Black Fringe

Something different happened at the twentieth anniversary of the New York International Fringe Festival, which ended earlier this week. The festival is best known for such campy spoofs as Urinetown, the 1999 Fringe show that is still the only one to transfer to Broadway to date. Yet this year, some two dozen Fringe shows were given the African-American “cultural tag,” a designation selected by the producers of each show, which usually describes its subject matter, but can also indicate the identity of its characters and/or of the theatre artists involved. There were more such shows by far this year than in any of the previous nineteen years of the Fringe. Moreover, some of these African-American plays and musicals were the most heralded of the 200 shows in the 2016 festival, five of them singled out for Fringe Overall Excellence Awards.

“I think we are experiencing a cultural shift, in which social media is encouraging bold stands on social and political issues, and artists are reflecting that,” Jonathan Louis Dent told me last year. Dent’s play, The Broken Record—one of the winners of the 2015 Overall Excellence awards for a play—offered a Groundhog Day-like riff on a police shooting of a black man, with the characters trying to relive the moment again and again so that it doesn’t end in tragedy. The success and visibility of Dent’s play last year could be seen as a kind of preview of what happened this year; it could also have helped encourage other African-American theatre artists to participate in the Fringe.

The breadth of these shows at this year’s New York Fringe underscores what should be obvious: There is a wealth of talent to stage a rich variety of stories concerning African-Americans, and a heterogeneous audience interested in hearing them.

Whatever the reason for the change, the presence of so much African-American theatre art at the Fringe this year seemed to affect the very tone of the festival

Violence

Some of the most acclaimed shows this year dealt with violence against black people.

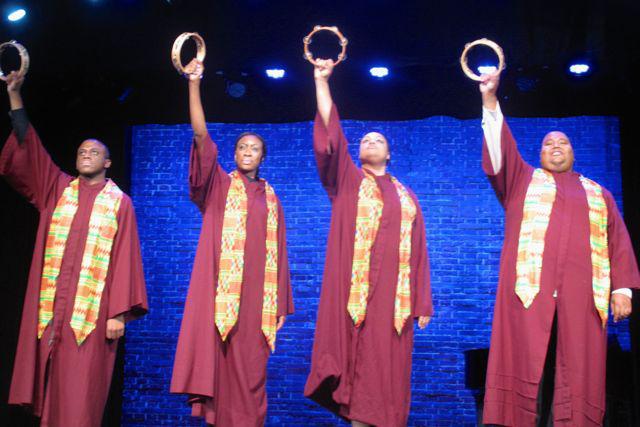

Mother Emanuel is set on June 17, 2015, the day that nine members of a Bible study group at the Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina were shot dead, by a young racist allegedly intent on starting a race war. But, while the play is uncommonly earnest for the Fringe, it is more of a celebration of the lives of the church members. The bulk of the ninety-minute show feels like a lively church service by a pastor who knows that music is the only way to keep the pews filled; the talented cast of four performs many rousing spirituals. There are also flashbacks in the lives of each of the characters, and a re-creation of President Obama’s moving eulogy, but a sign of the importance of music in the show is that Mother Emanuel was given the Overall Excellence award for a musical. It will be presented again as part of the Fringe Encore Series later this month.

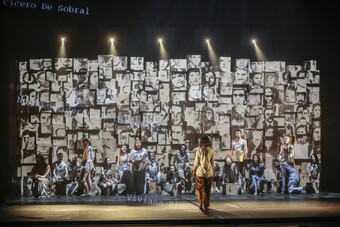

Black Magic was selected for one of the three Overall Excellence awards for a play. It too recounts the stories of murdered African-Americans; it too approaches the subject with as much joy as sorrow or outrage, and it too winds up a polished entertainment, with music and dance accompanying the poetic monologues. Black Magic is written and co-directed by Tony Jenkins, a senior at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, who considers it a “choreopoem,” a phrase coined by Ntozake Shange to describe her for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf. The dead black men in Black Magic are unnamed, with only a suggestion of biographical details.

Black and Blue also employs poetry to explore violence against African-Americans, but the spoken word poetry by Katherine George is interspersed with a more traditional narrative written by Kevin Demoan Edwards, which focuses on the relationship between a Black Lives Matter participant whose cousin was shot by a police officer, and a white cop. The playwright cleverly constructs a scenario by which the two are nearly forced to befriend one another—their wives are friends, nurses together at a local hospital, who insist that the two families socialize.

The other black Fringe shows dealt with violence include a revival of Cherry Jackson’s 1978 In the Master’s House There Are Many Mansions, in which friends catch up with one another in a funeral parlor after one was killed by police; and, more implicitly, Let the Devil Take the Hindmost, which touches on a range of issues, including a violent act in the past that embittered one of the central characters, leading her to poison her relationships with her family.

Biography

Several well-known African-American figures from the twentieth century were the subject of solo shows at this year’s Fringe.

