The Dramaturgy of Gender

How Audience Expectations Shape Storytelling

The word of the hour is parity. Last year, The Kilroys launched The List of plays by woman writers, and Jeanine Tesori reminded us that when it comes to artistic aspirations, girls “have to see it to be it.” Then, this October, Jennifer Lawrence fired a high-profile salvo in the war against the Hollywood wage gap. From the point of view of actors and audiences, the theory at work here is a kind of trickled-down equality. If writers and artistic decision-makers are women, that will naturally result in more roles for women; thus, more opportunities for the theatre’s majority-female audiences to see someone who looks more like them onstage.

Even the most cursory look at the types of female roles on display on our biggest stages suggests that increasing opportunities for actresses won’t solve the equality problem in any sense, except the numerical—not until we take a closer look at the kinds of roles that women are being offered.

But is evening out the numbers enough? Even the most cursory look at the types of female roles on display on our biggest stages suggests that increasing opportunities for actresses won’t solve the equality problem in any sense, except the numerical—not until we take a closer look at the kinds of roles that women are being offered.

Web series like Lady Parts highlight some of the most extreme examples of sexist, stereotypical, and just plain unimaginative options for actresses. But I became interested in exploring the subtler biases that audiences and directors might exhibit towards female characters. In her article for American Theatre, Joy Meads, literary manager at Centre Theatre Group, uses neuroscience to explore what a remarkably large effect subconscious bias has on our decision-making processes, and how that relates to the continued failure to achieve radical diversity in the theatre. Not long after that article was published, Vicky Featherstone, artistic director of the Royal Court Theatre in London, expressed recognizing her own internalized biases in an interview. She argued that the dearth of iconic female roles comes down to audiences’ and critics’ (and, implicitly, artistic directors’) unwillingness to accept complex female characters.

Although neither of these articles had been published while writing my MFA thesis, I undertook an experiment to examine whether these biases, which I intuitively believed in, existed in a way that could be indicated more systematically. It was emphatically not a scientific study, but it produced some very compelling patterns, which suggest that the battle to level the playing field for women onstage must look to more than just numbers.

A quick note about gender before we proceed: in the project itself, and in this description of it, I deal with gender as a binary. This is not because I believe this is true, but because “male” and “female” are the terms under which the majority of our cultural expectations about gender have been formed, and it’s these expectations that the project was designed to investigate. I fully recognize that in doing so, a huge aspect of this conversation relating to trans, gender queer, and gender-nonconforming actors and characters are neglected—there simply wasn’t time within the scope of the project to do the question justice. I hope someone else will! I also hope that probing at the confines of the binary in this way can bring us a few steps closer to tearing them down.

The experiment looked like this: I wrote a one act that was performed by a rotating cast, with a man and a woman trading off performing each role. After each performance, the audience filled out a survey that was designed to explore how their reactions to and understandings of the male and female versions of each character differed.

Of course this is not a perfect experiment in a scientific sense. Two actors will never be able to perform exactly the same way—even the same actor can’t guarantee an identical performance every night. But we tried our best, and even given this caveat, some interesting results emerged. These are the patterns I found.

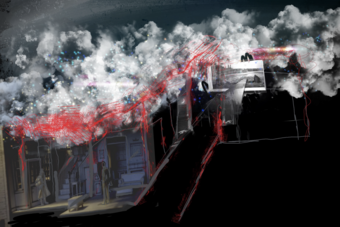

by Theatro Teera.

Two Against One

Some of the most strikingly different responses were generated when one of the characters was either the only man or the only woman in the group. Audiences revealed subtle but distinct expectations about how men and women were meant to behave towards one another.

For example, when the most aggressive and outspoken character was a woman pitted against two men, audiences viewed her more positively than usual, but viewed the male character, who was trying to act as a mediator, dramatically more negatively. He was described as being “cowardly” and “self-interested”—words that suggest that audiences expected him to rise to the female character’s defense.

The opposite could be seen when this same outspoken character was man opposed to two women. Positive perceptions took a steep nosedive, and he was accused of being too abrasive, too aggressive, and too forceful. In short, audiences overall displayed a protective streak towards the female characters, and reacted very negatively to scenarios in which they seemed to be bullied by men.

This is interesting because the only thing that changed from one scene to the other was the gender of the characters. The situation itself was no more or less disrespectful, or threatening than before (and it’s worth noting that the scene did not involve any physical violence).

On the other hand, when the mediator character was the only man between two women, the audience viewed him dramatically more positively than other situations, and the other two characters much more negatively. I believe that having a male mediator of a female dispute made audiences perceive the women’s problems as more immature and unimportant. The mediator’s gender combined with his peacemaking position may have granted him increased authority in the eyes of the audience, leading them to tilt their understanding of the conflict in favor of his being “right” and the women being “wrong.” When the play was an argument between two women, with a man in the middle trying to make peace, the male voice became privileged in the ears of the audience, and they took the mediator’s position that the other characters’ argument was ultimately pointless and immature.

