The Beauty of Complexity

Or the Death of the Pure Aesthetic

Delivered at ArtsCrush in Seattle, Washington on September 10, 2013.

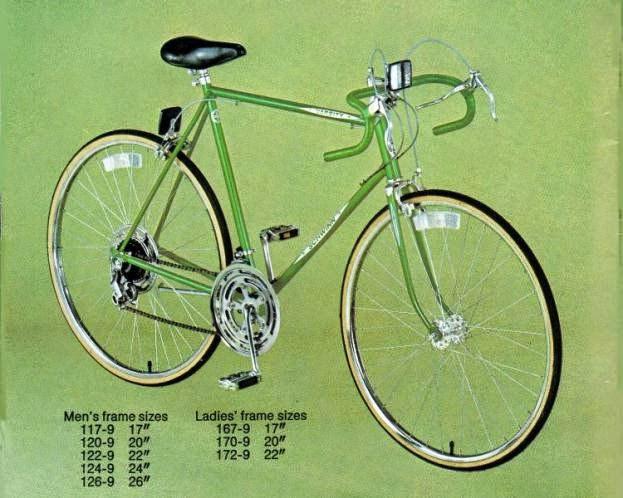

In 1977 at the age of eleven, I wanted only one thing, a lime green Schwinn ten-speed bike. At that time my room was lime green, my bedspread a gingham-checked lime green with matching curtains. I loved lime green and I loved riding my bike (a three-speed red Schwinn with white banana seat is what I would be leaving behind if I could figure out how to get my hands on the lime green Schwinn).

I grew up in a family of very modest means and I knew that this request was a big one. I think the bike cost about $75 and I can’t think of anything I owned at that time that was so expensive. I thought my chances of getting it were slim. But I got the bike for my birthday and I rode it well into my college days. This began my love affair with biking, my second love next to theatre.

My love of biking is hard to talk about. It’s a nuanced obsession of great complexity usually reduced to a brief conversation between my spouse and me:

How was your ride?, she’ll ask.

I reply with good, great, or it sucked.

Good means many things: the wind was at my back on the way home, so I’ve forgotten that it was in my face on the way out. It might mean I was up over 14 miles per hour the entire way. It sucked is all about wind, cold, mechanical things, and bad drivers. And great usually means at least five people yelled from their cars how awesome my tats look and that I felt my heart pumping; that motion and I were one and the same.

Today I want to talk about how the ways in which the arts, and particularly theatre, make the heart pump. I want to talk about the way in which what constitutes great and transcendent art has changed so drastically in only a few years that we are engaged in a moment of revelation and revolution about the changing nature of beauty and who gets to determine what that looks like.

How one walks through the world, the endless small adjustments of balance, is affected by the shifting weights of beautiful things.—Elaine Scarry from On Beauty.

And for me, the beauty of riding is in the complexity of those small adjustments, it’s a sport of balance and many days the balance is imperfect, but on the right day, there’s a possibility for transcendence. I love biking and art because of that rare day when balance is achieved and something beautiful emerges.

Here is the preeminent rock critic of the 1970s Lester Bangs who wrote for Rolling Stone and Creem redefining beauty as he begins to fall in love with what will soon be called punk rock:

This is the beauty of rushing many-streamed complexity which when it finally grabs you can literally take your head away so that you’ll find yourself. . . it demands involvement on the part of the listener. You’ve got to pay attention to it, it’s not for the passive listener but shit, here I go sermonizing again.

Lester Bangs represents a moment in history and a movement…everyone wanted on the bandwagon of the youth movement…and all the young people wanted involvement. They wanted to make rock n’ roll, forget that passive listener crap!

Lester Bangs’ out there style, his ability to bring the idea of the “other,” the punk rocker in particular, into the mainstream and his ability to redefine beauty in the music industry was about redefining beauty as something active, not passive.

