On Tuesday, 11 March, ArtsEmerson and Toshi Reagon decided to postpone the Boston, Massachusetts presentation of Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower to October 2020. A week later they gathered on Zoom to reflect on that decision, the state of the Now, and prognosis for the Next. The following interview is an edited transcript of the conversation, which you can watch in full below.

Answering the Call to Pause

On Deciding to Postpone Due to COVID-19

David Dower: David Howse and I wanted to talk to you today, Toshi, about the decision we made to postpone your production of Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower at ArtsEmerson and to, ultimately, cancel the remainder of our season.

We came to that decision through the conversation you and I had, and also a conversation we had with our staff. Those two things shifted our sense of priorities in a profound way. I wanted to go back through it a little bit with you, and I hope our conversation can help people who had to make a similar decision know that it came from a place of power and a place of progress.

I remember being on the phone with you, Toshi, with my normal, “I’m going to take care of this artist. I’m going to assure this artist we are going forward.” This was Tuesday, 10 March, the minute before everything fell apart. I was still in a place of: “Toshi, this is all going to be fine.” As I remember it, you said, “Yes, I appreciate it. I’m excited to do it, but also: What if we didn’t do it? And what if we instead listened to the work?”

Does that resonate with you as your experience of the call?

Toshi Reagon: Yeah. I really was thinking about the work itself, Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and also Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Talents and her book that didn’t get come out, Parable of the Trickster. I was thinking about togetherness and what it means to be together. COVID-19 is an event happening on the entire planet. We’ve been living under events for the entire planet forever, but I think we’ve fallen for the idea of borders, which have been gated over time, and the different countries and the systems that administrate them. But we’ve had a climate crisis on Earth for a long time now, and that climate crisis doesn’t see borders.

It’s clearly time for all humans to have a different understanding of togetherness. When I felt your energy, which I thought was spectacular and wonderful, I also was like, “But what about if we could postpone the production because it would put us in a practice of our togetherness in a way that humans usually don’t use?”

David Howse: Prior to the call you and David had, we had shared with our staff our intention to go forward. I kept saying, “We’re trying to create some sense of normalcy in a very abnormal time.” That hit as flat as a brick. People were like, “Oh, no, no, no. You could not actually say normalcy in these times.” We practice a lot of what we call shared leadership here, so our staff was giving us very candid feedback around some of the decisions we were presenting to them. I was listening deeply and feeling their own anxiety and their notion of our betrayal of own values by just plowing through.

While you were on your call with David, I was processing what I just heard, what it would mean to ignore what we were hearing from our team around the values we’re actually fronting and presenting as the leaders of this organization. It was quite fortuitous that these things were happening in separate offices, side-by-side. When David came into the office, we were in sync with each other. Those two things came together, and we were like, “We’re crazy if we think it’s going to be business as usual.”

Our staff experienced the evolution from us saying a thing, listening to feedback, and responding differently. We believe our artists are the keepers of truth, that they will lead us. It felt completely right to say that we were completely wrong.

Toshi: Wow. That’s what the world needs, more processes like that. We don’t all know everything. Most of us are led by our hearts and our desires, and that’s different for everybody. When there is such a powerful common call, it’s a unique situation, and I think people on Earth are afraid of those situations. I don’t blame them because people have not been treated well with common calls. Common calls are usually really violent, really destructive, taking something away from people. It can happen on a dime. There have been multiple well-documented vicious moves on Earth, by humans, that would make you not trust a moment like this to be something positive. There’s a lot of reason to be like, “We’re going to carry on.”

I really feel that, and it’s not even about “normal.” Sometimes it’s just a small way we handle anxiety, like: “If I’m working, it’s not happening.” The Earth has been begging us to stop and consider our places on it and to consider all of the breathing and living elements on it. This is an opportunity for us humans to deal with our destructive tendencies and our overuse of resources on the planet and the ways we don’t love ourselves. Sometimes things feel so big and out of touch, and if you had to solve every single thing, you would have to agree on what to solve first and then you’d have to agree on how to solve it. Sometimes we can just say, “What is being offered?” And right now what’s being offered is a gigantic pause to save people from getting sick and dying.

