Where Thou Art

PortLAND

In this series, Joan documents a year-long research project in which she travels across the United States, exploring the different ways in which communities use the arts to address trauma.

The concept of “home” is a basic human right, but more and more I find that it’s regarded as a luxury. I often think about what that word means as I’m spending this year traveling across the United States essentially without one for the New Works Research Project (NWRP). However, I still say, “I’m headed home” when driving back to the house I’m living in while in Portland, Oregon, and I “went home” for the holidays. “Home” is my high school theatre room in Woodland Hills, California, as well as my aunt’s house in Spring Lake, New Jersey. It’s a privilege that I can refer to four different places with one word while many struggle to keep one. Since the beginning of time, people have been driven from their homes, and today we’re certainly not unfamiliar with these headlines.

The goal of the NWRP is to discover ways in which we, as a society, can better use the arts to heal communities in distress. I’ll be mapping the efforts that cities already have in place while investigating new ways in which they hope to creatively process and recover from trauma.

The city of Portland doesn’t necessarily appear to be outwardly struggling. So when I announced that I was starting the NWRP here, the question arose: “Is there trauma in Portland? What’s the cause of distress?”

Land. A large portion of the population of Portland struggles with the ownership of land. While temporarily living here, I witnessed three manifestations of this.

The goal of the NWRP is to discover ways in which we, as a society, can better use the arts to heal communities in distress.

The Original LAND

On my seventh day in Portland, I attended a “Conversation Series” hosted by the MFA students of the Art and Social Practice program at Portland State University. I sat with the eight students in a circle at the back of the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art and listened to Judy Bluehorse Skelton talk about land. I learned how the federal government uses very specific language to describe reservations and native programs, intentionally avoiding phrases like “trauma recovery.” There’s nothing like changing or eliminating language to project the same desired effect on a controversial era in American history.

“All humans suffer that trauma when you have to leave the land you’re from, where your ancestors are buried,” Skelton said. It was almost as if preceding and pained voices spoke through her. Forced exile is a dramatic trauma exclusive to no single time, place, or culture—she called on her heritage, the plight of the Jews, and the exodus of Syrian refugees today. It isn’t new information that survivors pass on their traumas; recent studies even show that the DNA of second generation trauma survivors is affected. From Judy’s talk, it was clear that both the land and people suffered a devastating colonization.

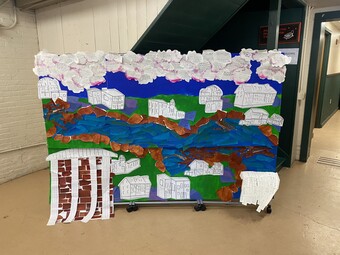

Judy recalled the tribes who lived in Oregon before colonization and how European farming practices disrupted vermin control, land management practices, and flow of wetlands operations. What spoke to me was her recent social efforts to reconnect the people to the land. She facilitated the restoration of an old potato farm—now Quamash Prairie—in order to regenerate camas, a first food and source of carbohydrates for Indigenous people. In addition to regenerating the land, the project has a deliberate emphasis on relationship-building. Quamash Prairie now serves as a place for elders to share their stories “in a way that they’ve never shared” with a younger generation. For the outlying community, hopefully these efforts will increase cultural awareness, serve as an example for the relationship-building that lies ahead, and create truly sustainable and regenerative communities.

PortLAND

In 2013, Oregon was the number one destination among people who moved from one state to another, according to CNN. With the cost of living of half that of Los Angeles, lush scenery, and hip culture, Portland is a desirable place to live. However, the boost in population has driven up low housing prices, slashed job availability, and steadily increased traffic and commute times. Although almost everyone I’ve met in Portland has been kind, friendly, and willing to engage in conversations with me—even after learning that I’m from Los Angeles—in most interactions I start off explaining, almost apologetically, that I was only in Portland temporarily. Baristas and bartenders talk about the invasion of outsiders. Many Californian developers are buying up land, demolishing gorgeous historical buildings, and building high-rent housing, which means some lifelong residents feel they are being forced out.

Urban exile, commonly and casually referred to as gentrification, is occurring in Portland, and it’s similar to what’s been happening in San Francisco. Unique cultural aspects draw people to these cities, but start to slip away as more people claim them as their own. Portland is notoriously an artisanal town, but as it hits its saturation point, it almost becomes a caricature of itself. Battle lines in both cities are being drawn along economic and cultural lines.

In the midst of the housing emergency in Portland, I’m thinking about Quamash Prairie, and envisioning how the NWRP can creatively address the ongoing struggles of a community and consider real-time responses.

HomeLAND

This past fall, I managed to obtain a ticket to the sold-out closing weekend production of a new musical Cuba Libre, a memory play that tells the coming-of-age story of a musician caught between two cultures. Comprised of the real-life stories of Tiempo Libre’s band members growing up in Cuba under Castro’s dictatorship, the play offers bilingual Afro-Caribbean music (known as "timba") to Portland theatregoers. After three years of development, the production was directed by Artists Repertory Theatre’s artistic director, Dámaso Rodriguez, a Cuban-American transplant from Los Angeles.

I think audiences loved Cuba Libre because the stories told on stage are not dissimilar to the headlines we read in the news. Throughout the play, I was reminded of the devastating front page photo of Syrian refugees washed up on the shores of Greece. Desperate situations beget desperate acts; people don’t get on rafts unless the water is safer than the land. Jorge Gomez, bandleader and founding member of Tiempo Libre, said during the making of the production: “It’s very easy to talk about things you don’t really know. You have to live it. Tourists go to Cuba and stay in hotels where they have everything they need. If you’re Cuban, you have nothing.” Set mostly in the nineties, the play almost felt dated, although those struggles and conditions represent modern Cuban life and resonate with political exiles and refugees.