And beauty in the theatre has banked on a certain willingness for watchers to be relatively passive, anxious to see what has been curated for them for most of the first fifty years of the not-for-profit theatre movement. But those pure watchers of the aesthetics of others are becoming more difficult to find. People will watch now but with a much greater investment in their own abilities to make the things that interest them. The world has changed. What was once considered active—watching a play in a dark theatre—is no longer enough. Too many watchers are now makers and have higher standards for how they spend their more passive time in cultural institutions.

The world has changed. What was once considered active—watching a play in a dark theatre—is no longer enough. Too many watchers are now makers

Theatre is unlike cycling in both its propensity toward passivity and in its lack of accessibility. Biking is active and a large data set is likely to ride a bike sometime. But let’s be honest, theatre and art making are things that privileged people tend to think about and are more likely to make and watch.

Pierre Bourdieu was a cultural theorist who thought a lot about the privilege of taste, and the accessibility of beauty. He argues that art is made at a distance from experience. That those with access to making theatre and paying for expensive tickets to watch it can often do so at a distance from the immediate needs of day-to-day living. It’s from this privileged vantage point that artists, audiences, and critics come to believe that art can become transcendent, that it can in Bourdieu’s words achieve the “pure aesthetic.”

Let me give you the simplest example of what Bourdieu means by suggesting we make art at a distance from experience. I worked on the play In Darfur by Winter Miller as a dramaturg. People were dying in Darfur as we were making the play, but I was watching the play thinking about; is too much exposition here, and was that scene in the right place? I could watch a devastating rape scene with aesthetic distance and think about sight lines, for example. In its horror of subject matter and real time urgency, I was invested in making sure the play achieved the pure aesthetic of my definition of good theatre.

As makers and watchers we come to believe, as I once did, in the “pure aesthetic”—that our expertise gives us an objectivity that allows us to identify good art, art that “works” and has impact. And generally we extrapolate from believing we know the truly beautiful that engages our hearts to purporting to know what will engage the hearts of our audience and our community.

It’s very Descartes. Very intro to philosophy freshman year: I think, therefore art is—driven by a notion of the singular individual’s sense of what’s beautiful. And this thinking is at the core of art making in the American theatre—a theatre driven by artistic directors who believe in their ability to identify a “pure aesthetic”—that which is clearly good art for all. Especially in our large theatres that take on the responsibility of representing the regional communities they reside in. The taste of one leader determines the offerings for an entire community. Taste: the best way to wield power in the arts.

I like it.

I don’t like it.

You can’t argue with the all-powerful I.

These decisions when made at an aesthetic distance are artistic choices made from the vantage point of power with more emphasis on form than on function. By that I mean the scenario goes, an artistic director picks the plays for the season then the artistic and marketing staff think about how the play will be useful to the community. Form precedes function. And the picking of the season is generally about a love affair—we watch at first with an eye toward what we deem to be formally beautiful, we aren’t thinking about a piece of art’s usefulness, how it might literally feed a hungry person, but rather we’re watching with an eye toward falling in love.

Artistic decision makers will say straight up that they choose what to produce or present based on “falling in love”

From Outrageous Fortune: the Life and Times of the New American Play:

There aren’t that many plays where that kind of love affair actually happens between an artistic director or whoever gets to make those choices, and the work. When it does happen, almost every other consideration becomes moot.

And we know falling in love is anything but useful or practical. And though romantic indeed, this living at the altar of the pure aesthetic, the altar of the love affair between curator and object, has gone the way of my lime green Schwinn circa 1977.

And the revelation and the revolution about the pure aesthetic and those who are clinging to it tightly…well the pure aesthetic is DEAD! Yes DEAD. I don’t care what you like or love anymore, and your form is dead to my function.

Your pure aesthetic can’t blow my head off. In other words there’s a good chance I’m not going to love what you love, your pure aesthetic will be like me on a stationary bicycle, dying a slow death. If self-propulsion doesn’t take me anywhere, why go to all that effort to ride in the first place? I’m not going to theatre that doesn’t propel me into something real.

So the new artistic mission?