David Dower: You said in an email, Toshi, that you hear a lot of talk about the apocalypse. You don’t mind contemplating the end, but you’re not here for the apocalypse—this is our moment, and this is our time. We’re going to walk together into a future, not an apocalypse.

This is an opportunity for us humans to deal with our destructive tendencies and our overuse of resources on the planet and the ways we don’t love ourselves.

Toshi: I love some of the things people are writing, and I love the openness of talking about the apocalypse, but I’m not here for it. I’m not loving all the conversations enough to be like, “Well then let’s all just do whatever we want to do and be how we want to be.” The idea of apocalypse, like the end of the Earth, the end of time, the end of everything… I think there have been so many ends and so many horrific ends on the planet by humans, I’m like, “No, you don’t get to have the excuse of the apocalypse to behave in whatever way you want to.”

The Earth will contain itself, but will it contain us as humans? We need to show some reason for the Earth to contain us. We need to make and broadcast on another level to be in alignment with the Earth. Sometimes people think, “It’s happening,” and I’m like, “But you’re still getting delivery.” We’re still having a simple conversation around plastic bags.

There are people on the planet—and there always have been people on the planet—who live in conditions that are so horrible. None of us can tolerate them, and those people can’t tolerate them. And we allow it to happen. What I’m suggesting is that this is an actual opportunity, because the wealth on the planet is there. It’s not like we don’t have wealth. We designed this system. We designed an economic system like this, so it’s not like we don’t have enough to be brilliant about our care and how we are on Earth. It’s that we are not all in agreement of how we should live and exist on the planet. That is a constant and consistent war humans have played on the Earth since we got here.

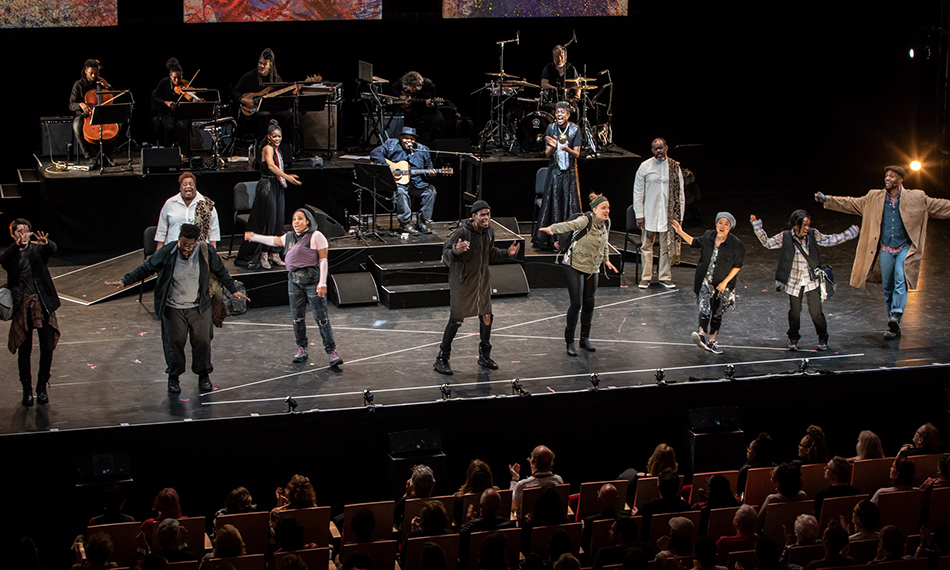

Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower at ArtsEmerson

We’re the generation with so much information—we actually have an understanding of resources. We have experts in science. We’ve been to space. We have seen the universe. We have several different practices around wellness. We have all of these things. We have this song in Parable called “What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?” The world is on fire, and let’s do what we actually have to do. We also have our gigantic emotional selves, and we have our... I don’t know about you, but I like what I like, and I want what I want, and I like what I like, and I want what I want all the time.

