Acting in Solidarity

Working for a Living Wage

On Thursday, September 10th, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a push to increase the state minimum wage to $15 an hour. On the heels of Fight for 15’s victory in New York, a movement led by fast food workers demanding $15 an hour, we can all celebrate a major victory for working people in New York. In the theatre, many of us work part- or full-time low wage service jobs to support ourselves while we create work at night, and many of us can expect a raise if this bill becomes law. A living wage will certainly make a life in the arts more attainable for many.

In many ways, the current stratification of many poorly paid and underemployed actors with a few full time folks at the top mirrors trends in the other sectors of the economy.

However, a $15 wage also highlights the state of pay within the arts: it is far above what many professional theatre artists and actors, especially those early in their career, earn. A recent contract paid me $300 for an entire show, which—only counting time spent in the rehearsal room and in performance—works out to about $3 an hour. I was paid a stipend as an independent contractor (meaning this sum was even lower come tax time) for what amounts to over a month of full time work. Independent contracting provides a convenient loophole for theatres who want to pay actors but can’t afford wages, but such arrangements are far from sustainable.

I don’t fault small theatres for this—it’s a tricky situation. Artists want to make work. Theatres with small budgets want to pay people. We’re all struggling to make the best of a bad situation when it comes to funding. In New York City, Actors’ Equity Association’s (AEA) showcase code allows union actors to work for no pay to “showcase” themselves for future employment. Depending on your point of view, this might be a way for interesting work to get made by folks who are between jobs, or a way to exploit highly skilled artistic laborers. The reality is somewhere in between, as reflected in contentious changes to L.A.’s 99 Seat code. Things are often much worse for actors working without union protection, especially in cities where future employment under an Equity contract doesn’t exist.

We can think of this in terms of the market: if you can’t afford to pay actors a meaningful wage, you can’t do the project—but where does that leave work without broad commercial appeal, or young artists without the infrastructure to secure funding? Many young theatre artists are engaged in a level of entrepreneurial risk while developing work, often over extended periods of time—investing their labor for potential return when the work is shown. These shows occasionally break even on costs, but if you include the unpaid labor in your math, that picture changes drastically. Still, regardless of wages, they have an ownership stake in the work and thus have a different relationship to production than many directors, actors, and designers working for hire. Some artists are finding their own way to navigate the economy, and maybe make a living, but our institutions are failing. Even with Kickstarter and Indiegogo, the current economic landscape appears unable to support a life in the theatre for most of us who have chosen it and invested heavily in our training.

In many ways, the current stratification of many poorly paid and underemployed actors with a few full time folks at the top mirrors trends in the other sectors of the economy. In higher education, a field where many artists seek refuge from the poor pay of the art world, most courses—over 70 percent—are now taught by adjuncts and other contingent faculty often making less than minimum wage. Meanwhile the middle-class ranks of tenure track faculty stagnate—even as administrator salaries go through the roof. So it is in theatre: some actors make a decent living, many as members of AEA or in other media, while most support themselves with other employment. The apparently vast labor pool of actors even occasionally produces some anti-labor rhetoric from AEA.

(Library of Congress).

AEA’s current campaign encourages consumers buying tickets to national tours to “Ask if it’s Equity.” What this often implies is that the tours are of lower quality because the actors are not union. While it ostensibly targets producers and presenters, it nevertheless shames working actors by relying on consumer perception to pressure presenters. This is AEA’s latest response to the on-going issue of national tours, from the loss of union jobs to the introduction of lower paying contracts to win those jobs back (audiences might be better advised to ask what tier the Production Contract is). AEA, just like every other theatrical institution, is attempting to make the best of a bad situation—while failing to realize their fundamental strength as a union.

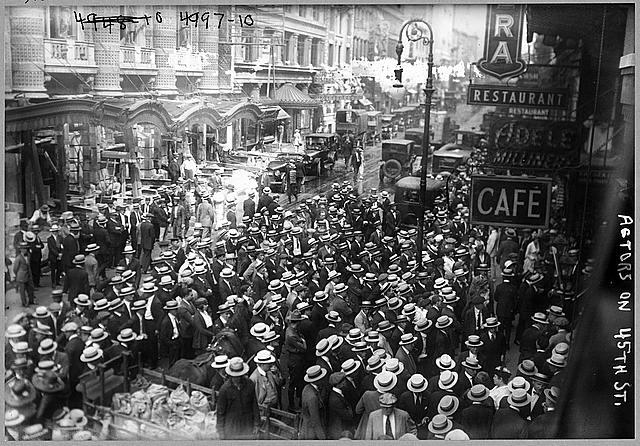

AEA could organize actors. Whether led by Equity or not, such a drive may be the only way to push the economy forward. Actors across the country are mostly unprotected, un-unionized, low wage workers—a situation not far removed from the one that occurred one hundred years ago when Equity was formed, when actors joined in solidarity with the working class of New York City and made acting on Broadway a safe and stable profession. Union membership alone will not change these conditions (indeed, many actors work for little or no pay under AEA’s own membership candidate program): our demands must be some kind of broader restructuring of the economy, such as a renewed National Endowment for the Arts—the body that Equity once helped create.

