When entering new communities, school-based teaching-artists work hard to establish cultures of trust. In October of 2023, the former artistic director of a theatre organization invited me to join a team of incredibly talented Black and Brown theatremakers to facilitate a one-week educational theatre residency at a St. John, USVI (STJ) school. Coming to STJ as a United States citizen, I knew how my presence reinforced a long legacy of settler-colonizing still impacting the STJ. STJ, the indigenous home to the Kalinago people and a vibrant ecosystem, experienced violent atrocities due to acts of genocide, a history of enslavement, and Danish and United States colonization. This place was not my home, and as a guest in this community working against oppression, it was my responsibility to find a pedagogical framework that respected my students’ communal epistemologies. However, some of the practices in this school, and across many United States schools, are deeply rooted in settler colonial and plantation logics.

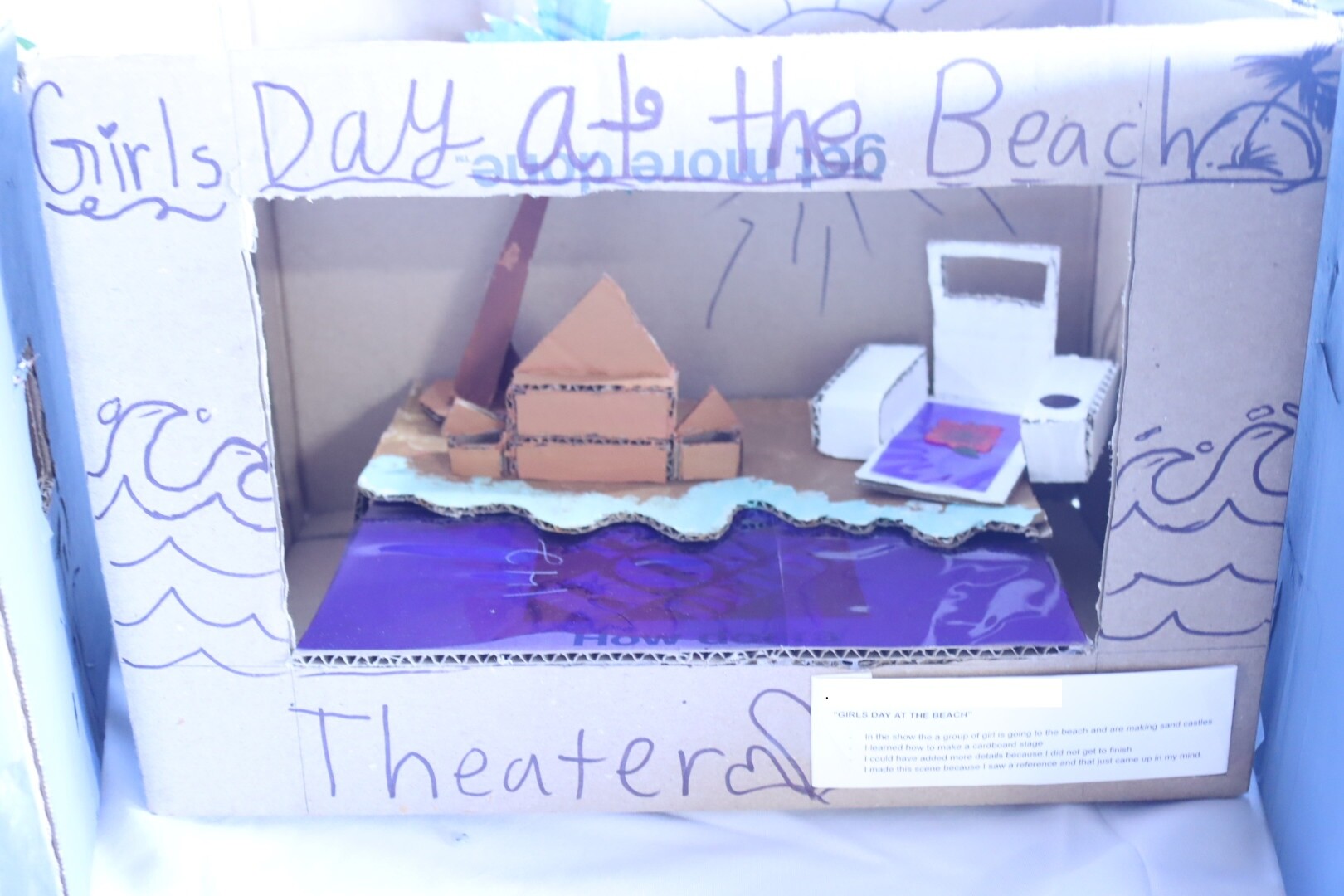

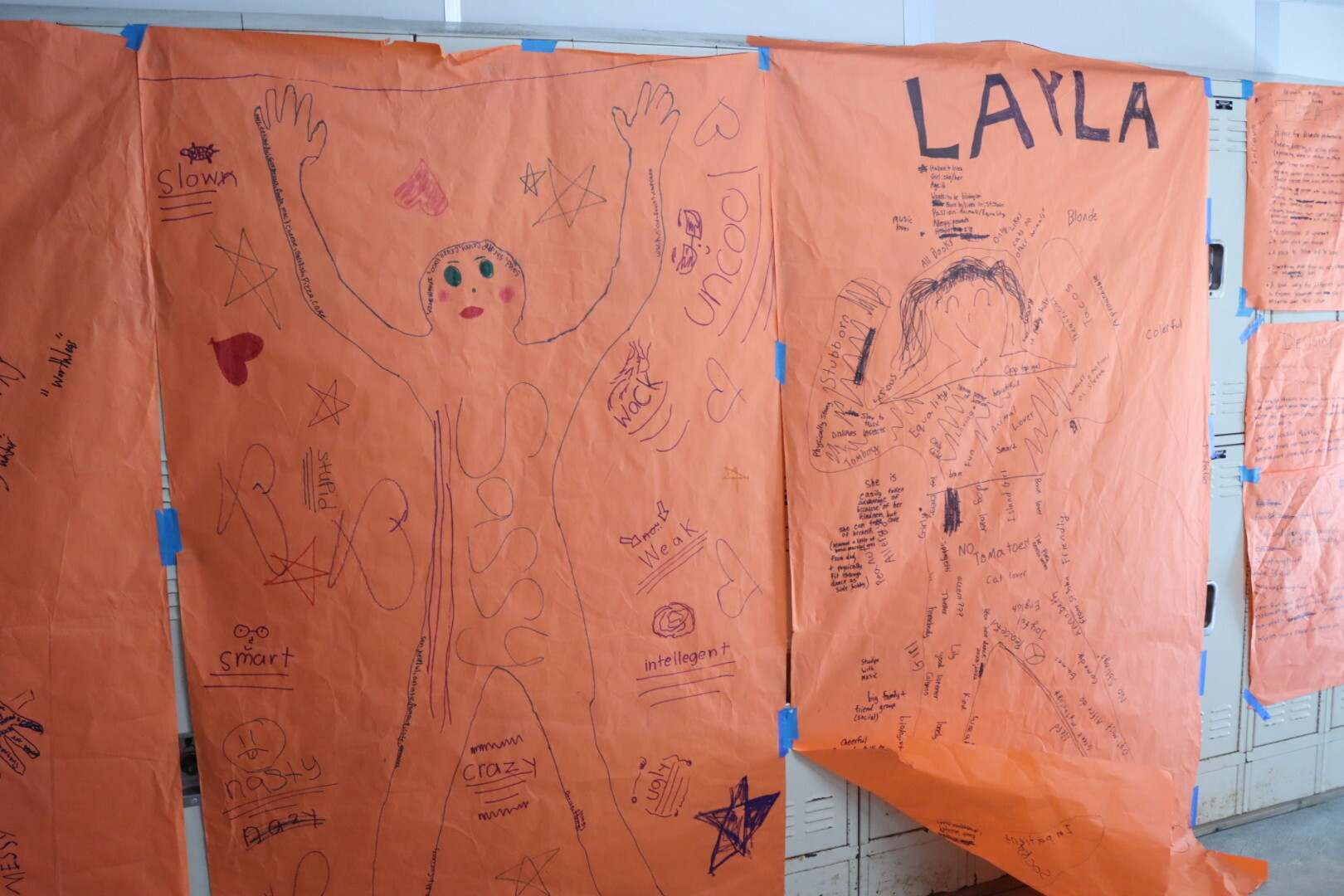

Articulated by Savannah Shange, the notion of "plantation logics" within the American school system influences behavioral and classroom management practices, aiming to keep students "in line" through racialized, gendered, and adultist methods that strip children of their humanity. In these learning environments, children face heightened surveillance, a lack of agency in decision-making, disciplinary measures shaped by their intersectional identities, and are often perceived as having limited prospects for their future. As teaching-artists, we felt like the school expected us to uphold practices that misaligned with our teaching values. Upon arrival, the school had predetermined acting and technical "tracks" for students, hesitating to grant some the autonomy to choose their preferred path. Furthermore, we were instructed to monitor behaviorally challenging students, particularly Black students and girls. In our devised theatre work, we aimed to subvert this power dynamic, encouraging students to choose how they wanted to participate. This fundamental shift in pedagogy positioned us, the visiting teaching-artists, as outsiders attempting to reshape the school's culture temporarily.

Conversely, we also had to be mindful of avoiding the reinforcement of white progressivism logics. Art organizations sometimes approach their work with the outlook of providing an empowering, life-altering service to historically dispossessed communities, often viewing them through a scarcity mindset. Perceiving the school and community as lacking moral or cultural capital can foster a dynamic of white saviorism, reinforcing settler colonial ideologies. Deliberately, we prioritized sourcing materials, costumes, tools, and props from students and community stores. Following suit, it was crucial for me to integrate pedagogical strategies inspired by the island into my teaching methods.

I found a new pedagogical practice in Leanne Betasamosake Simpson's book As We Have Always Done, where she offers readers a Nishnaabeg cultural understanding of "Land as Pedagogy." First introduced to this concept by Prof. siri gurudev, PhD, I considered Simpson's "Land as Pedagogy" theory to inform and reflect on how I build trust with school community members while devising theatre with youth in STJ. In doing so, I viewed Cinnamon Bay, a beach in STJ, as a teacher whose wisdom and ecosystems inform my teaching-artistry practice by considering place, time, and social context.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here