I’m not always in alignment with my family, let alone the planet, so this is an amazing time to not only execute this indoor life—which I hope is the right thing to do and which I hope will help us in our healing from this worldwide virus—but also do other things. We should not go back to exactly the way things were before. We should not accept the same low-level outcome of mainstream news. We should not accept the same boundaries of executing our election. We should get out there and vote and vote and vote and vote, but vote with our foot on the throats of the American government system.

This is the time to calibrate your life in a way that makes sense not just for your existence but for the existence of your children and of your children’s children and of that tree across the street.

What I think Octavia Butler was saying to everyone is that we can make decisions intentionally, not when everything is terrible and awful and we feel overwhelmed, but as a practice in our lives all the time. We’re not going to kill each other. We’re not going to steal from each other. We’re going to watch out for each other. These things are significant, but if we don’t carry them with us, then we will all be systemic in acts of wars for the rest of time. That’s the big, beautiful moment of togetherness that we’re in. I hope it won’t happen too much, but we should take full advantage of it happening now.

David Howse: Earlier you mentioned the call to pause. I would love to hear more about what that pause is, because my sense is that there’s something we’re supposed to be learning here. I agree we shouldn’t come out on the other side the same way we went into it. But what does this pause require of us? I just said to our staff our tendency is to try to be even more productive as we’re working from home, which just creates a different kind of burnout. There’s this balance of trying to be able to move forward and plan for the return, but also taking enough time to pause.

How do you think about both pausing and acting in this on-fire moment?

We should not go back to exactly the way things were before.

Toshi: I think what this is causing us to do is realize some of the perfection in the systems we have already, which we’ve taken for granted. Education is so important, all kinds of education. Education you get from your friends and your grandparents, and education that comes through music, education that come through art. But teachers are a neglected workforce on the planet, and they have so much responsibility. They’re supposed to know all of this information that they can pass onto students. They’re not just supposed to be there to watch your kids. Everybody’s upset: “Well, who’s going to watch my kids?” Something about those words—school, classroom, teacher make you go away, and you just go do your job. You expect it’s going to be handled, but it’s a disintegrating system.

The level of violence that’s happening in schools is just… If you know nothing else, every person in America must know that the government does not care if kids get shot in school. It is just true. There’s no way you can look at it any other way. Government doesn’t care if you, eating dinner in a restaurant, get shot. Government doesn’t care if you, in the grocery store, get shot. Government doesn’t care what you’re doing and you get shot. Does not care. Every. Single. Person. Every single person who has been elected to office has a level of “don’t care” attitude because they have not done everything they possibly could do to stop it. They just haven’t.

If you know that, then you already know what they think of teachers. And, if you already know that, then you are part of the thing that allows this structure of education so that we can run whatever economic systems we are running. If you look at Black people in this country, Black people were... You are brought here. You are in such a level of torture. You don’t have language for it, and yet you actually went and created language for it. We created a way to communicate what we needed, to house ourselves in conditions that no one should ever experience. Right?

Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower at The Public Theater

My mom had a teacher, Mrs. Daniels. She had one classroom. She negotiated education during a horrible time in our country for Black people. She taught all the grades in one room. She got milk for the kids every day. Mrs. Daniels is a warrior. I want to do a musical on this Mrs. Daniels. And I think teachers are like that. They’re warriors. They figure out the way out of no way. Out of something that’s just insane.

David [Howse], earlier you said: “What I have learned by having to homeschool my kids is that teachers are amazing. They do so much with so little, and I need to unite with them.” That’s going to be different for you, and I think, hopefully, different for everybody. What can come out of this is a level of production that is more balanced because right now, our work— whether it is righteous or not—is what’s validated. So any excuse to overwork ourselves will do. But then you realize the system is broken because every day you’ve been sending your kids off to school, and you’ve been neglecting that system. You haven’t involved yourself. When the teachers are like, “We’re going to go on strike, we’re in agony,” you’re a little angry at them because now who’s going to keep your kids? There are all kinds of systems like that operating, and people are getting a chance to meet them.