Get out of the way.

And honestly, if you’re a curatorial type, quit believing in yourself so much. Whether as an artistic director, chief curator, or thought leader, your thoughts and passions and love will likely lead you to some place you find comfortable. I mean really, how many of you want to stop what we’re doing right now and pump out thirty miles with me on a bike? No really, raise your hand? So those of you with hands up are my tribe, but look at how many of you don’t love what I love.

Lester Bangs again:

I long ago gave up on giving the other fellow’s taste the benefit of the doubt. It led me to too many shitty, phony albums rhapsodized over by the influential sycophants serving as rock journalists…

The pure aesthetic has created a monoculture called the American theatre—two act dramatic realism by white playwrights with white actors watched by white audiences with a talkback after the show thrown in for anybody still awake.

The pure aesthetic is death to diversity of thought, image, performance, practice.

Believing in the pure aesthetic is like believing that a market economy is the one and only economy. And we are marketing in an economy of the pure aesthetic and the result: theatre isn’t for everyone; it’s for those with a solid standing in that market economy.

Economist Joseph Stiglitz in his book The Price of Inequality makes an important point about who is at the top of the economic food chain…it’s not inventors and scientists and academics but rather the bulk of those at the top are geniuses in business, and that genius is focused on a singular individual getting ahead of everyone else financially:

More than a small part of their genius resides in devising better ways of exploiting market power… and in many ways ensuring that politics works for them rather than for society more generally.

And our not-for-profit art institutions have taken this business of exploiting the market quite seriously. And the result is a lot of assets stored behind big glass buildings, locked in lock boxes of endowments, and unavailable to the artists who make the work, and the communities who live around all of those assets. And not-for-profit theatre is big and profitable business if you know how to exploit the market and convince your corporate board to work with you in that endeavor.

And the pure aesthetic and the pure market economy walk together hand in hand with the curators best able to join the two making more than the president of the United States.

Now I’m going to suggest that we need a new infrastructure, a new highway for the arts. In my world this is a highway of bike lanes, more affordable transportation, open to anyone interested in self-propulsion—in being involved in the high of imagining their hearts and lungs in sync with their creative lives.

Stiglitz argues in fixing our economy we must have new architects. He says, “we shouldn’t have expected the architects of the system that has not been working to rebuild the system to make it work, and especially work for most citizens—and they didn’t.” Will those currently driving their BMWs to the parking lot of their not-for-profit really be willing to trade it in for a bike?

Three years ago I had an idea for an online journal for the theatre. I still believed in the pure aesthetic then. My hope was to make a kind of mini New Yorker for the theatre, and to be its primary architect. I knew I didn’t want to add to the plethora of personal blogs out there, I truly didn’t think I had something unique enough to say to warrant that. But I desperately wanted more dialogue and rigorous thinking in our profession. I wanted it to be hip and well-designed. I’ve always had a thing for Allen Ginsberg and the Beats.

I started HowlRound because I personally wanted to unpack the question of aesthetics in our field. I had become enraged by the process for season selection—the ways plays were being chosen, safe choices, the same playwrights getting productions, a profound lack of diversity in voice and form. I had become enraged by so many artists left out of our institutions and off of our stages. We had become a corporate club for those with access, amply represented by those special donor rooms in some of our biggest theatres.

And I became enraged by how many people didn’t like what I like.

So I started a journal to keep my own heart beating. And the journal and the subsequent work with all of the communication platforms that make up HowlRound, pieces conceived by our team in consultation with that thing we call the crowd…that include much more than a journal…an interactive data map, a livestreaming television channel, and convenings and residencies—changed my worldview.

This is the beauty of rushing many-streamed complexity which when it finally grabs you can literally take your head away so that you’ll find yourself. . . it demands involvement on the part of the listener. You’ve got to pay attention to it, it’s not for the passive listener but shit, here I go sermonizing again.