This points to a much more profound ability to change the meaning of the play. The crux of the play’s moral dilemma—who was right and who was wrong, and to what degree—completely shifted, becoming a question not of the contents of the argument, but whether it should be happening at all.

courtesy of Hailey Bachrach.

What’s My Motivation?

Audiences also registered shifting understandings of why characters behaved the way they did. Female characters were dramatically more likely to receive descriptions that focused on the difficulty of their circumstances, words that implied their actions derived from a sense of turmoil (terms like conflicted, lost, stressed, trapped, exasperated, and exhausted appeared, among others). Their male counterparts often had their actions couched in more overall negative terms—angry, aggressive, and reckless—but these actions were linked to a kind of moral certainty: strong moral compass and honest. This suggested to me a desire to root female characters’ unpleasant behavior in her circumstances and thereby excuse or justify it, whereas male characters were assumed to be acting from inner conviction, however misguided.

The aggressive and outspoken character listed above was, when played by an actress, particularly victim to the stereotype that women are driven by their uncontrollable emotions. Though both versions were described as impulsive, only the female version was emotional, passionate, and impatient.

Similarly, the female version of the mediator character was frequently described with words like annoyed, exhausted, and impatient. The audiences saw her as much more worn down by the situation than her male counterpart. In general, she was viewed as markedly passive, like a witness to the action rather than a participant. Like we saw above, when the male version was seen as passive, the audience reacted very negatively.

This mediator is a character that is silent for long sections of the play, and these divergent responses strongly suggest that audiences were interpreting this silence very differently. In general, audiences viewed the male version’s role in the scene as more active and self-interested. I say “self-interested” to highlight what I think is at the heart of this difference: the character in question exists to push the scene forward between two other characters, or s/he has a stake in the scene him/herself. Responses suggest that the female version was seen as fulfilling the former role, while the male version occupied the latter.

I think this points to a huge gulf between expectations for male and female characters that exists both socially and dramaturgically. The idea of woman as helpmeet who devotes herself to her husband and children is all too familiar. Although huge strides have been made in terms of social opportunity for women, there is still a strong and insidious strain of expectation that women devote their lives to another person. This in turn affects dramaturgical expectations. Audiences seemingly could not accept the idea of this male character having nothing to do, and so inferred interior motivations and subtle kinds of activity. They were much more willing, however, to believe that the female version existed only when she was needed and receded when she was not.

This is the product of a lifetime of seeing female characters whose role is exactly that: step in when the (usually male) main characters require it, then absent yourself, get kidnapped, or be without will or agency when the final confrontation comes. It is a place we are very accustomed to seeing women inhabit in stories, and therefore audiences easily assume that this female character is another example of it. For men, it is much more unfamiliar, and audiences therefore assume that the male version is not occupying such a place of passivity (and react very strongly and negatively when they think that he is). This is one of the outcomes I find most interesting because it has such significant implications for theatremakers.

As the writer of the one act in question, I know that I intended the character’s role to look more like the male version: that his silence was active, and his investment in the scene was as high as anyone else’s. But given identical text, blocking, and actor motivations, the audience still mentally forced the female version into a traditional and stereotypically passive role. It would be ridiculous to think that because audiences want to assume women are passive, we must forbid this by writing and performing only loud, assertive women. There are quiet, passive women in the world, just as there are quiet, passive men. But quietness does not equate to lack of interiority or investment. This underlines why theatre artists must be aware of when they are treading alongside a stereotype, and how willing audiences are to slip over that line in their imaginations—even when the play might be trying to tell them otherwise.

Almost the opposite situation can be seen in the different responses to the most timid and awkward character, an artist. While this was certainly the most negatively perceived character overall, audiences were much more willing to acknowledge the female version’s positive qualities like her intelligence and creativity, while they dismissed the male version as needy and awkward. In other words, they were more willing to read nuance into the female version’s actions. While her descriptions reflect a clash between her talent and her fear, the male version paints the picture of an almost entirely pathetic, useless individual.

Though it has the opposite outcome of the case above, I think it is actually rooted in similar expectations of female passivity and dependence contrasted with male activity and independence, and audience members’ familiarity, or unfamiliarity, with characters of those types. In this case, however, the benefit runs in the opposite direction. Particularly these days, the bright but awkward, insecure female character is a recognizable type—just look at almost any romantic comedy. While this persona certainly exists for men, it almost always seems to be a purely comic type, the insecurities mined for their humor rather than the pained awkwardness of this character. Perhaps we may assume that the reason this type is funny is because of its failure to live up to masculine ideals of confidence and strength. Thus, when the humor is taken away, one is left just with an apparent failure of a man. And it’s a failure of imagination, too: audiences don’t know how to recognize this person, and so cannot supply the necessary, unspoken details.