The economies and structure of the entertainment industry have changed in enormous ways in the last century. We now have a theatre industry structured primarily by non-profits and precarity. While we will all be less precarious if we’re working at $15 an hour in our day jobs, we will still be artists only part-time. A living wage means more people will be able to afford the arts in their life, to both attend and participate in theatre: a massive democratizing impact on our field. But this victory is only the beginning of the fight for a truly sustainable theatre: we need more public funding, more investment in infrastructure, and more long-term security for workers. Unlike other sectors of the arts world, the performing arts benefit from being organized into strong unions that could fight for change. At the end of the day, there’s one thing we need to create thriving, vibrant, high-quality theatre: jobs.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

"Independent contracting provides a convenient loophole for theatres who want to pay actors but can’t afford wages, but such arrangements are far from sustainable.

I don’t fault small theatres for this—it’s a tricky situation."

While it is a tricky situation, it's also illegal and very risky. It is clearly employee misclassification if any employer treats a worker as an employee but pays and classifies them as an independent contractor. It is not what you agree to on paper, but rather the business relationship that determines the employment relationship. If you control the how, when, where, and what work a worker does, it is most likely an employer/employee relationship. If actors were truly contractors, it would be a client/customer relationship - meaning the theatre is the actor's customer/client.

Employers found to be misclassifying workers can be liable for back taxes, back wages, and potential liability in a civil suit. It's not only unsustainable, but unethical and illegal to defraud workers of their workplace protections. Theatre and the entertainment business DO NOT have an exemption from the Fair Labor & Standards Act, and we must stop pretending that employment laws do not apply to us.

Yes, though many types of production arrangements aren't so simple. Often, there's no money being made at all. The theatrical endeavor can cross out of the space of business and commerce and into the realm of the aesthetic. The upstart group with no funding that pulls together kitchen scraps, friends working together and taking home what they can, etc. And showcase arrangements as codified by AEA! I'm not advocating for new enforcement of these regulations--we wouldn't accomplish anything but hitting the little guy, though there are surely some worthwhile targets. I'm also not advocating that producers don't have a responsibility to treat workers fairly. I'm advocating for improving conditions industry wide, and I don't think that shutting down so many theaters would do that and create a thriving American theater. Funding, though, might - can we find a way to enable such small non-profits to pay wages?

The fact is that these conditions have spread wide beyond the theater. Independent contracting has spread to unlikely operations like retail. Internships go unpaid, not just in theater, but in publishing, banking, and so on. There are Equity houses that will issue enough contracts to meet their minimum and hire additional actors for nothing to fill out a show. There are theatres that people pay to work at as apprentices.

We need a larger framework to think about these things if we're going to bring about meaningful change.

You know it's the end of the road when a union says it's ok to work for free. What's needed is a nation that gives 100% support to the arts, out of national pride. A USA national theater, with support for all regional theatres. At least a National Endowment for the Theatre, live, stage, touring companies for starters.

Thank you for writing so eloquently and efficiently on all of these issues! As an aspiring arts administrator, these are issues I've spent a great deal of time thinking about. I have noticed that in the "fight for 15," the pay scale for independent contractors has barely been touched, and it's something worth mentioning and discussing further. However, the issues of choosing to go AEA or stay non-union, and what the union can provide, as well as the hot topic of "Ask If It's Equity" are in heavy rotation among conversations I have with my friends, many of them young actors. (Luckily, I am not tasked with the choice of going equity or not, as I am neither an actor nor a stage manager.) Obviously, it's great to have the protection of a union behind you, but for many of them, choosing to go equity means they will face a certain decline in the jobs available to them. What can be done? A friend who is a member of IATSE suggested perhaps AEA could develop a "local" model, like IATSE. It's not as if regional not-for-profits want to go non-equity, but it's all a matter of cost. Perhaps if a regional local model were put into place, there wouldn't be the stratification among working/non-working actors that you mention. Also, perhaps more NFPs would be able to hire more union actors. Just a thought! Thanks again for bringing attention to these issues.

Thanks. There's a lot more to be said, and a lot more research that we need to do - I'm hoping Equity will pick some of that up. AEA does have a certain model of what could be called pseudo-locals, as they call them Liaison Groups. These groups have no voting power, though, as we saw in the change to the LA Plan despite the local vote being against it. We have one here in Buffalo, and I was around in Albany when the Liasion there was being formed. Here in Buffalo, though, we have no Equity houses. Nearby Rochester has one, though we do have a local contract, the Buffalo-Rochester Special Appearance Contract - which AEA claims has resulted not in more jobs, but just lower wages. A handful of union actors get hired, almost all of whom are white men, and some non-union actors get decent paying gigs, but it puts a kind of soft cap on the potential of what can happen here.

For me, it's not a question of going Equity or not, I think that misses the point, and it's not even an option outside of a handful of major markets. It's less about union protection than being able to make a living. Ultimately we need more jobs, period - part of my point, maybe a topic for another time, is that there's a silent majority of working actors in this country who aren't in the union, or who are but are working under agreements like the Showcase Code, that AEA should nevertheless be advocating for in order to not only increase membership, but to create more jobs and improve conditions across the industry. Put another way, it's that the conflict between wages and jobs that came up with the new LA agreement isn't really a conflict between those two things (which is similar to conservative rhetoric about minimum wage increases in general), but actually a bigger problem of resource allocation to the arts that we need to confront head on. There is work being done and people deserve to be paid for it, especially when that cultural work pays dividends to local businesses and municipalities in tax revenue.