The conversation came around to the prompt, Where do you see possibilities? In Bethlehem, a local housing attorney spoke of political will: changing zoning policies to allow tiny houses, and more multi-unit housing. A city councilor was encouraged by more diverse candidates so that residents could vote for people who seem to understand and think like them. Abby Goldfarb, executive director of the Lehigh Conference of Churches, exclaimed there’s been too much emphasis on new development. How to keep folks in their homes, maintain them, and keep them affordable? What if municipal and nonprofit agencies took on massive rental rehab, and created a municipal registry assuring that everything gets inspected, requiring landlords to provide copies of leases, and educating tenants on their right to counsel? Goldfarb emphasized the importance of hearing what’s worked elsewhere and adapting it here. We forget, she said, that there’s a world out there.

In addition to the connecting and organizing that these workshops provided, they also generated material that ashley and Mark used to create a play about housing. The production is a time-traveling, playful, immersive, and interactive experience that draws on popular culture to communicate housing-related facts, fears, and future fabulations. It is performed with variations each place they do the project, along with an ancillary event so, as Valdez describes, there are multiple entry points to community-wide reflections on local housing. Not everyone wants to see a play.

Though the same basic play is presented in each place, TMBHM is shaped based on the particulars of the places they work. Each iteration features local success stories with land banks, housing co-ops, community land trusts, or other models, combining facts with stories. In Bethlehem, a local Latina leader who was a single parent in a sub-par rental described taking a class about home ownership and subsequently buying a home. Each production also contrasts the average life expectancy in that particular city for people living in the most and least resourced neighborhoods respectively (a thirteen-year difference in Bethlehem). Auxiliary activities vary. In St. Paul, participants facilitated a teach-in; in Los Angeles, a walking tour. In Bethlehem, it was a daylong forum geared for people whose work is housing-related to envision the housing future they all want. Through stories, other sensory experiences, and hard facts, participants were personally immersed in the issues they deal with professionally every day.

The Forum

Grounded in Bethlehem, the latest TMBHM brought together deeply-committed housing advocates from the entire Lehigh Valley. Mary Wright noted that she knew of no effort to articulate a shared vision across organizations, which became their forum focus. Abby Goldfarb asserted that the opportunity to get away from the day-to-day details and dream was re-energizing, and her favorite part of the process. Although housing planning commissions are tasked with that role on an advisory level, they rely on experts, not broad public inclusion. Wright came together with sparks, Goldfarb, Smith, and City of Bethlehem Deputy Director of Community Development Sara Satullo, with additional support from Lehigh University professor Kate Jackson and Muhlenberg College journalism professor Sara Vigneri, to plan the convening that took place two weeks before the show.

Theatre added to the local housing conversation. Unlike conventional meetings, by immediately sharing personal stories, the workshops led to a deeper level of trust.

The group members concurred that theatre added to the local housing conversation. Unlike conventional meetings, by immediately sharing personal stories, the workshops led to a deeper level of trust. Participants experienced what they have in common. They focused on three goals within the context of imagining housing in 2050:

- Learning: What solutions are emerging to address the current regional shortages and affordability challenges?

- Connecting: What relationships are needed to address our housing challenges?

- Belonging: How might a culture of belonging for all Lehigh Valley residents make equitable housing for all possible?

Over seventy people from across sectors and local geographies gathered for the six-hour event envisioning a 2050 where no one in the Lehigh Valley is unhoused. Sitting eight people to a round table, and shifting tables as new topics were introduced, people got to hear many participants’ priorities around housing and the challenges they face. Satullo gave a Zoning and Planning 101 presentation so everyone understood basics about how government approaches housing issues. People shared their perspectives on values in Lehigh Valley that shape decisions. They tried to grasp the social landscape of 2050 to imagine how housing for all could be achieved in that environment, focusing on key economic elements that may impact housing; how views around issues including migration, diversity, and inclusion will inform culture shifts; the environmental or ecological factors that will impact housing; and what public, private, and philanthropic partnerships may impact the built environment.

The Production

Two weeks later, Touchstone produced three performances of the show. Upon arrival, we audience members were handed name tags; throughout the experience, we were called on and greeted by name. The spectator experience was very physical—we stood for most of the show so we were able to shift our attention to any of the four stages surrounding us, and were asked at the start to learn a line dance. This took us into our entire bodies, disoriented us a bit, and required we let go of how we looked and just do it. It changed the way we received the show.

The characters were all zebra-esque humans: they spoke and dressed like humans but had zebra ears and occasional quirks, like holding their hands up, elbows bent, in front of their chests, and moving as a little group, known as a dazzle. The main character was a glamorous cabaret singer with a fabulous wardrobe, all in black and white. The choice to juxtapose marvelous torch songs (e.g., “Surabaya Johnny” and “Mississippi Goddam”) felt like emotional release co-existing with challenges around the housing crisis we all share.