No one will be surprised to hear that the word ‘bitch’ was only applied to a female character. Perhaps it’s also unsurprising that the word ‘coward’ was only applied to a male character.

“Bitch” and “Coward”

No one will be surprised to hear that the word “bitch” was only applied to a female character. Perhaps it’s also unsurprising that the word “coward” was only applied to a male character. Women, who do not labor under the same cultural expectations of bravery and physical valor, are not branded with cowardice, especially if women are perceived as failing to live up to them.

But there’s another set of female-only descriptions that I find more difficult to explain. These were independent, “speaks her mind,” and strong. All of them are, without question, positive descriptions, and probably more positive than almost any of the words assigned to this character’s male counterpart. However, the fact that the female version was singled out for these particular praises and the male was not suggests that the praise may not be as unequivocal as it seems. There is something about these word choices that suggest the respondents found them (almost certainly unconsciously) to be unusual, and therefore worthy of note. Independence, strength, and outspokenness could be used to describe the male version, but apparently audience members did not find them to be notable traits, or defining characteristics. But multiple audience members highlighted these traits across multiple performances for the female version—implying, perhaps, that while they are remarkable qualities in a woman, they are taken for granted in a man.

When the audience members for these configurations were asked to describe the play literally and thematically, they all roughly hit on the same ideas. But the surveys reveal that in fact, their perceptions of the intention, power, and responsibility of the characters differed greatly even within a shared dramatic framework. I wouldn’t say that any is right or wrong—each has its own interesting and less interesting elements. But if this were a more traditional play production process, there would surely be a story that the creative team and I were most interested in telling. The variations between the groups reveal the level of attention a dramaturg, director, writer, or all of them must pay to the preconceived notions about gender relations that audience members bring with them into a play.

Using this information, could we put together performances that actively work against the preconceptions revealed by the surveys? Would audiences ever allow themselves to feel sympathetic towards a male character fighting against two women, or negatively disposed towards a female character fighting against two men? I think it is fairly clear that we cannot just change the bodies that are enacting stories onstage; we must pay close attention to how we can change the kinds of stories audiences (and theatre artists, too) have been conditioned to see.

If the theatre is a place where audiences can be successfully called upon to imagine that there is an ocean onstage, a doll is really a baby, or that absolutely no one can tell those twins apart, is it really possible that we cannot make audiences imagine that men and women are not as easily defined as they believe?

Summing Up

The discrepancies between the characters that emerged from this experiment are not, I think, the effects of innate sexism or bigotry. But I think there has been a failure of imagination, a failure to look for, understand, or accept characters as flawed and complex humans rather than weighing them against an accepted and expected type. If the theatre is a place where audiences can be successfully called upon to imagine that there is an ocean onstage, a doll is really a baby, or that absolutely no one can tell those twins apart, is it really possible that we cannot make audiences imagine that men and women are not as easily defined as they believe?

My conclusion is not that everyone is irredeemably subconsciously sexist, or those centuries of ingrained gender stereotypes have left us incapable of breaking free of prejudice. Instead, theatre artists need to seize control of this aspect of characterization and storytelling, rather than allowing stereotypes and expectations to carry the day by default. By doing so, we can begin filling in the gaps in onstage gender parity, not just in terms of literal numbers, but also in the range and depth of female characters available.

Selected Further Reading

The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media researches depictions of female characters in children’s media and advocates for more positive and responsible representation.

Emily Glassberg Sands’s 2009 thesis investigates producer bias when evaluating plays by female-identified playwrights.

Jill Dolan discusses the effect of gendered bias on our collective formation of the “canon” of classic plays (among other issues) in The Feminist Spectator as Critic.

Comments

The article is just the start of the conversation—we want to know what you think about this subject, too! HowlRound is a space for knowledge-sharing, and we welcome spirited, thoughtful, and on-topic dialogue. Find our full comments policy here

Hailey,

Thank you for this contribution to HowlRound. I found it fascinating, valuable, important, and significant for all individuals involved in the craft of theatre making: playwrights, directors, actors, producers etc. I must admit being a little surprised and disappointed that I didn't see more comments posted, as the topic is certainly timely, and the article was so well written. I will keep these insights and suggestions in mind for my own personal future endeavors with writing and directing. Thanks again.

I have seen so much of this type of commentary in my plays with "strong" female characters. In some cases, audience members don't buy the female's action, where they would easily "buy" it if the character were a man. In one play where a woman commits a violent act, she is deemed "crazy" rather than violent or aggressive. It's disturbing that an entire play as potentially not believable because a woman is acting against type.

I would see such an audience reaction as a complete failure of the actor and director to find the authentic rationale that drives the character — more a case of inadequate, if not lazy preparation on their part rather than of any fault of the playwright.

But that's precisely what we discovered was not the case with this experiment: given the exact same preparation and process by the director and both actors, audiences were still unwilling to accept certain traits and circumstances if they perceived them as "inappropriate" for the character's gender.

What do you mean by "exact same preparation and process"?