The vibrancy and spirit of Cuba Libre depicted a version of the hardships of living and ultimately escaping Cuba. It also managed to make me homesick for a land that’s not even mine. It transported me to Los Angeles eight months ago: my struggle between ambition and romance, the beginning of heated political debates, and the music! I went salsa dancing every week in LA to destress, refocus my energy, and remember where passion lived inside me. In Cuba Libre, the salsa dance rueda circle in the final musical number had me in tears. I eventually found the salsa community in Portland and quickly remembered why dancing is my therapy. I don’t understand most of the Spanish I hear while dancing, but when the entire room starts singing along, energy rising, all clapping at the same time—I live for these moments. As I’m turned and dipped, water wells in my eyes because, to me, in that moment, that is home.

Cuba Libre offers the city of Portland an interesting perspective. It is an artistic rendition of what it looks like when a group of people are faced with economic hardships so harsh that they have no choice but to leave their home. The housing emergency in Portland is not nearly as desperate as Cuba during Castro’s dictatorship, but it now reframes the picture.

“Home” is caught between geographic coordinates you can find on a map and something you carry in your heart. Cubans carry on traditions to celebrate their culture with music, singing, and dancing. Native tribes hold ceremonies to pay homage to the land and their ancestors who previously walked on it. Both have found creative ways for their communities to honor—perhaps sometimes mourn—and celebrate their roots. Through these traditions, ceremonies, and transformative aspects of theatre, I’m able to find myself and my own sense of belonging, however temporary.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Thank you Jose Carrillo. Milagro Theatre in Portland, Oregon is in indeed currently presenting Contigo, Pan Y Cebolla, a play by Hector Quintero, considered a classic of Cuban drama. It is in Spanish with English supertitles and it is a beautiful production highlighting a variety of Spanish speaking actors that consider Portland their HOME; not cast from outside the city. The play deals with HOME in that it takes place in a Cuban apartment in Habana in the late 50's just before the Cuban revolution. The struggle to pay rent and buy food all while attempting to keep up appearances will be very familiar to many of us.

Thanks for sharing about Pan Y Cebolla, Daniel; it sounds like a beautiful production. I actually first learned about Milagro Theatre after seeing a PassinArt play. Shelley B Shelley, who I interviewed in episode two of my podcast, "Brunch with Strangers," spoke to Milagro's veritable blend of arts and culture. I was excited by and ran with this theme after close succession of these three events. Thankfully, HowlRound has granted me a series to discuss what I see on my travels further, so I don't have to compile every experience into one single essay. And, for the record, the fact that Cuba Libre did not use a majority of local actors was an issue I had discussed with several Portland Spanish speaking actors. The irony of including it in an essay that starts and ends with the concept of home was absolutely discussed in the original draft of this essay. When we cut it down from 2500 to 1400 words, the overall theme and feelings it evoked still held true, but I wanted you to know that it wasn't overlooked or lost on me. Thanks for sharing!

I hope this isn't your whole take on Portland theatre art as a force for healing; before you leave please visit MiracleTheatre whose work is exemplary in this regard, and it is ongoing.

Hi Jose, thank you for your comment. This was definitely not my whole take on Portland theatre as a force for healing, and would only even consider it to be described as such because the experiences I wrote about here presented me with this singular, common thread. That's why I wrote about it; sharing one aspect of many. I have discovered several wonderful art-based and aid-based organizations that use the Arts to address and process trauma in the Pacific Northwest... they just didn't all fit into this one essay. I'm excited to see how this series unfolds and how I'll be able to weave in the many amazing efforts about which I'm learning. Thank you for your recommendation of MiracleTheatre-- it's going on my list!

Not sure how or if this relates, but as a mixed blood member of the Cherokee Nation and much locally produced playwright/composer, I have spent 5 years writing a tragic musical about the removal experience from the viewpoint of a half Cherokee woman and her slaves.

I wanted to show both the positive and negative aspects of colonization in the music and dance.

I am stymied by the resistance of tribal members to revisit the emotions of the Trail of Tears and the reluctance to encounter slavery. I fear telling the emotional story may trivialize the spiritual story. How to get an audience by doing it entertainingly but with respect for the event is unknown. (I may bectoo close to this issue as my family's land is now being taken again)

The issues are so complex, I tried to simplify them in a tragic romance to reflect the emotions without addressing them head on, but maybe that only trivializes the real issues. If only my granny were alive.

Thanks for the opportunity to vent. I need to either abandon the project or find a way to move forward with honor.

Janiska

Hello Janiska: no worries about venting, I'm glad you shared! My instinct as a dramaturg is to connect you to resources that can help you finish your project. I worked for several years with Native Voices at the Autry, the country’s only Equity theatre company dedicated exclusively to developing and producing new works for the stage by Native American, Alaska Native, and First Nations playwrights. Randy Reinholz (Choctaw), the founder/producing artistic director and my mentor, has been at this for twenty-three years and often talked about that fine line you mentioned walking. It sounds like you've been at this for a while, so at this point, I would recommend teaming up to collaborate. Are you in Portland? Maybe Ms. Skelton could talk with you. I could also try to put you in touch with a local dramaturg to workshop the script. One or several dramaturgical conversations might help you move forward with your project. (Many dramaturgs maintain playwright driven workshops, allowing the writer to shape his/her own developmental path.) Sharing with a community and/or hosting a reading of the work with actors is also a great way to get feedback and work through how an audience might receive the issues in the play. Once you do finish, consider submitting to Native Voices-- they host a first look series and an annual short play festival Good luck!