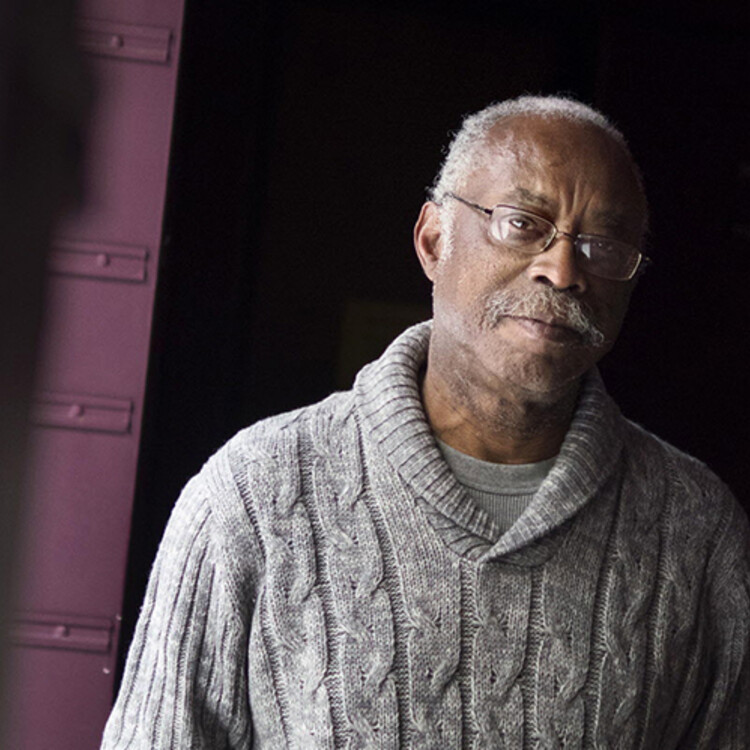

Playwright Carlyle Brown and director Noel Raymond have been collaborating in their respective roles for nearly thirty years. Now, they are exploring working together as co-creators of a theatrical work in which they will both perform. Something new is about to begin.

Carlyle Brown: You've always been the interpreter of my work, the director, and I've always been the guy who created the thing. Now we want to do something different, which is making something together.

Noel Raymond: Yes. We're both finding it difficult to find a place to start. The way that we would generally be working together is a path we know. We're trying to find a whole new path.

Carlyle: I have my own way of working alone until the script turns over to you, and then we work together in a different way. But now we're talking about the two of us co-creating something, so we've been hashing through stuff. I didn't think we would get as emotional about it as we did.

The idea is to find a series of little truths about friendship that explore its mystery and magic.

Noel: My impetus for trying to make something with you is just the longevity and the depth of our relationship, both as collaborating artists and as friends, ultimately. There's something to be mined in that. I don't know what that is, and not being a writer, I don't know where to start. But I have this instinct and impulse that there's a story there.

Carlyle: I am not comfortable with the idea of a story being about our friendship because that already exists. I'm suggesting that we use ourselves as a context and start our story from there.

Noel: Totally, and I think we've wandered around the block a few times and found maybe a way into a story that both uses our history and our actual relationship, but busts it open a little bit, too.

Carlyle: And the core of the thing is friendship.

Noel: Friendship!

The idea is to find a series of little truths about friendship that explore its mystery and magic. They might come from our own lives and our own experiences, or they might come from a completely abstract notion of what friendship is. We can put these together in a way that is surprising and beautiful and invites people into the conversation.

Carlyle: And then there’s an opportunity to show the opposite: what friendship is not.

Noel: Part of it, too, is that I feel like I'm a different person than I would've been if I hadn't been your collaborator and friend. Who I am is not defined by it, but completely shaped by our long history of working together and being in each other's lives.

It's, in some ways, kind of improbable. In 1994, I was invited to read a role in your play Masks of Othello when you were a visiting artist at Penumbra Theatre in St. Paul, Minnesota, and your play, Buffalo Hair was on the stage. So, you invited me after that experience to come see Buffalo Hair, which I did. Then we went and hung out afterwards and had this great conversation about theatre and art, which was really inspiring to me at that time, just out of grad school. I don't even know what the next step was after that, but somehow, I ended up in your kitchen talking to you about your play The Negro of Peter the Great.

I was newly out of school, and I was like, "Why would he want my opinion?" This is this famous playwright who's doing all this stuff...

I mean, that's what matters most in the theatre: hit people where they live, the internal thing.

Carlyle: I didn't think I was famous then.

Noel: I've been telling you—

Carlyle: I don't think I'm famous now.

Noel: I've been telling you for thirty years, you're famous. I think you could accept that at this point.

Carlyle: Yeah, maybe at this point. But back then it wouldn't give me two wooden nickels to rub together. It didn't mean anything.

Noel: Well, to me you were accomplished. You were a working playwright. You had a show on a stage at a professional theatre. You were brought in from somewhere else. You were exploring all kinds of interesting ideas. So, I felt really flattered to be invited into a conversation.

Carlyle: Well, you always had something interesting to say, something from the heart. I mean, that's what matters most in the theatre: hit people where they live, the internal thing. When we work together, the whole thing about the character is the internal workings of the character.

Noel: In my mind, our friendship skips many years ahead until I'm working at Pillsbury House, and you did—

Carlyle: Talking Masks.

Noel: Talking Masks with Louise Smith. Then we did lots of work on Are you now or have you ever been... which was just so wonderful. It was very artistically satisfying.

Carlyle: Well, not always for the actor though, because it was—

Noel: It's a lot of work. Yeah.

Carlyle: It's a lot of work.

And looking at the script, sometimes you just don't really see it. The Langston Hughes character has got to type and do all these other things, and the typing has to coordinate with the screen that is displaying the poem in text form.

Noel: But that was so fun, the first time at PlayLabs in Minneapolis when the filmmaker came and helped make the words live as a character in the play.

Carlyle: That kind of thing was a risk, and you were just so open to that kind of weird idea.

Noel: I love weird ideas.

Carlyle: And you don't say no right away. It's like, “Let's try it. Let's see.”

Noel: The only thing you're ever going to make if you don't try something new is something you already made before.

Carlyle: Boring.

Noel: That's one of the reasons I love theatre. It gives you an opportunity to step into the unknown in community with a group of other artists and try some stuff.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here