I realized the role of the curator is deep listening. We must exchange our emphasis on watching and looking for active listening. The beauty of the rushing many-streamed complexity that Bangs talks about requires involvement by the largest data set we can imagine. We all want to be makers. And the biggest miscalculation of the not-for-profit arts institution in building its infrastructure is its belief that some people make things and some people just administer to that making. It’s been a failure of listening to why people get into to theatre in the first place.

Why are we so many of us obsessed with making things? Self-propulsion keeps the blood pumping through the heart.

Bourdieu argues that form and function separate how disparate classes experience culture. Those working paycheck to paycheck (not in the arts) seek experiences that are relevant to the day-to-day needs of living, of surviving. They gravitate to stories in whatever form that speak to their lives in a real and connected way. And those of us who make art, listening to the needs of the living, including the employees in our own offices, will help us to see the way forward to that new infrastructure. We will have to be within whispering distance to hear the nuance of the many streamed complexity.

Articles I love will sometimes get very few readers. Articles that have no impact on me, will get 10,000 readers. Huh? It’s happening again, others aren’t seeing things the way I do. But where that once caused rage, I now find it completely comforting.

The biggest shock of curating and editing a journal that is community sourced (meaning the ideas and content comes from the community that pitches them)? Articles I love will sometimes get very few readers. Articles that have no impact on me, will get 10,000 readers. Huh? It’s happening again, others aren’t seeing things the way I do. But where that once caused rage, I now find it completely comforting.

Individually identifying the pure aesthetic and trusting we’re right about that can no longer be our focus for creating moments of transcendence. Instead our radical curatorial gesture will be to listen—to believe that transcendence comes in the sweaty involvement of the crowd propelling itself—a crowd with a deeply different sense of beauty from our individual curatorial knowing. This upsets a history of understanding how to define beauty in art.

It was Elaine Scarry in her book On Beauty in the chapter “On Beauty and Being Wrong,” who helped me understand the importance of listening to other people’s sense of things. She spent most of a life time hating palm trees until one day she is on a balcony and the leaves of the palm are swaying around her for the very first time at eye level and suddenly she says, “It is everything I have always loved, fernlike, featherlike, fanlike, open—lustrously in love with air and light.” And in the moment of realizing how wrong she has been about the palm tree she wonders about all the other errors in beauty she has made, “How many?” she asks, “How many other errors lie like broken plates or flowers on the floor of my mind?” This is the question that forms the basis for each bike ride I take, as I try to stay present to the world in such close proximity to my lungs pumping and my heart beating.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

I don't pretend to be an expert on the theatrical world and it's desire to connect with it's audience but the neo-liberal language of engagement seems to be all the rage here. Phrases like "listening to the needs" of the community sound so positive but when does it become catering to the desires of the masses? And does your premise apply to the visual arts? Should artists make what people in a community want them to make?

I think your position is wrong on a couple important points.

"The taste of one leader determines the offerings for an entire community. Taste: the best way to wield power in the arts."

What you call pure aesthetics (and what I would say is good Art) is not solely driven by taste. It's driven by knowledge and expertise (experience) in one's field. Everyone has the right to their own taste but that right doesn't mean that what you like or desire is in fact any good. You can say you like Two Buck Chuck wine but most people that know about wine, that know what it is that makes good wine good, would say that your taste is not very good. And they would be right.

And I don't think that pure aesthetic is the "death to diversity of thought, image, performance, practice" nor does the "pure aesthetic and the pure market economy walk hand in hand." In fact just the opposite. Pure aesthetics, the real heart of what makes something Art, the true purpose of the aesthetic experience, has nothing to do with our capitalist market economy. John.F Kennedy started the seed that was to become the NEA because he rightly believed that art doesn't easily fit into our market economy and therefore it needed special assistance. Real art, good artistic practice and thinking, isn't a danger to diversity, gender, sexual orientation, or political progress. History shows us that it is pure Art, the pure aesthetic experience, that has time and time again change society for the better, pushing it forward to new awareness.