Why were the characters talking zebras? ashley and Mark said that they had to be animals to immediately catapult us into an imaginative space. Perhaps, too, because humans are animals at base and share those kind of needs. That made the characters both endearing and a little alien so even potentially preachy moments—for example, they expressed deep outrage about the relationship between the GI Bill and redlining—were not off-putting.

Bill George, Touchstone’s founder and a well-known local performer, spoke to the audience, in character, about losing his home at age seventy-two. The narrative is fiction with some details recognizable as George’s own. This fluidity between the imaginary and the real brought the subject matter—the sobering outlook for housing for the elderly—home.

Audience participation took a particularly creative turn when spectators were divided into small groups to play a game about the role of policy, values, pop culture, and beliefs in housing. Each group prioritized one concept per category. The focus was the conversation, not the outcome.

And Now?

The forum was a nourishing day, good for people to get away from their desks and connect with others. It was imaginative, challenging, fun, and informative. But what will come of this?

One of the biggest challenges with time-bound projects like TMBHM is follow-up. Unlike in other cities, the Bethlehem effort was not in collaboration with a housing organization able to organically integrate strategies learned into their ongoing work. ashley sparks lives in Los Angeles; Mark Valdez lives in the Twin Cities. Touchstone is not inherently a politically motivated company; the project would not have happened if Mary Wright hadn’t advocated for it and taken on the lion’s share of work. But she is already on to the next Touchstone project and cannot dedicate herself to follow-up.

One concrete action was sharing the list of invitees so people can be kept apprised of other housing equity forums in Lehigh Valley. Another is that students in Kate Jackson’s Community Based Participatory Research class at Lehigh University are interviewing attendees about their experience and analyzing data the forum collected about community values, policy visions, and the obstacles to a future with a housing guarantee.

Local organizers Smith, Goldfarb, and Satullo concurred in an end-of-project interview that impact would take shape over time. They praised the interactive and story-driven facilitation method, allowing space for community members to engage with each other and housing leaders, in contrast to speaking at a public at community meetings. TMBHM was a rare opportunity to put limitations aside and dream big. All will look for opportunities to develop such tools moving forward.

In regards to the three goals of the convening and the overall goal of imagining together housing in Lehigh Valley in 2050—all three deepened alliances with other housing advocates because they got to know them better than at most convenings. They found themselves engaging around housing with a more diverse group than usual. All three felt more connected to Lehigh Valley as a whole.

That is what theatre brings—an experience of each other that reveals more than our public selves, touching the deeper waters of each other in such a connected way that we will never be all right until we all have decent shelters in this wide world.

Participants in all five TMBHM venues emphasized the project’s success as:

- A space in which to get back in touch with their ideals: Some housing advocates remarked that the biggest missing ingredient in this effort is imagination—thinking gets smaller because it is focused on policies that can get passed while the problem gets bigger. Theatre is low enough stakes that people can actually talk about hard-to-reach ideals.

- An effective, interactive method of public education about the issues and options surrounding equitable housing: In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, educator Paolo Freire distinguishes between the banking method of education, whereby information is deposited into people’s heads, and the dialogic method, e.g., learning by way of conversation. TMBHM embraces the latter.

- A conduit to deepen relationships with others, not based on professional roles, to improve local housing options, grounded in everyone’s need to live somewhere.