With my residency in Boston we’re going to do a workshop on facilitation. Facilitators are people who help other organizations or groups learn how to have a practice around doing their work efficiently. There are different kinds of facilitators for anything you can imagine, and I have several friends who do the work. They are wonderful and awesome, and they are also mostly exhausted, working all the time.

The workshop is going to be a check-in on facilitators. How are you creating a practice for other people when your practice is actually overwhelming you and your life? Is this proper sacrifice? Harriet Tubman did excellent sacrifice. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee did excellent sacrifice. Are we actually doing excellent sacrifice? Or are we just wearing ourselves out and creating inside of the same systems that says, “Work, work, work, work, work. Make money, make money, make money”? And even if you’re also doing beautiful shows and even if you’re also helping somebody organize their office better, are you actually doing the same thing that is an exhaustive system that will eventually make you sick and not happy?

It’s a challenge to ourselves to think about what the excellent sacrifice we are committed to is as warriors in arts and culture, or warriors as organizers, or whatever our calling might be.

David Howse: I really love that notion of excellent sacrifice and what it means; there’s the corollary in the business world, “Working smart versus working hard.” So many of us think we’re doing the thing we do to sacrifice for the people, when it probably is perpetuating that other dynamic, being in the system just doing more work. But to what end? It’s a challenge to ourselves to think about what the excellent sacrifice we are committed to is as warriors in arts and culture, or warriors as organizers, or whatever our calling might be.

Toshi: Heck yeah.

David Dower: I had to turn myself inside out, Toshi, after our phone call. Theatre people are trained that the show must go on. That’s our thing. That’s what defines us. Like postmen always deliver the mail. Our shows always happen. Responding as a community for me, in all my years of community organizing, has been about coming together, wrapping ourselves as tightly together as we can and standing particularly with the afflicted or the at-risk as closely as we can and holding ourselves together like that. Those are not excellent sacrifices particularly. They’re called into question in this moment.

A couple of years ago in Boston, we had a horrible snowfall, like ten feet of snow in eleven weekends, and our instinct at ArtsEmerson was always, “Let’s do the show.” Even during that time, many of our staff members would say, “But this is what it’s going to take me to get in to be your usher. This is what it’s going to take for me to be backstage when that happens.” But it was like, “Yes, you’re in the theatre. Do it. Do it. Do it.”

And then this crisis finally smacked a brick in the head, like, “No, actually, don’t do it. Don’t do it. Don’t do it.” That’s the actual expression of love. That’s the expression of togetherness, don’t do it. Toshi, you gave me the phrase “standing together by standing apart,” and it’s what we put up on the marquee. I had been asking people to do this other kind of sacrifice because of it was instinctive. It’s been really remarkable to be turned inside out. My instincts were actually counter to my values at the end.

Toshi: This idea of “the show must go on” is an idea of being stuck. Several long-term theatrical institutions, like Broadway and others around the country and around the world, have been around for one hundred years or more, and we have structures of how they exist. I’d say we’re at a time when most of them need to change. What do we want to keep about our ways of communicating and creating that have become mainstream, and why? We’re at a time where all that could go away.

David Howse: Absolutely.

Octavia E. Butler's Parable of the Sower at ArtsEmerson

Toshi: Octavia’s idea of change, the idea of meeting where you actually are, the idea of serving your community… Theatres are so uniquely designed to be a real-time holder of their communities and their communities’ creations. Whenever I’m in a place where I have to pitch Parable, I’m like, “Whether you do it or not, consider yourselves the twenty-first-century mass meeting holder. Consider your building and what it can offer your community.” I would be like, “You’ve got wifi. You’ve got air conditioning. You’ve got all these rooms. What could you do?” All of these theatres that are closing actually have an opportunity to restructure the little fuzzy things that have been on their minds and the systems they’ve created.