Our current art world certainly has problems. In the visual art world women and artists of color have been ignored, money has usurped the intrinsic value of art, we don't publicly support the arts any longer, the list goes on and on. But blaming the state of the Arts on "pure aesthetics" is not only wrong it's historically inaccurate.

Finally got around to reading this, and am sitting on the bus trying really hard not to whoop and pump my fists in the air. Thank you for this. So much yes.

Fascinated by the article and enlivened by the discourse in comments. In lieu of posting something unhelpfully long, I made a video outlining some of my thoughts.

Thank you for continuing to probe this difficult, adaptive conversation.

http://www.youtube.com/watc...

Fascinated by the article and enlivened by the discourse in comments. In lieu of posting something unhelpfully long, I made a video outlining some of my thoughts.

Thank you for continuing to probe this difficult, adaptive conversation.

http://www.youtube.com/edit...

One of the things I really believe about a thriving theatre of the future is that we need to not be like Descartes. In fact, it seems like we need to really speak to the embodiment that being in the same space and time with other live beings, both onstage and off, suggests. Your words: "Get out of the way" resonate for me. Sometimes it seems like we need to get out of the audience's way--in other words, we can create too much aesthetic distance for our audience's to really engage in a play.

I wonder what kinds of ideas you have about a theatre that really engages our sense of being embodied?

Almost as great to read as it was to hear you say these words at Seattle ArtsCrush. Sharing widely.

Margy thanks so much for your comment and for posting so widely! Much appreciated!

I LOVED listening and feeling this talk with you in Seattle last week!

Thank you so much for the opportunity to share it with you!

"I know it's a poem when the hair on my arms stands up," Emily Dickinson. And thank you Polly! for this essay.

Thank you Karen!

Thanks for this, Polly. It is exactly what I needed to hear today.

Thank you Tom for engaging with it, so appreciated!

There's a lot of good stuff here on the power of the curator and the current "non-profit market." I'm also left with questions.

"Will those currently driving their BMWs to the parking lot of their not-for-profit really be willing to trade it in for a bike?"

Isn't there room for both bikes and Beemers?

Do the architects of the new "non-aesthetic" need to dismantle standing infrastructure? What's wrong with diversity in practices? We (myself included) keep talking about the need/demand for a more participatory theatre experience, but the tens of thousands of repeat subscribers at my current theatre are legitimately happy with what they see. Are they all wrong? - And what would it mean for our organization, for our audience, to radically introduce divergent theatre next month/year? How would it affect the artists who are trained to do (and love doing) the type of work built into our programming and misson?

And moreover: isn't a manifesto calling for the end of the "pure aesthetic" itself its own aesthetic?

Hi Mark,

Thanks so much for engaging the piece and I appreciate your questions here. In terms of ...is there room for both bikes and Beemers, I guess I feel like it's hard to justify the Beemer mentality in the not-for-profit theater for me from an ethical standpoint when so many theater artists (successful ones!) don't have health insurance and haven't been to the dentist in a decade. How do we justify (and I'm speaking very particularly now to the huge infrastructure of some of our biggest artistic institutions) the cost of that infrastructure at the expense of the artist?

I'm actually not that interested in dismantling the existing infrastructure, and the people enjoying the current infrastructure aren't wrong, they are just a specific segment of the population....I'm asking more specifically who is theater for? And as we think about the next fifty years of not-for-profit theater, what infrastructure will we build and who will be invited to participate? Will we bring a specific not-for-profit ethic to that new infrastructure, or will it be simply driven by the market like the current one? Is theater for everyone (this is my very specific hope) or just for those who can pay for the ticket as the primary focus?

I think the future of our institutions will depend upon how they see themselves not as a business but as an instrument of civilization...that won't mean just offering a different aesthetic to audiences, it will me something much more significant I think, a turning upside down of the way we do business.

As to the the artists trained to operate in the existing system...again I would argue this is a small and specific segment. I'm confronted everyday with talented MFA trained artists with no place to take their creativity.