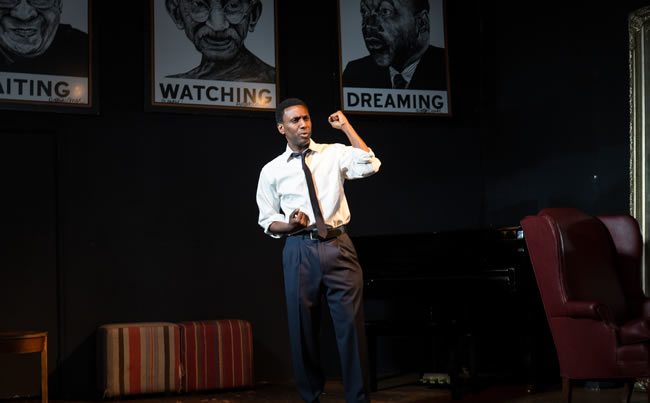

W.E.B. Du Bois: A Man for All Times effectively and efficiently offers highlights in the long life of the formidable public intellectual and uncompromising civil rights activist, who died in 1963 at the age of ninety-five. Written and directed by Alexa Kelly and performed by Brian Richardson, the play makes accessible the man who was the first African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University and the co-founder of the NAACP, and introduces some of his ideas such as “double consciousness,” wherein a black man is forced to see himself simultaneously both as he sees himself and as white Americans see him.

In Power! Stokely Carmichael, writer and performer Meshaune Labrone chooses to focus on a single moment in the life of the man best known as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, who is credited with popularizing the phrase “Black Power.” Here Carmichael gives a speech to demonstrators before the March on Fear in Mississippi in 1966, denouncing Martin Luther King Jr’s non-violence as a failed strategy. Labrone portrays other, unnamed characters who have gathered for that march, one of whom tells a gruesome tale of a nineteenth century lynching.

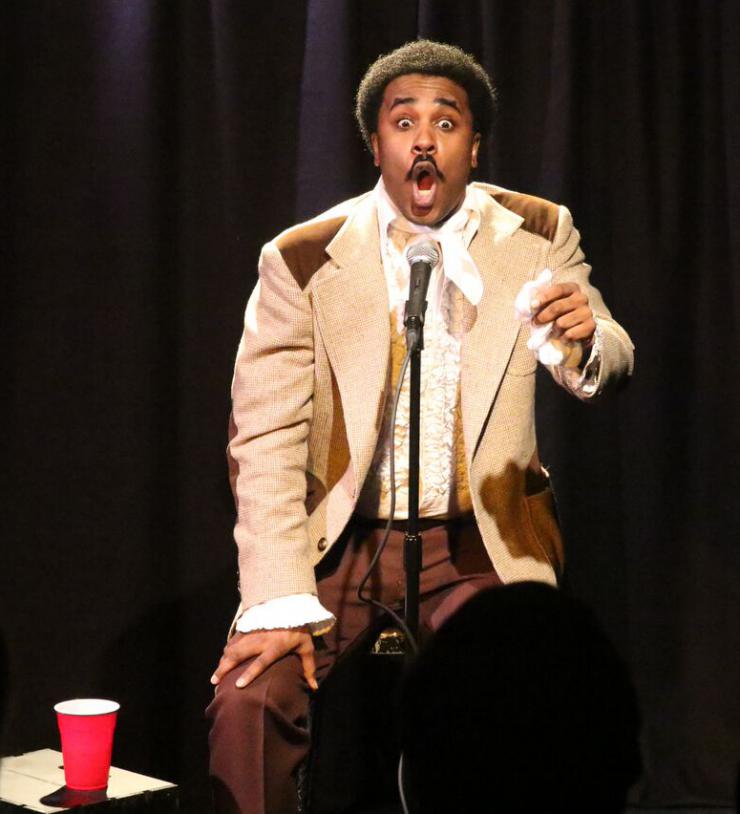

In Pryor Truth, Khalil Muhammad doesn’t even portray the comedian Richard Pryor; instead, he plays one of Pryor’s characters, Mudbone, who tells the story of Pryor’s life, and offer a taste of his bawdy and profane humor. It won an Overall Excellence award for solo performance.

The comedy about Richard Pryor drives home what shouldn’t have to be said: “African-American” is not necessarily synonymous with “serious social issue.” But there is urgency in the literally life-and-death issues that daily confront the black community, and so it makes sense that black theatre artists tend to reflect it. Still, other shows in the festival (that I didn’t see) included My White Wife, or So I Married a Black Man, a comedy about an interracial marriage; Everything Is Fine Until It’s Not, Doreen Oliver’s solo show about raising an autistic son; Dust to Dust, about five neighbors; Colorblind'd, a play about an African-American professor who casts a white girl as Rosa Parks over the sole black girl in the drama department. There was also a history play, a thriller, a “surreal love story,” and Red Devil Moon, a musical Inspired by Jean Toomer's modernist novel, Cane.

A New Kind of Silliness

Kevin R. Free, who won an Overall Excellence award for playwriting, was most successful (of the shows I saw) in synthesizing the traditional Fringe silliness with seriousness. Night of the Living N Word takes place in an old plantation off the coast of Georgia, where Barbra, the daughter who rejected the Confederate values of her family and married a black man, is returning home to celebrate the birthday of her biracial teenage son. Barbra has banned the N-word from the household, and from her hearing, and resorts to some over-the-top punishments for anybody who defies her. This implies that there is a straightforward story, but Free is a trickster, springing surprises and reversals into a convoluted plot from sketch comedy to campy horror movie spoof to black comedy. The cartoonish feel is assisted by the cardboard cut-out props and sets. However, Free’s aim is not just to surprise and amuse us. Night of the Living N Word makes serious points about the differing views of black and white America towards race. Free sees his play (as he commented to me) as “a funhouse mirror version of the world in which we live.”

The breadth of these shows at this year’s New York Fringe underscores what should be obvious: There is a wealth of talent to stage a rich variety of stories concerning African-Americans, and a heterogeneous audience interested in hearing them.

***

Jonathan Mandell’s Newcrit piece usually appears the first Thursday of each month. See his previous pieces here.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here