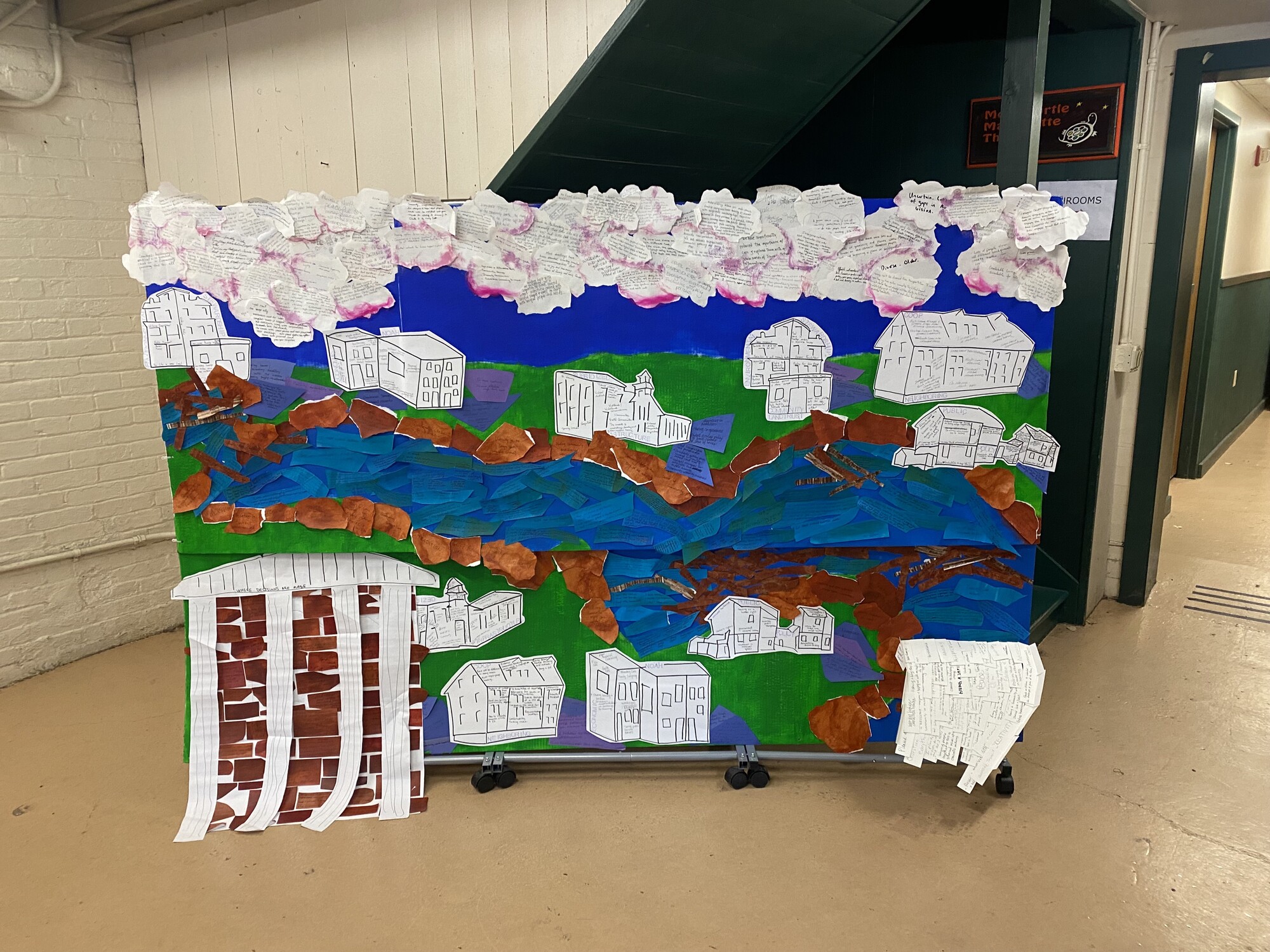

In Bethlehem, the central image that ashley chose for the TMBHM forum was the Lehigh River. A river is to a community as veins and arteries are to a human body, bringing life blood to and from the heart to the furthest extremities, connecting and nourishing all the parts. The road to equitable change that this project offers is also connected to a heart, that of the community, so people there can connect and fall in love with each other. We want to take care of those we love so we have to fall in love with those we live amongst. I understand love here as a sense of being so connected that you feel someone else’s suffering as your own.

Family, at its best, is an ever-expanding circle—from mother and child to family unit to relatives by blood or behavior, to people connected by something foundational like tradition, spirit, or place. In a town the size of Bethlehem, the idea of community of place is very concrete, even though, as Benedict Anderson observed in Imagined Communities, most people in a given community will never know each other. I’d argue that the best chance for policy change includes people in a given place experiencing each other in a way that makes falling in love possible. And that is what theatre brings—an experience of each other that reveals more than our public selves, touching the deeper waters of each other in such a connected way that we will never be all right until we all have decent shelters in this wide world.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Terrific article Jan. It so clearly walks one through the assets theatre can bring to important civic conversations. As always your writing is as much storytelling as reporting and presenting the details. It lets your readers imagine this process as possible in their own communities. I could imagine this in Red Hook- or in my less known- but home community of Flatbush. Inspiring to think about the possibilities.

Thanks, Martha. If there are people in your community who'd like to talkabout this process in more depth, I'd be happy to come by!

Thanks, Jan. As always, you combine good storytelling with insight and inquiry. This project (and the work of our beautiful friends Mark and Ashley) is situated squarely in a sort of practice, process, event and tradition) that builds our civic imagination. We need more of it. Grateful to Howlround giving it some space and light here.

I'm so grateful for your affirmation, Michael. Thank you!!

I' welcome comments about this article... Thanks, Jan