I don't think a manifesto calling for the end of a pure aesthetic is it's own aesthetic...I think we don't actually know what it means for the future of theater. Will a new infrastructure for the theater have its own problems and its own lifespan...I imagine the answer to that question is yes. Calling for change isn't calling for utopia.

Mark, I hope this is somewhat helpful and again I truly appreciate your questions!

Thank you Polly for your thorough and considerate response.

Hi Polly,

You must read the book Future Perfect by Steven Johnson. It is an account of how the hope of modern civilization lies in the decentralization of societal systems that we have come to depend on. Johnson proposes that we as a society are slowly evolving beyond regulated, mundane, cookie-cutter ways of exchanging resources and information (communication, food, transportation, etc.). Interestingly, what allows this to take place is the growing population of active, conscious, creative, inspired citizens that wish to participate in the exchange of information from a diverse array of communities. It is sick. And, given your article, I am sure you would enjoy the read. I always enjoy reading your posts.

Sam

HI Sam,

Thanks so much for this recommendation, will definitely take a look at the book!

A fascinating and important conversation.

But the larger reality is that the prevailing aesthetics of the art form will not change until the people making the art start to change.

And what will that take? It's a generational change that has to occur and it won't happen overnight.

Ultimately, theatre artists will make the kind of theatre that they like, not the kind that they "need" to make or the kind that they "should" be making. Most artists I know are collaborative, but they do not usually offer to cede control of their work to someone who doesn't share their aesthetic, let alone cede control of it to the public. Yet the public seems to be crying out for more ways to be involved and to be less passive in the process. Does that mean more "audience participation"? And what about folks who enjoy the art form, but DON'T want to participate?

So one of the only ways to change the "aesthetic' is to change who the artmakers are. For example, if the artmakers are largely of privileged backgrounds, those viewpoints will continue to be reflected in the art. But if we want people of more modest means to participate, how do we create space for people to devote time to pursuing that?

This is partly where arts education comes in. How/why are we training our next generation of theatre artists is a fundamental question that must be explored.

But there's also a financial component to this: as long as theatre costs more to produce than it is capable of bringing in, it will always depend 'on the kindness of strangers' (i.e.- wealthy donors, corporate/foundation grants, etc).

And if it is dependent on donations to survive, it will always be a province of the affluent...because non-wealthy people don't generally have much/any disposable income to contribute to charitable causes. And when the donors and funders control the resources, they also influence the product, whether they intend to or not.

So, as I see it, the challenge is two fold: 1) to bring new kinds of artists and viewpoints into the creation process and 2) to examine different models for funding and sustaining the art form.

I think you raise some great points here..and how we train the next generation will be a key to what our future looks like. And there's no doubt the current funding model is based in finding stakeholders of means...this has proven antithetical to opening our doors more widely.

I think though the future is less about audience participation in that more traditional sense and more about theater as a form of civic practice that involves and requires its community. Michael Rohd has written some good stuff on the site about that.

Thanks so much for engaging the piece with such a thoughtful response.

Thanks for your reply. I agree that Michael Rohd has offered some good stuff that could be indicative of possible directions to go.

I raised the issue of 'audience participation', however, because theatre-as-civic-practice requires a high degree of listening and collaboration....and often with individuals who are not trained theatre artists.

I personally think that's great....but I'm also not entirely sure that all (or even most) theatre artists would be willing to cede that much control over their process (and product).

Although I personally value civic engagement in my own work, I've spoken with plenty of others who do not. Their response (to paraphrase) is often something like this: "I do theatre because I have something specific I want to say," and/or "I have specific creative ideas I want to explore...and I don't want to dilute that by inviting other people to validate it or weigh in on it". ....OR "I want to work with professional theatre artists, not do 'community theatre'"

Perhaps not everyone in theatre is so dismissive of art-as-civic-engagement, but I think it's fair to say that this mindset exists out there.

Get out of the way. This the most important five-word instruction manual for anyone curating art.

Righteous!