People asked me about Parable and Broadway all the time, and I am like, “If it goes to Broadway, I’m not going to be in it because I’m not singing eight shows a week.” But I am also like, “Why is it like that?” Maybe that worked back in the day, but does that really work now? So many good shows come up and close because they just can’t sell that many tickets. I wonder why there isn’t more innovation in terms of putting more than one show on in a theatre at a time. We did a show at the Paris Opera House, which is old as crap. You send your set to them, they take it apart and learn how to break it down and set it up in two hours. Why don’t we have more innovation like that here? Why does there have to be one show in a theatre per week? Why can’t there be two shows? Why can’t it be a one-person show and a big show? Why can’t it be all these things?

Like anything, change is really difficult if you’re very, very happy with where your structure is or if you’re very, very used to what your structure is. But I think what we tend to do is hold onto whatever we think that structure is, and as it lessens and lessens and gets harder and harder, or gets more and more violent, or more and more restrictive, we’re like, “Let’s just keep it as much as we can.” That is not going to work. We have an abundance of opportunity right now, and it will shift everything. We will not land in the same place we were, and we will not be comfortable with all of the things that come out of it. But to actually be a participant in change, to be an eyes-open, heart-expanded participant in change, even uncomfortable change, is what we all need. It’s definitely what theatre needs. And it is what this time is calling for.

David Dower: I have one other question. David and I were trying to listen to language, both in the media and in the public sphere, and then listen to you as well. I’ve been hearing it said a lot now that we are in a war with this virus, and this is a war. I’m not sure that’s helpful. Maybe it’s easy to rally around something that’s a war, but I wonder if it is also just failing to listen?

We need to do better with what we have.

Toshi: Most of the people I see talking about the virus in this way are rich men in power who’ve been in power for a while. They are presidents and governors and corporate leaders. That’s a very typical language—a confrontational language—that’s used when trying to rally the people en masse. If we all think we’re in a war against something, that’s the outside war coming to get us. But no: I believe the virus and all of the viruses come from us. They evolve out of us and who we are on the planet.

It could be a collaboration of events that led to its creation, but they’re ours. They belong to us. They belong to humans. All of the illnesses and the sickness and the climate issues, these belongs to us. If we’re at war with it, we’re at war with how we are on the planet. We’re at war with our systems. We’re at war with our institutionalization of things that should be easily accessible. We’re at war with how we treat the food on the planet. We’re at war with how we allow corporations to own resources for the Earth.

Before you can conquer a virus, you have to conquer your fucked-up practices that created the virus in the first place, and you’ve got to be honest about that. All of us have to be honest about that. And it will happen again. It’s not like this is one-and-done.

Every person on the planet has a right to access water, food, shelter, company that’s not trying to abuse it and kill it. Everything around the ownership of bodies and being in charge of bodies and creating systems for bodies, whether medical, industry, drugs, workforce… Somebody is making a lot of money out of it, and it has to stop. It doesn’t work for everybody. It just works for those few hundreds of people who profit off of the systems, and even if I enjoy the products and even if I enjoy takeout, and even if I enjoy driving a car, even if I enjoy flying on an airplane and going someplace beautiful, if you tell me the consistent abuse of those systems is that we will all get sick and die, I want to try to learn other systems to do things I enjoy, ones that don’t kill us eventually. That is a big thing for all of us to look at.

When you’re born, you’re so close the Spirit, and then you get information, right? Sometimes we forget how much we should cover young people so they can have access to their known information when they get here because that known information is for all of us. We think we have so much to teach young people, and we just shove things down their throats so fast. It’s as if they come here and they’re like, “I know why I’m here,” and we’re like, “But learn your ABCs.”

We definitely have to understand that this belongs to us, and we’re at war with the things in the systems we have that developed and with the way we’re negligent, because what this is showing is mass negligence at the highest level of leadership around the world. Just the idea of information and the idea of ownership of information and then the ego… If our country is falling apart, what does it say about this country we don’t like? We need to do better with what we have. We need to do better with what we understand, and we need to be available for the systemic changes that have to come about to put us more in harmony with the Earth. But if we’re at war, we’re at war with ourselves.

David Dower: Bingo. That’s a great place to land.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here